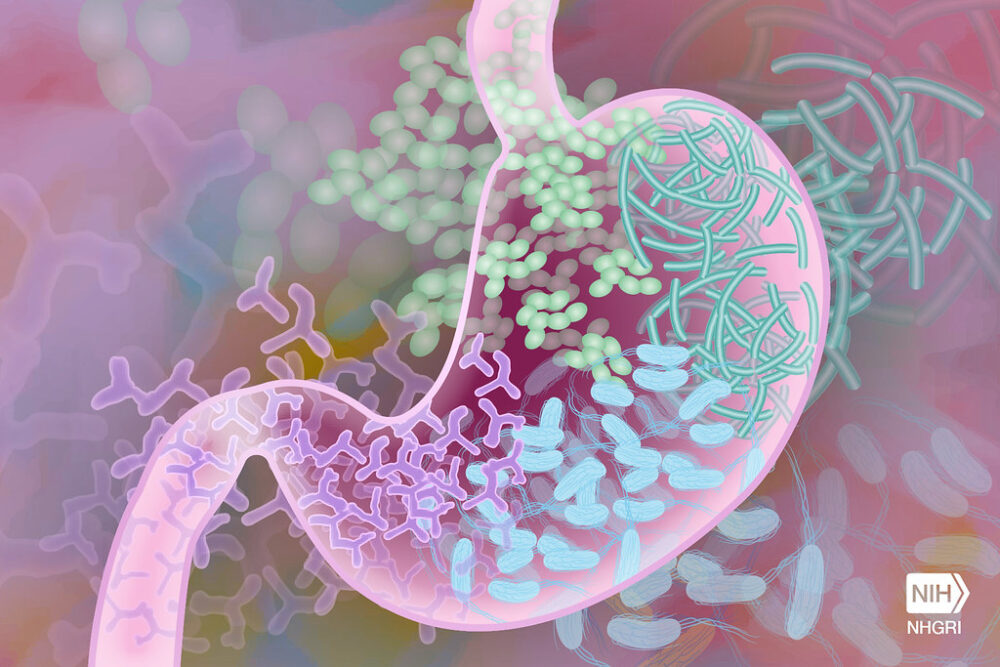

Next time you feel lonely during this time of social isolation, just remember you always have 100 trillion friends. Why? Because you aren’t really alone. As you read this, there are 100 trillion microorganisms who call your digestive system home and are dedicated to keeping you healthy. Contrary to popular belief, not all strains of bacteria cause illnesses like food poisoning or Salmonellosis (Salmonella poisoning). In fact, strains like Lacillobacillus and Bifidobacterium (commonly known as probiotics) have been linked to health benefits for a range of conditions like atopic dermatitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and hypercholesterolemia.

A recent field of study demonstrates that a lack of diversity in the gut microbiome may cause health conditions, namely neurological ones. In 2006, Jane Foster and her team at McMaster University made a pioneering discovery in this area. When Foster compared mice with a healthy collection of gut microorganisms to those who lacked them, she noted that the mice seemed less anxious than their healthy counterparts. This initial finding began a flood of research regarding how the connection between the gut and the brain is controlled by the gut microbiome. Through studies in mice and the beginnings of human studies, scientists have now determined possible connections between the presence of certain gut microbes to neurological conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Therapies to modify the microbiome could potentially prevent or stop the progression of certain diseases with some initial testing in human clinical trials already underway.

Through studies in mice and the beginnings of human studies, scientists have now determined possible connections between the presence of certain gut microbes to neurological conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

Gloria Choi, a neuroscientist at MIT, and Jun Huh, an immunologist at Harvard Medical School, have made eye-opening discoveries regarding the connection between ASD and the gut microbiome. In past work, a greater chance of ASD diagnosis has been linked to an infection during pregnancy. Choi and Huh wanted to determine the cause of this correlation, so they triggered the mice’s immune response to act as if their bodies were exposed to an infection. They found that a type of bacteria called filamentous bacteria affected T-17 helper cells, which are essential for the adaptive immune response. The cells became overactive and produced IL-17, a molecule important for cell signaling. These IL-17 molecules moved through the mother’s placenta and into the brains of the pups by binding to a neural receptor, resulting in neuroatypical activity in the newborns. To see if removing these filamentous bacteria would make a difference in newborn health, the researchers targeted the bacteria with an antibiotic and then triggered a similar infection in the mice. Surprisingly, the T-17 helper cells didn’t produce IL-17, and the pups exhibited neurotypical traits. Choi and Hun are currently working to determine if SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) can cause changes in the maternal gut microbiome, increasing the chance of neurological conditions like ASD.

Recent research has determined that modifying the gut microbiome can significantly impact the progression of neurological diseases such as ALS. Eran Elinav, a scientist at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science found stark differences in the progression of ALS from one patient to another and wondered whether the microbiome could explain such differences. In order to test his theory, Elinav worked with ALS mice models and found that if he cleared a mouse’s gut of its microbiome, ALS would progress more rapidly than in a mouse with a normal microbiome. In determining a supplement for the mice lacking a microbiome, Elinav sought out which products of bacteria, also known as bacterial metabolites, came from mice with a normal microbiome. Elinav and his team analyzed vitamin B3 (nicotinamide) and administered supplements to the mice, finding that the vitamin B3 molecules travelled to their brains and led to slower development of ALS symptoms. Vitamin B3 is currently being offered as a supplement to ALS patients in a clinical trial, and Elinav and his team hope to further investigate more bacterial metabolites for different neurological conditions in the future.

The future of personalized medicine is changing and alternative treatment options for conditions that were death sentences in previous generations are gradually becoming a reality.

The future of personalized medicine is changing and alternative treatment options for conditions that were death sentences in previous generations are gradually becoming a reality. With the ability to modify the gut microbiome, there is a possibility that genetics will play less of a role in determining the outcomes of one’s health. As a result, patients will have more ownership of their health, placing the burden of responsibility on themselves, which is powerful, but also a little scary to think about.

Image Source: Flickr