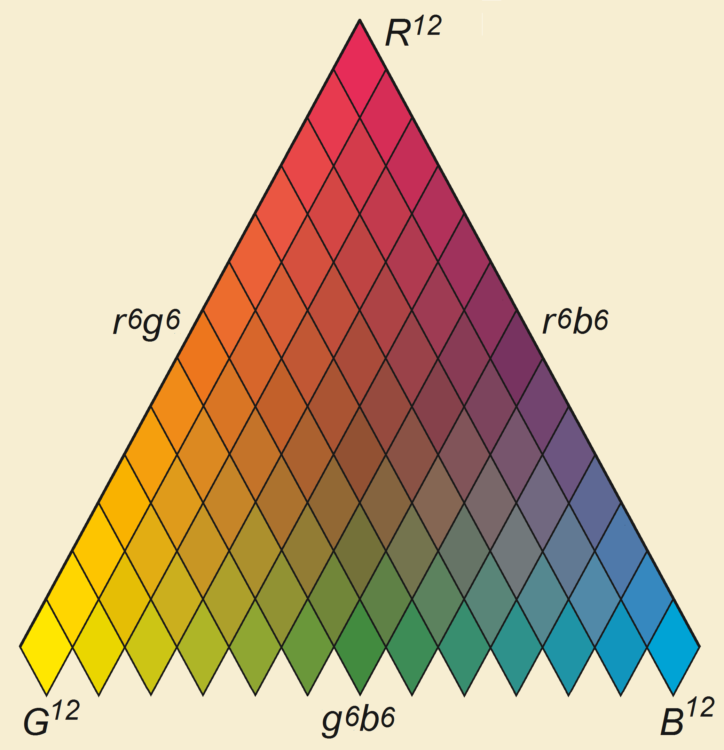

Everyone knows the color wheel; red, yellow, and blue combine to make orange, green, and purple, all of which combine to make the spectrum. While this system works well for understanding pigments, it breaks down when considering mixtures of light, where red and green make yellow and white is a tertiary color.

To explain these inconsistencies, we turn to color theory, which aims to understand the mixing of colors across all media as well as the mechanism by which we see color.

In 1801, Thomas Young, an English polymath famous for his work on light propagation, became among the first academics to propose a trichromatic theory of light. While earlier minds like Isaac Newton believed the human eye saw every color individually, Young posited the eye saw three color primaries: red, yellow, and blue.

As it turns out, the human retina detects light via two types of photoreceptors: cones and rods. Rods measure light intensity and are responsible for monochromatic vision, while cones measure color intensity. Cones come in three varieties, L (long-wavelength), M (medium-wavelength), and S (short-wavelength), which detect red, green, and blue intensity, respectively. Our perception of chromatic hue is the brain’s interpretation of the mixture of these three signals.

However, this process can go awry. Since the brain relies on mixed signals to deduce a color’s place on the spectrum, when an impossible combination occurs, the brain “short-circuits.” Most famously, when the brain experiences red and blue signals but no green, the result is magenta, even though the color lacks an associated wavelength. Inversely, the sudden removal of a continuous stimulus will produce an afterimage dubbed a chimerical color. For example, when a yellow signal is suddenly switched to black, the resulting afterimage will be an impossibly dark color called stygian blue.

This overview only scratches the surface of one particular theory of vision, known as Young–Helmholtz Theory. Though one of the most popular theories of color perception, it fails to explain chimerical colors, as the color wheel fails to explain light.

Nevertheless, we see magenta, even when it theoretically should not exist. Though an elementary concept, color is not fully understood, with current research exploring its perception as additive, subtractive, and even psychosomatic. As this corpus of knowledge grows, so shall our theories of color, parsing the brain’s beautiful lie.

Sources:

The Constructive Nature of Color Vision and Its Neural Basis (2017). DOI: 10.15496/PUBLIKATION-19815

Neurociencias (2008). PMID: PMC3095437

Philosophical Psychology (2005). DOI: 10.1080/09515080500264115

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons