The human body is a grand hotel for trillions of microbes. Microbes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, collectively known as the gut microbiota, partake in a mutualistic relationship with humans by assisting in functions that maintain human health. However, the gut microbiota can be affected by factors such as diet, genetics, antibiotics, and probiotics, to name a few. This causes gut dysbiosis, or a disruption of the symbiosis between the microbes and their human host.

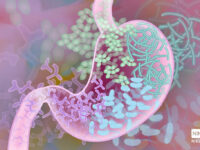

Dysbiosis in the human gut microbiota has been linked to changes in mood and mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. The gut microbiome has the ability to produce or stimulate the production of neurotransmitters, which are important to emotions and behavior. In fact, 90 percent of serotonin in the human body is produced in the gut. These neurotransmitters may in turn influence the central neurotransmitters in the brain through what is known as the brain-gut-microbiota axis (gut-brain axis). The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system between the enteric nervous system, which is the nervous system of the GI tract, and the central nervous system, which is made up of the brain and spinal cord. If the composition of the gut microbiota is altered, then there could be an effect on activity in the brain, which can manifest as alterations in one’s emotional state.

The gut microbiome has the ability to produce or stimulate the production of neurotransmitters, which are important to emotions and behavior.

An example of a possible correlation between the gut microbiota and mood can be seen in a study involving the transplant of gut bacteria. In the study, scientists separated rats into groups: rats that cope better with social stress (resilient), rats that do not cope as well to social stress (vulnerable), a non-stressed control group (control group), and a placebo group. Within the vulnerable rats, the scientists found that specific bacteria, such as Clostridia, were present in higher amounts than in the other groups. The microbiota of the stressed rats were moved by fecal transplantation to new groups of rats that had not been stressed. The results showed that the group with the fecal transplant from the vulnerable rats exhibited signs of depressive-like behaviors while the behaviors of the other groups did not change.

Although studies such as the one mentioned show promising results supporting the relationship between gut bacteria and mood, there is much research to be done before the relationship can be solidified as causation rather than correlation. If causal relationships are established, the treatment for psychiatric disorders could take a new and exciting turn.

Frontiers in Genetics (2019). DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00098

Molecular Psychiatry (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-019-0380-x