The STEM of Their Interest: The Lit Review Does Come Through and Emily Navarrete in the Williams Lab

By Hugh Shirley, Biochemistry 2019

This is the final of four pieces in the “STEM of Their Interest” series by Hugh Shirley, featuring Northeastern undergraduates and research labs. This piece was originally published as part of our Summer 2018 series.

A lab at Northeastern University comes in many shapes and sizes, and the undergraduates that work in those labs are just as diverse. How students got there, what drives them to put in the hours every week, and what they are passionate about is the subject of this series. We spoke with students in labs around campus to learn about what they do and why they do it.

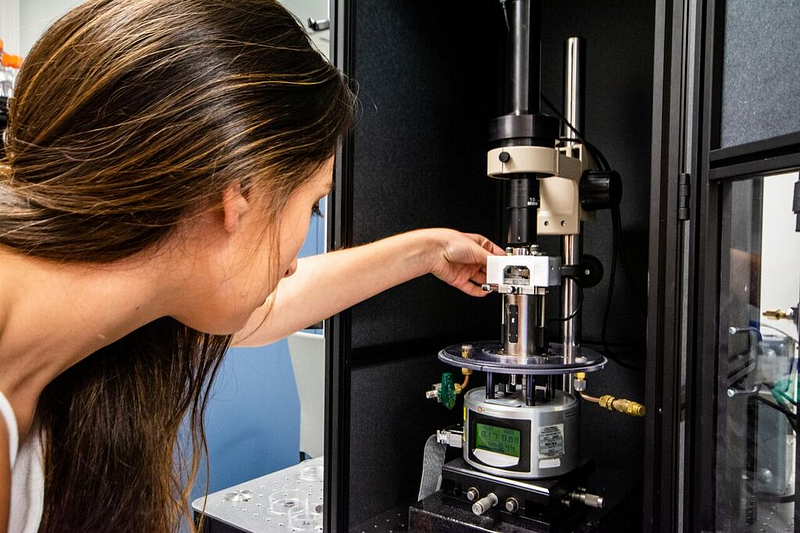

Deep in the bunker-like halls of Dana Research Center at Northeastern University, Emily Navarrete, a fourth year Cell and Molecular Biology major tinkers away in the Williams Lab. The Williams Lab conducts biomolecular physics research. They look at tiny single molecules and how their atoms interact with each other and build to form more complex structures. One of several projects the lab works on involves histones, the proteins that help coil chromosomes into a more condensed form. For over a year, Navarrete has worked in the lab’s Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) room on one of the most difficult challenges of her undergraduate career.

For over a year, Navarrete has worked in the lab’s Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) room on one of the most difficult challenges of her undergraduate career.

Navarrete first came to the Williams Lab during her search for a co-op. The Williams Lab offered an interview too late for her to accept, but Navarrete did ask if she could still have a tour of the lab. During that tour, she was offered a summer research position. A postdoc in the lab had just finished setting up the AFM before leaving without anyone to replace her. The PI “figured that since they already gotten someone to figure out all the kinks that would be easy for an undergraduate to take on,” Navarrete said. It turned out to be a little bit more difficult than anyone anticipated.

The project Navarrete began working on involved imaging DNA using the AFM. A small disc with DNA adhered to the surface was supposed to be visualizable on the AFM, but the project quickly ran into some trouble. Normally, the AFM works by running a tiny needle over the surface of the disc and causes the metal strip to which its attached to bend slightly when the needle moves up and down over the tiniest of molecules, like DNA. A laser that hits the metal strip detects the change in height as the strip bends and creates an image that can be used to examine the molecules on the surface of the AFM. This was not happening, something was preventing the AFM from picking up the molecules on the disc’s surface.

“It was a lot of tinkering around with the various instruments, a lot of literature reading because I hadn’t learned about AFM before.”

During her first few months in the lab, Navarrete was just trying to wrap her head around the AFM, how it worked and how to use it. “It was a lot of tinkering around with the various instruments, a lot of literature reading because I hadn’t learned about AFM before,” Navarrete said. Reading the literature is a recurrent theme in Navarrete’s lab experience, and it turned out to be one of the keys to solving her AFM woes when it turned out that something wasn’t quite right.

The discs Navarrete uses in AFM imaging were not flat enough. For the AFM to measure the tiniest bumps on the disc, the disc itself has to be totally flat. It was not. It took a long time before anyone in the lab was able to figure out what was wrong with the AFM.

But who finally did figure it out? Navarrete.

How did she do it? By reading the literature.

“I started out with what I do whenever I realize that there’s a problem, or there’s something I don’t fully understand, by doing a literature search,” Navarrete said. Then once she understood what the problem was, Navarrete went right back to more reading. Navarrete tackles problems by “knowing what I’m doing to fix it instead of just trying out different things and hoping that it’s going to work,” and she suggests this method for other undergraduates, too.

Navarrete’s experience in biology and chemistry research then came in handy. The solution to her AFM problem was to develop a special coating for the disc. Navarrete turned to her chemistry lab for help to “come to a solution with people that understood the chemistry,” Navarrete said. Now that she’s found and fixed the problem, Navarrete was able to produce images of DNA for her lab to use.

“I know that every experience that I get is an opportunity to learn more about something that I haven’t learned about before.”

Her experiences have helped shape the direction that Navarrete wants to take for her career. But since it’s its still early on “everything that I learn about excites me, so I haven’t refined what area of science I’m most excited about and want to go into,” Navarrete said. “But I know that every experience that I get is an opportunity to learn more about something that I haven’t learned about before.” Starting that learning experience earlier is something Navarrete wishes she had done, and something she suggests for other undergrads just starting out. She realized that she “was too afraid to take an opportunity when I saw it the first time around,” Navarrete said.

It took Navarrete over a year to realize that PIs on campus want to mentor students. They want students to ask questions and to learn. “Most PIs that are excited to take in undergraduates are excited to do so because they like to mentor students and see them progress,” Navarrete said. Going out and talking to PIs can be intimidating, but you can get so much out of it. That’s what Navarrete suggests, that and reading the literature. You never know what you can learn by perusing what’s already out there. Maybe you’ll even find the answer to the question that’s been plaguing your lab for months.