For decades, Mars has been the planet in vogue: the possibility of exploration, even colonization, beyond the Earth system captured the imagination of the public (as well as certain billionaires). But such a mission might be more technically challenging than we’re ready for. Transit of up to a year each way makes it difficult to abort the mission if something goes wrong, and inhospitable surface conditions upon arrival (hazardous radiation, freezing ambient temperatures, and surface pressures far less than those on Earth) demand significant protective measures. One NASA mission concept, dubbed HAVOC (High Altitude Venus Operational Concept), contends that a mission to Venus – first robotic, then with a human crew – is the practice run needed to make a larger-scale Mars mission go smoothly in the future.

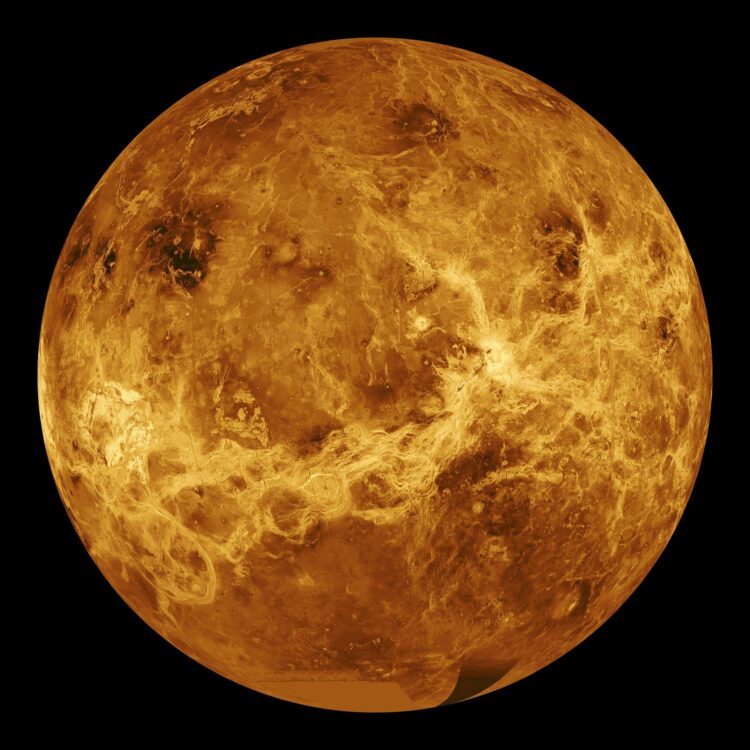

The plan to explore Venus first may come as a surprise, since the Venusian surface is a nightmarish hellscape. At 735 K (863 °F) it’s hot enough to melt lead, with crushing pressure 92 times that at Earth’s surface; its atmosphere, consisting mainly of carbon dioxide and highly corrosive sulfuric acid, is so thick it blocks nearly all sunlight from reaching the surface. These conditions are so harsh that surface probes landed by the Russian Venera mission only lasted between 23 minutes and two hours before disintegrating.

But above the thick cloud cover, conditions are much more clement. At an altitude of 50 to 65 kilometers, temperatures and pressures resemble those on Earth. The proposed airships would ride winds over 220 mph at this balmy altitude, coasting on an atmosphere rotating faster than the planet itself. Cruising at that altitude provides an environment stable enough to conduct science, as well as possibly establish permanent settlement.

It’s theorized that Venus was an Earth-like haven during its first two billion years, with clement temperatures, a shallow liquid water ocean, and a less cloying atmosphere.

Mars-related motivations aside, Venus is intriguing as our closest cousin in the solar system. It’s theorized that Venus was an Earth-like haven during its first two billion years, with clement temperatures, a shallow liquid water ocean, and a less cloying atmosphere – conditions considered markers of habitability. But then the planet started to heat up, oceans boiling away as the runaway greenhouse effect cooked its surface into a hostile wasteland. Though its heyday of habitability is long gone, Venus is bound to carry fingerprints of its past history, perhaps harboring evidence of ancient life.

Venus presents a unique opportunity not only to learn about Earth’s closest analogue, but also to dry-run the technology we’ll need to make a Mars mission possible. A trip to Venus will take half the time of a Mars mission, and allows crew to abort back to Earth if things go wrong. It also provides a practice run for creating durable habitats: making radiation-resistant, non-corrosive, inflatable airships poses a daunting engineering challenge that will prepare scientists for even greater hurdles on Mars.

Whether you’re compelled more by the scientific or engineering objectives, this mission will ultimately be another exercise in human imagination and resourcefulness. Decades of science fiction could be realized when humanity’s first space colony becomes a city in the clouds of a foreign planet.

Image source: Pixabay