Crisp apples, plump tomatoes, juicy berries, and citrusy oranges are endless luxuries in the middle of Boston’s cold, dead winter. Despite slush and ice covering grass and sidewalks, grocery shelves are fertile with everyone’s favorite produce. However, the fresh fruits and vegetables that fill the aisles involve a lengthy journey and intense science to get avocados and limes to frigid New England. Moreover, 33 percent of that produce is thrown away after harvest in the trek from farms to shelves to our homes.

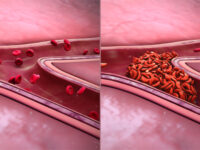

The intentionally discarded produce is called postharvest waste, a growing, worldwide concern. This occurs as a result of the consumer’s desire for the best product. This means casting aside bruised peaches, bad apples, and cracked tomatoes, although they are perfectly edible. In a review published by Nature’s Horticulture Research, researchers at the University of California, Davis analyzed the causes, impacts, and solutions to postharvest waste. Why does perfectly edible produce get thrown away by grocery stores, and how can it be preserved?

It starts with the general public lowering their standards. “Perfection is not something that should be applied to fruits and vegetables,” said Dr. Diane Beckles, a postharvest biochemist and study author. “There is an element of capitalism that influences the produce market, where we have unrealistic expectations based on what we see on TV or in paintings or cartoons of what fruit and vegetables are supposed to look like… There are going to be imperfections, blemishes, and variability in the quality.”

Moreover, 22 percent of that produce is thrown away after harvest in the trek from farms to shelves to our homes.

But can consumers have these high expectations for their produce when it travels thousands of miles across a highly extensive supply chain to meet their shelves? As Beckles and her colleagues highlight, these supply chains can last months. Although fresh, perfect produce cannot withstand that timeline, there are many methods by which the produce is preserved to attempt to meet the expectations of the consumer.

Ethylene is one hormone produced after harvest that creates the tastes, textures, and flavors that we love in ripe fruit, but it also causes the produce to age and senesce. This results in unfavorable bruises and blemishes on the invaluable fruits and vegetables as they travel along the supply chain.

“Ethylene is a friend and a foe,” Dr. Beckles underscores. “If you want to be able to control the shelf life of some produce, then you have to be able to manage ethylene.”

Ethylene production is targeted by many elements in the supply chain that are used to regulate the environment of the produce. It can be managed through metabolic inhibitors, temperature control, and coatings throughout the produce’s postharvest timeline. But the study authors propose a different mode of action, using gene editing tools to regulate the production of these ripening chemicals. One common tool for controlling plant genes is CRISPR-Cas9, a microbe-based gene editing technology.

“There is an element of capitalism that influences the produce market, where we have unrealistic expectations based on what we see on TV or in paintings or cartoons of what fruit and vegetables are supposed to look like… There are going to be imperfections, blemishes, and variability in the quality.”

Although CRISPR seems like the answer to just about everything nowadays, there are still many challenges that this methodology faces. The authors of the review highlight the war over CRISPR patenting. The Broad Institute, located on the Cambridge side of the Charles River, currently owns the United States patent for CRISPR editing in eukaryotic cells, which applies to all produce. The University of California holds the same patent — but for Europe, China, Australia, and Singapore. Although these groups allow CRISPR research in academia, it constricts the work of private sector companies in increasing the lifespan of everyday produce.

Gene editing technology is also highly regulated throughout Europe, preventing many gene-edited crops from entering the market and therefore from reducing postharvest waste. Another roadblock in the path to long-lasting spinach is growing societal concern over genetically-modified organisms.

“People often think of it as an invasion of nature, but it’s more like coaxing plant growth to be suitable for modern agriculture,” detailed Dr. Beckles. “We humans have been doing this for the past ten thousand years.”

In a world where food insecurity only grows with global climate change and overpopulation, it will be necessary to conserve and value the produce that is grown each year, using some of science’s most innovative technologies. For Beckles and her group, this review was a necessary step to opening the conversation of postharvest waste.

“We wanted to educate the public about the severity of the problem,” said Dr. Beckles. Proposing answers like CRISPR to improve the amount of postharvest waste illustrates that “there are practical solutions out there that can go a long way toward solving these complex problems.”

Sources: 1

Image Source: Pixabay