In many ways, science is a discussion. Many within the community know all too well about the rivalries and bickerings between academics and scientists, the workplace politics that plague every human endeavor. However, the way that we’re usually taught science emphasizes facts: 1 + 1 = 2, the Earth is a sphere, and gravity will bring you back down to Earth if you jump up. Science is observation: a summary report of what we learned and what we know now. Yet science is very much a subject, living and acting, shaping the discussion as much as it is the object of the discussion. Science as a process is nothing new, but it’s an idea that’s often forgotten. We laugh at the people back in the Bronze Age who thought the Earth was flat, but it was just as necessary to have that idea as it was to pose a contrary hypothesis that the Earth was spherical. Our tentative knowledge of Earth’s shape was imperfect, but it created a space to justify that position. Empiricism and the scientific method paved the way for finding evidence to support the hypothesis of a round Earth, and now that fact is solidified in our repertoire.

Science is very much a subject, living and acting, shaping the discussion as much as it is the object of the discussion.

Some cases are less clear, and the discourse is more hotly contested. For example, the concept of species taxonomy isn’t as absolute as the shape of the Earth. There are at least a dozen species concepts that might classify a single organism as many different, distinct species. While it might be easy to tell a human apart from a dog, it’s more difficult to tell different mosquito species apart. Based on morphological characteristics, six species of Anopheles were misclassified as a single species, but genealogical data shed light on that mistake and corrected it.

The imperfection of taxonomy highlights the tentative nature of scientific knowledge, and as our methods for discovering evidence improves, so too does our understanding of the world. Scientists create arguments and support them with the best available evidence. However, new arguments and explanations can come along as we build upon others’s work, and as a result, those new arguments can defeat older ones. This does not mean that science is completely futile and untrustworthy; it means that knowledge should be analyzed. Critically analyzing scientific conclusions is an important skill. Doubt and skepticism should not aim to reject and abandon but iterate upon what is already known — that is, evidence should be presented in a more convincing way to support a better conclusion.

Doubt and skepticism should not aim to reject and abandon but iterate upon what is already known

A few questions present themselves for the layperson: If science is so tentative and uncertain, why should they trust scientists and the scientific community? Why does the scientific method provide the best evidence for knowledge about the world?

Trusting science means trusting that empirical evidence is the best way to develop knowledge about the world, and one of the best ways to learn about one’s surroundings is through the senses. At the most fundamental level of comprehension, we have to trust our somatic senses and our observations. Science offers us the ability to systematically collect data and confirm or reject our predictions based on that fundamental way of knowing. Conclusions about those predictions are based on repeated observations; if you see something enough times, likely, that’s always the case, but there’s always room to be proven wrong.

Trusting science means trusting that empirical evidence is the best way to develop knowledge about the world, and one of the best ways to learn about one’s surroundings is through the senses.

The standards for producing statistically significant results are rigorous, and they help the credibility of science, but accountability to the community also contributes to that. Peer review is an essential part of research and publishing in academic journals because it maintains the scientists’s and the journal’s credibility. Independent scientists rely on the quality data of others to develop their own findings and papers, so they have a vested interest in supporting the best available research. While the peer-review process does not catch every paper and journals may issue retractions, a journal’s openness to admit their mistakes is a reason to trust that the knowledge they’re disseminating is sound.

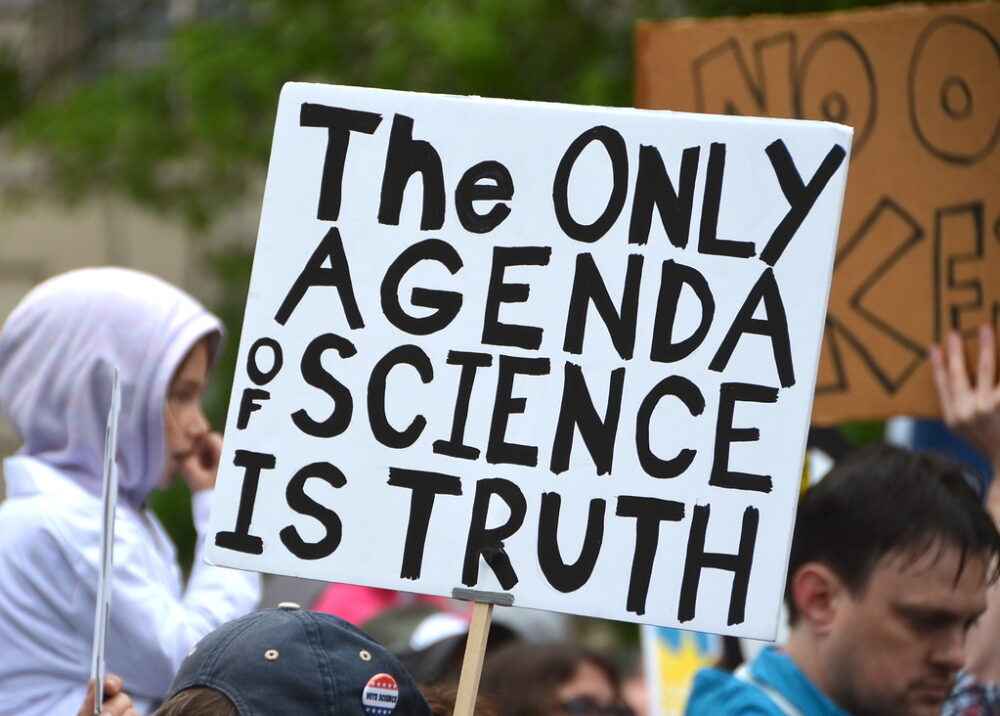

Science looks for an answer, and the contention inherent in the field is exactly why it should be trusted and questioned, not questioned and dismissed. Scientists’ shared pursuit of knowledge and the process’s integrated skepticism and criticalness are crucial to the field maintaining its accountability and credibility. Although some spread misinformation in bad faith, there will always be a greater community of truth-seekers.

Systematic Biology (2017). DOI: 10.1080/10635150701701083