Cloning is evolving from sci-fi movies into laboratories. The idea of creating life — or even creating products of life — has always enticed humanity. Despite this fascination, the concept of cloning; whether of cells, animals, or humans; still fills most with unease and even disgust. Despite its unsettling connotations, billions of dollars have been invested into cloning research and potential applications. From curing illnesses to continued living with beloved pets, cloning has come a long way. The next destination on its path? Our stomachs.

Vegetarianism (and veganism) is on the rise. Arguments for why eating meat poses concerns — both physical and moral — are gaining traction. Current livestock farming takes up huge amounts of land and water when compared to crops, siphoning resources and reducing land available for crops to grow. It is also estimated to account for a third of all anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions to date.

Meat eating also raises concerns beyond the environment. Animals in livestock farms are often gravely mistreated. The cramped and stressful conditions are ripe for disease outbreaks — sometimes so intense that illnesses spread to humans. To maintain meat production levels and animal health, antibiotics are given to livestock. Microorganisms capable of becoming resistant to antibiotics are spread through this use. Whether through the meat itself or other methods, such as soil, water, and crops, antibiotic resistance can spread to any animal, including humans. With 70% of antibiotics that are medically important for humans used on livestock, antibiotic resistance is only increasing. In 2019 alone, at least 1.27 million deaths were attributed to antibiotic-resistant infections. With meat production showing little sign of slowing down, this number is likely only going to increase.

“Animals in livestock farms are often gravely mistreated. “

Despite these concerns, meat-eaters still make up a majority of the population. To understand this, The New York Times invited readers to make the strongest moral case they could for eating meat. The results said “surprisingly little.” A panel of judges chose the winning essay, but the public was also encouraged to vote on their favorite. The essay chosen by the panel claimed eating meat was fine because life and death are natural and inevitable. It also claimed that giving thanks and choosing ethically raised food are the necessary steps of morally eating meat. The essay that won the public over, however, was written by Ingrid Newkirk, a vegetarian about to go back to meat after 40 years because lab-grown meat is allowing for the consumption of real meat “without the mess and misery.”

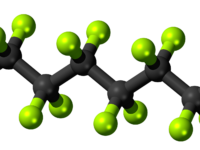

The lab-grown meat Newkirk is referring to is also known as in vitro meat, synthetic meat, clean meat, or cultured meat and is created by taking muscle cells from a live animal. These cells are injected with a nutrient-rich serum that causes the cells to double in number every few days. Once formed, the cells are encouraged to form muscle-like fibers, which are then artificially “exercised” like muscles to increase protein content and size. The tissue is then harvested and sold as regular boneless meat. In November 2022, the FDA approved a San Francisco startup to sell cultured meat. This was the first FDA approval for cultured meat, but the industry still needs to pass through USDA regulations before sales can start.

Newkirk’s view is based on the diminished harm cultured meat poses when compared to farmed meat. Without large amounts of livestock farming, animals are subject to significantly less (though not nonexistent) cruelty. There is less water use, less disease, less antibiotic use, and less deforestation. A 2011 life cycle analysis predicted the transition to cultured meat to reduce energy use by 45% and greenhouse gas emissions by 96% in the meat industry. A 2021 study revealed that recovering the 30% of Earth’s land surface currently used for livestock farming could be used to resolve 800 gigatons of carbon dioxide via photosynthesis.

Cultured meat is not without flaws. Due to it being early in the development process, concerns around the safety of consuming cultured meat are still prevalent. Some are concerned with the idea of corporations controlling our food. Others are concerned with decreased genetic diversity — a problem we’ve had before with crops like bananas. Even more are concerned with what is in cultured meat. Cultured meat is suspected to have unhealthy ingredients such as yeast and heme. Heme, when consumed in excess, is linked to colon and prostate cancer. Even the FDA has set limits on heme in cultured meat: The protein cannot exceed 0.8% by weight of cultured meat to be safe for human consumption.

Regardless, cultured meat has a lot of potential. It could optimize diets, reduce the suffering of farm animals, and even help the environment. Cultured meat allows meat eaters to no longer face the severe moral consequences that eating meat poses, whether due to religious reasons, health concerns, or environmental awareness. Those who are too attached to the taste will have a new, potentially culturally accepted, option for their meals.

For those who have already given up meat? Keep doing so. Mark Post, the first presenter of cultured meat, has famously gone on record to say “vegetarians should remain vegetarians.” Even with decreased harms, the best thing one can do for both the environment and the suffering of animals is to continue not consuming meat — bred or bioengineered. While suffering is reduced, some animals are still harmed in the creation of cultured meat. Similarly, while environmental concerns are less severe, the production still has flaws.

A future with cultured meat feels imminent and, when it finally becomes available to the public, already polarized responses are likely to skyrocket. A 2016 survey found that two-thirds of Americans were willing to try cultured meat, a third of which were definitely or probably willing to eat cultured meat as a replacement for farmed meat without even trying it. The willingness to try cultured meat suggests hope for the product. Assuming the taste and price of cultured meat compare to that of farmed meat when it is ready to hit the market, cultured meat has a higher chance of success than one might think.

The morality of meat-eating seems to exist on a scale. While one can view it as right or wrong, the logistics of the real world suggest that even the strongest moral case stands no chance against the most avid meat eaters. Cultured meat is providing a lesser wrong to those still seeking to eat meat. However, the existence of cultured meat is raising more questions about how we think about food and our willingness to consume it. Does where our food come from impact our morals when it comes to consumption? The answer to this question and similar ones is something we should all ask ourselves. How different is a lab from a factory? How do food corporations differ? Knowing the history and science behind the development of both farmed and cultured meat is an important piece of making the essential choice of what to put in our bodies.

- Animals (2013). DOI: 10.3390/ani3030647

- Journal of Animal Science (2020). DOI: 10.1093/jas/skaa172

- Nature Food (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s43016-022-00602-y

- Nature Food (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s43016-022-00601-z

- PLoS Climate (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000010

- Nature Sustainability (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-020-00603-4

- PLoS ONE (2017). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171904