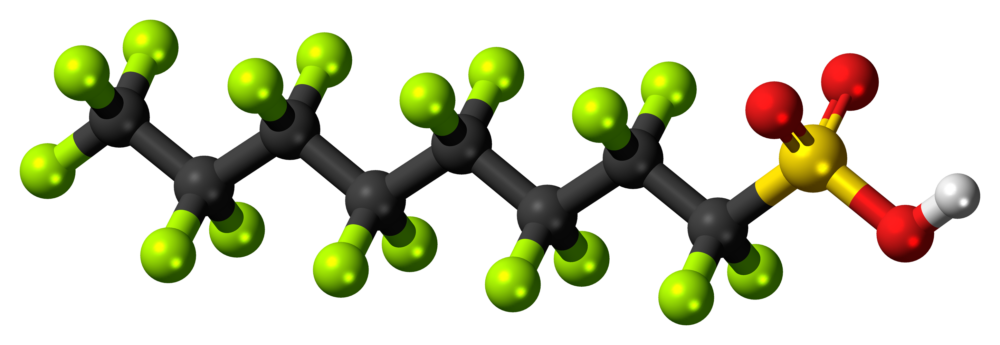

Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS, have persisted in the environment for decades, earning the name “forever chemicals.” These man-made chemicals, found in nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing, and grease-resistant packaging, have been manufactured since the 1940s, and have since impaired waters globally. PFAS contain carbon and fluorine bonds, one of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry, making them naturally indestructible. However, a newly developed PFAS treatment technology has questioned just how “forever” these chemicals may be.

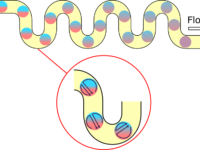

A team of scientists and engineers at EPOC Environmental in Australia designed a method of PFAS removal, known as “Surface Active Foam Fractionation” (SAFF), which solely utilizes air bubbles. In the process, gas (typically air) bubbles through a contaminated aqueous solution. Since PFAS are water-repelling surfactants, they tend to accumulate on the air-surface interface of these rising bubbles, creating a concentrated foam at the surface that offers a more targeted and effective removal. With the main input being air, this method of remediation could be sustainable, cost-effective, and feasible on a large scale. Foam fractionation has been an established technique since 1961, but its application for PFAS remediation was only recently discovered.

The Army Aviation Centre in Queensland, Australia, within the Great Artesian Basin, was the site of the first field study of SAFF. As one of the largest deep groundwater bodies in the world, former fire training and hot refueling activities from the Australian Department of Defense vastly contaminated it with PFAS. Along the field trial site, the team installed an SAFF plant within a shipping container containing a chain of treatment stages. The first stage, or primary foam fractionator, produces a PFAS-free solution, which is pumped through a polishing stage and released as clean water. The contaminated foamate from this primary tank is separated from the solution, and a second fractionation vessel receives this surface foam, concentrating the substance further. Within a tertiary fractionation tank, the foamate left is enriched in PFAS, leaving only a small volume of highly concentrated substance for periodic disposal, potentially through incineration. The team sampled water upstream of these SAFF tanks and downstream of the SAFF plant to measure PFAS presence. In all 35 samples, SAFF removed around 99.5% of three primary PFAS types.

“In each of the 35 samples at all sites, SAFF removed around 99.5% of three primary types of PFAS.”

Unfortunately, the SAFF technique is not as effective on shorter-chain PFAS molecules with lower absorption coefficients, leaving behind some contaminants in treated waters. A follow-up treatment, known as anionic exchange (AIX) resin polishing, can remove 100% of all detectable PFAS chemicals from sampled water when used downstream of SAFF methods. AIX resin works to replace ions in the contaminated solution with ions of a similar electrical charge. When used in combination with secondary downstream treatment techniques, SAFF is extremely effective in reducing PFAS concentrations to drinking water quality standards. These additional treatment technologies, however, do not offer the sustainability of simply utilizing air bubbles; Resin must be replaced and disposed of, whereas SAFF alone generates zero waste.

Allonnia, a bio-ingenuity company based in Boston, Massachusetts, has begun to distribute this PFAS treatment across North America, offering SAFF units to provide a sustainable solution to PFAS contamination. PFAS are prevalent in nearly all major water supplies in the United States and are also present in the atmosphere and soils. In groundwater, PFAS spreads across long distances and can contaminate drinking wells. Manufacturers were not required by the EPA to report the use of PFAS in products until a final ruling in October 2023, making these chemicals inconspicuous for years. The 2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey detected PFAS in the blood of 98% of Americans. Even at low exposure levels, PFAS can lead to cancer, liver or kidney disease, altered thyroid function, and a myriad of other health effects. While the use of PFAS has become restricted recently, these chemicals are still present and extremely persistent in contaminated water resources, making SAFF a crucial treatment in protecting humans and ecosystems from exposure.