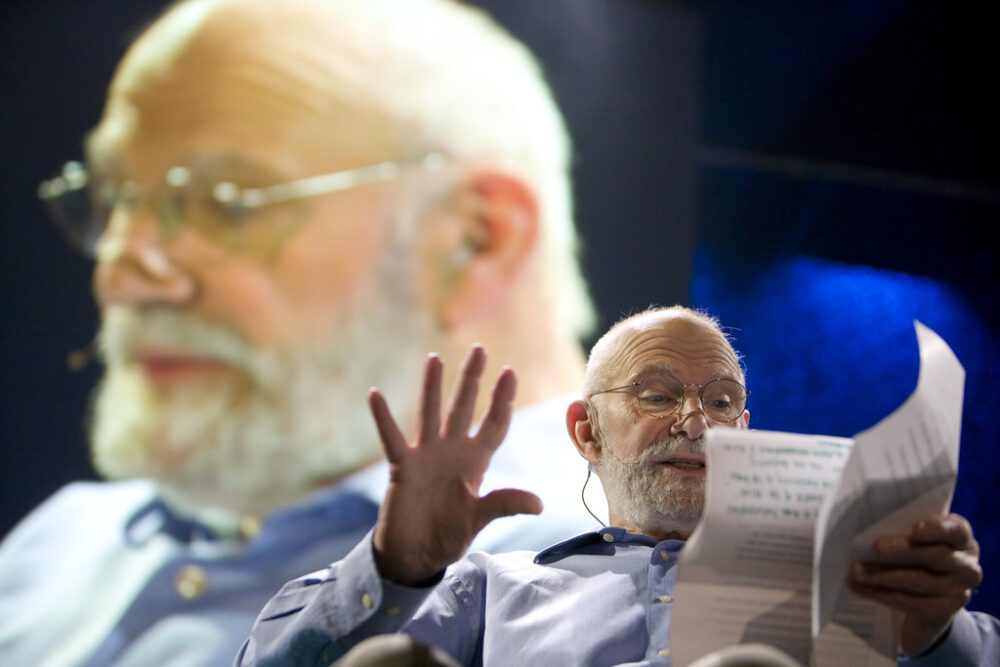

In the 1990s, the US government heavily funded neuroscience research and sponsored numerous programs to educate members of Congress and the public about the wonders of the brain. But years before this “decade of the brain”, the writings of a man named Oliver Sacks helped introduce the world to the complexities of neurology and cognition.

Dr. Oliver Sacks was born in 1933 in London, England to Samuel Sacks, a general practitioner, and Muriel Elsie Landau, one of the first female surgeons in England. Sacks’ interest in science was fueled early, and by the age of 10, he had immersed himself in his basement chemistry lab. He eventually came to share his parents’ passion for medicine, receiving his medical degree from Oxford University in 1958 and completing his neurology residency at UCLA before moving to New York City in 1965.

It was during the late 1960s, when he was working as a consulting neurologist for Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, that Sacks encountered one of the first neurological “glitches” he would work with throughout his career. Sacks worked with around 80 patients who were catatonic survivors of the epidemic of “sleeping sickness”, or encephalitis lethargica, which had swept the world from 1916 to 1927. Sacks experimented by giving the patients levodopa (L-DOPA), which at the time was hailed as a miracle drug to cure Parkinson’s. The L-DOPA treatments miraculously awoke the catatonic patients, allowing them to emerge from their decades-long sleep. Some patients were able to stay awake and return to “normal” life while taking L-DOPA; others experienced uncontrollable side effects and were taken off the drug. Sacks chronicled his work with the “sleeping sickness” patients in his 1973 book Awakenings, which was eventually adapted into a feature film of the same name starring Robin Williams as Sacks.

Sacks worked with around 80 patients who were catatonic survivors of the epidemic of “sleeping sickness”, or encephalitis lethargica, which had swept the world from 1916 to 1927.

Sacks worked with patients experiencing a variety of neurological conditions throughout his lengthy career, some of whom he discussed in his books. Sacks’ 1985 bestseller The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat is composed of 24 essays, each delving into the case of a different patient. The title comes from an essay on one of Sacks’ patients who had visual agnosia, a condition that left the patient unable to recognize objects visually. For example, the patient could describe a rose as “a convoluted red form with a linear green attachment,” but it was only after he was asked to smell the object that the patient could identify it. Along with the struggles of people with neurological conditions, Sacks also wrote about the talents of some of his patients, such as twin brothers who were severely mentally impaired and could not read, yet were able to spontaneously come up with 20-digit prime numbers. Sacks’ essays presented his patients’ humanity, seeking to help the reader understand the world in which his patients lived.

Sacks’ essays presented his patients’ humanity, seeking to help the reader understand the world in which his patients lived.

Sacks’ work was extremely popular, with more than a million copies of his books in print in the United States. He was lauded for his work in academia as well, receiving honorary degrees as well as awards from numerous universities. However, Sacks’ writings did not come without criticism. Sacks was criticized by some scientists for “put[ting] too much emphasis on the tales and not enough on the clinical”, as put by Gregory Cowles of the New York Times. Additionally, some disability rights activists accused him of exploiting his patients for his literary career, to which Sacks responded “I would hope that a reading of what I write shows respect and appreciation, not any wish to expose or exhibit for the thrill, but it’s a delicate business.”

Sacks’ writings showed the reader a glimpse into the lives of some of his patients, ranging from those experiencing rare neurological “glitches” to those with more common disorders such as Tourette’s syndrome and autism. Through his illuminating writing style, Dr. Sacks was able to introduce the brain’s quirks to a general audience and demystify those afflicted with neurological disorders.

BMJ (2007). DOI: 10.1136/bmj.39227.715370.59