Off the coast of mainland Australia, the small, sun-baked island of Tasmania houses nature’s most feral creature. With a piercing shriek, lingering stench, and penetrating eyes, the Tasmanian devil reigns as the largest carnivorous marsupial in wildlife. Its ever-growing teeth sink into bones and feast on the bloody, meaty flesh of its latest catch. As self-proclaimed “lone wolves,” Tasmanian devils hunt solo and are known to brawl with their own over prey. And yet, while being physically prepared for any possible attack, they are helpless under the restraint of an invisible predator that has eradicated more than 60% of their entire population. This silent assailant is a contagious cancer known as Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumor Disease (TDFTD). This disease defies what we thought we knew about cancer, and therefore is a topic of high interest for many genetic and conservation biologists.

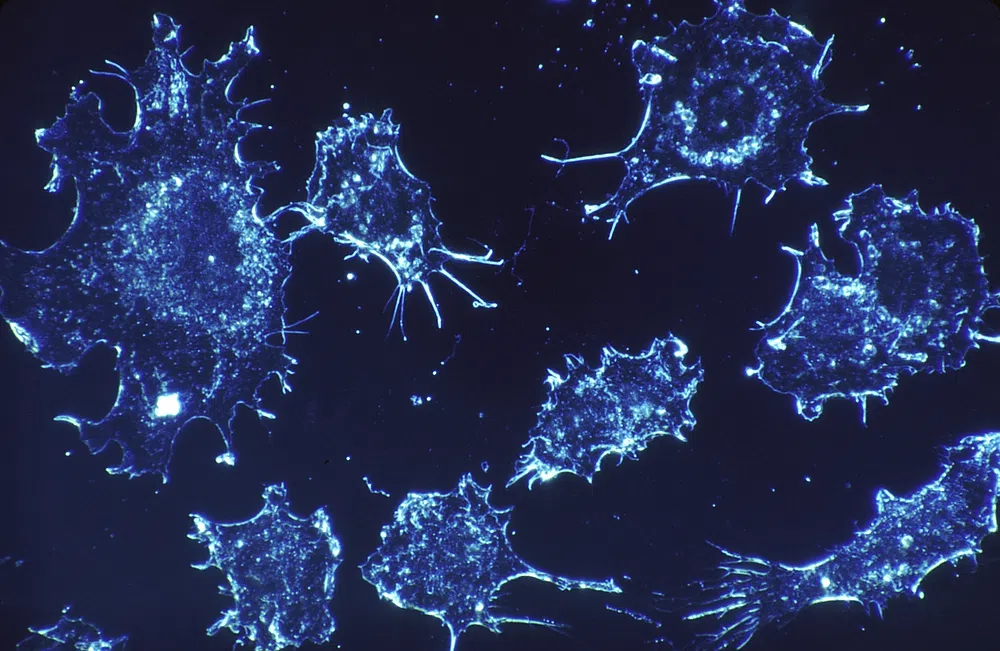

Through centuries of research, scientists have noticed foundational patterns in the unpredictable nature of cancer. Cancer is the uncontrolled growth of cells leading to the formation of tumors. These tumors can grow and migrate throughout the body, characterizing metastasis and disrupting healthy, vital tissue. The cause of this abnormal growth traces back to genes and their mutations. In the perfect storm of cancer, the genes associated with cell division and cell death are altered so cell division is overexpressed or cell death doesn’t occur when it needs to. These alterations happen spontaneously through environmental factors or inheritance. This is why smoking, sun exposure, or having a relative with cancer are known to increase the chances of getting the disease. Therefore, it is impossible to directly “catch” a cancerous mutation like one would catch a cold.

And yet, while being physically prepared for any possible attack, they are helpless under the restraint of an invisible predator that eradicated more than 60% of its entire population.

Scientists have considered this principle strictly with the nature of cancer and its causes until the curious mass disappearance of Tasmanian devils. Researchers noticed that the dead Tasmanian devils had lumps on their faces, which were later found to be malignant tumors that were killing the animals. However, what didn’t make sense, based on what was known about the basics of cancer, was why such a significant portion of the population was being affected and killed. Elizabeth P. Murchison and her team of researchers at the University of Cambridge spearheaded this inquiry, which led to the discovery of TDFTD. By sequencing the microRNA of the tumors, they discovered that the cancer was spreadable by contact. When Tasmanian devils fight and bite each other, the cancerous cells physically move from one devil to another. These cancerous cells then evade the animal’s immune system and eventually multiply to form a tumor. This refutes what scientists thought they knew about the causes of cancer and the genetics of the disease.

Due to the large impact that this disease had on Tasmanian devils, conservation biologists have been working to try to increase the population. Isolation of the disease, vaccines, and natural immunity development have helped further this goal and ensure survival for Tasmanian devils. More recently, researchers have been able to use phylodynamics, a way to map the ancestral genetic history of pathogens, to assure that the Tasmanian devil species triumph over the disease. So, while these devils are not the most friendly of creatures, studying them has allowed us to push the boundaries and realize the deviance of cancer.

Image courtesy of Rawpixel