The STEM of Their Interest: iLOV E. coli featuring Trina Hong and the Lewis Lab

By Hugh Shirley, Biochemistry 2019

This is the second of four pieces in the “STEM of Their Interest” series by Hugh Shirley, featuring Northeastern undergraduates and research labs. This piece was originally published as part of our Summer 2018 series.

The Lewis Lab, one of the largest research labs on campus, has been the site of exciting discoveries in recent years. Research into uncultured bacteria, those bacterial species that cannot be cultured under standard laboratory conditions, resulted in a publication in Nature detailing the development of groundbreaking new methods of culturing bacteria in their native environments and the discovery of a new antibiotic. The lab’s continuing research into uncultured bacteria, as well as the study of Lyme Disease, persister cells, the microbiome, and more has continued to draw undergraduates hungry for research experience. Enter Trina Hong.

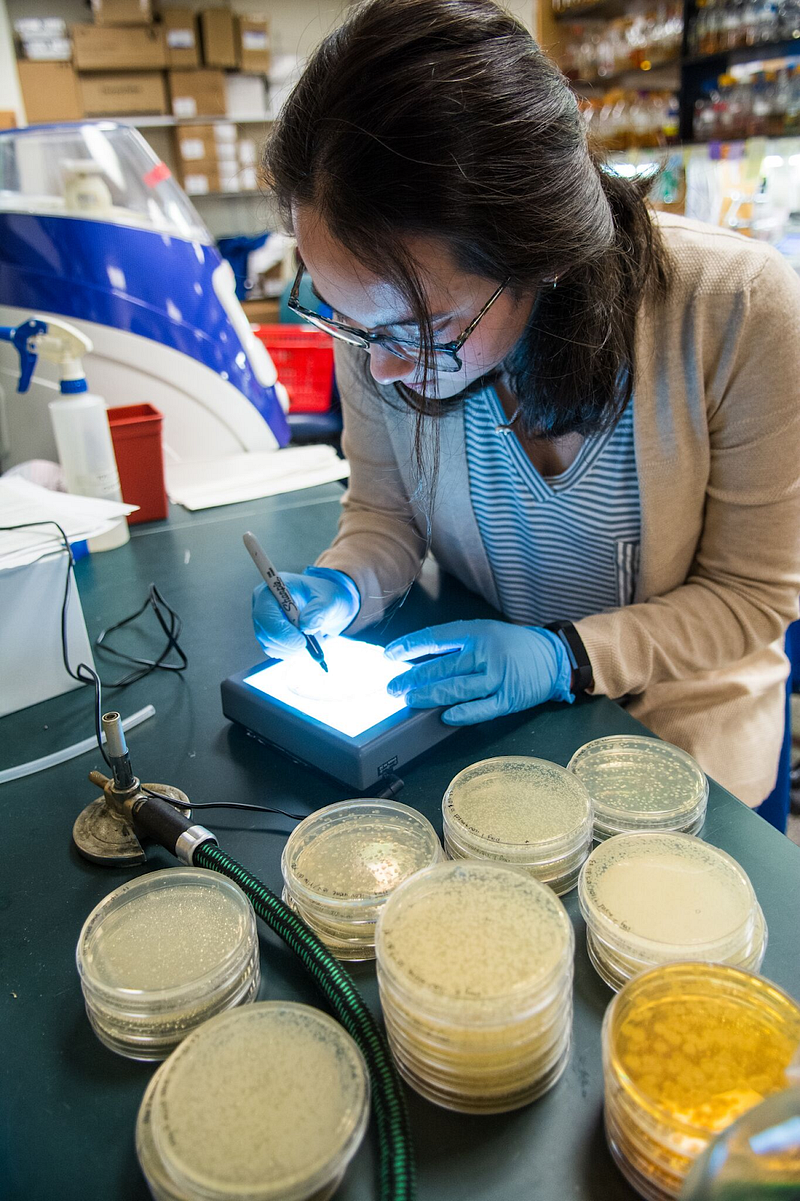

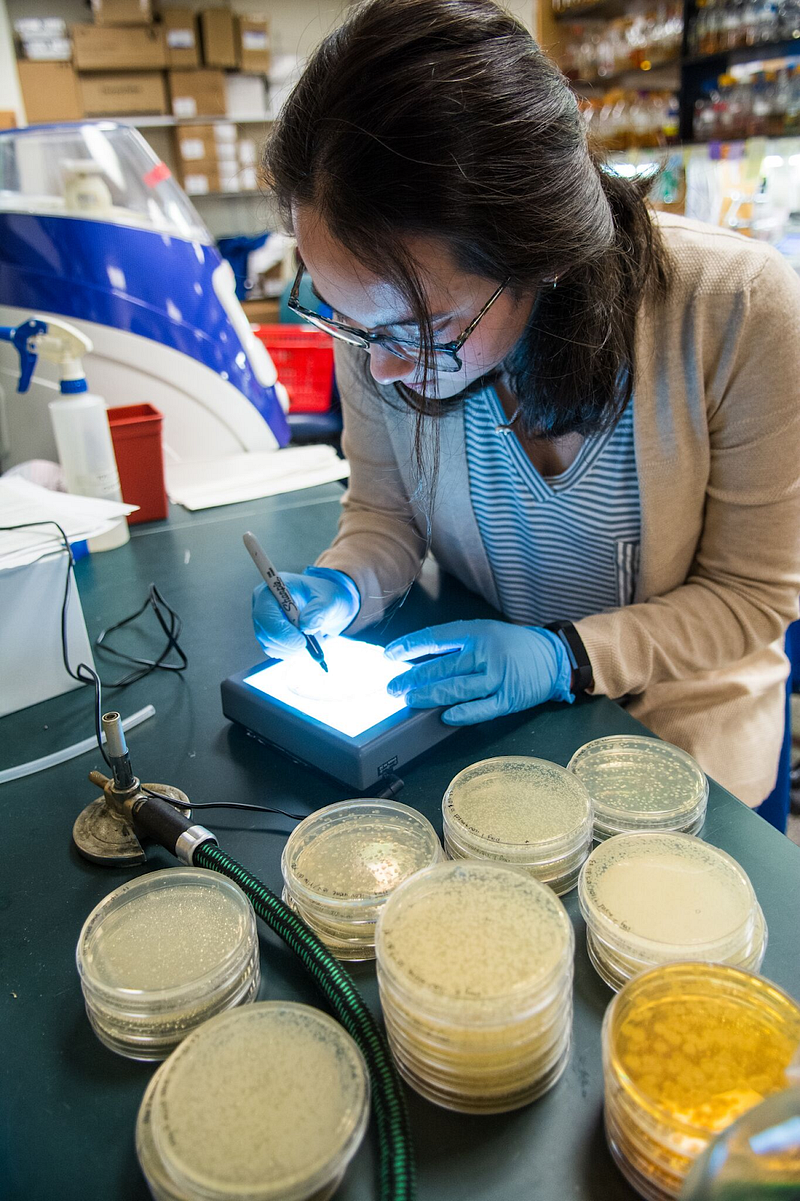

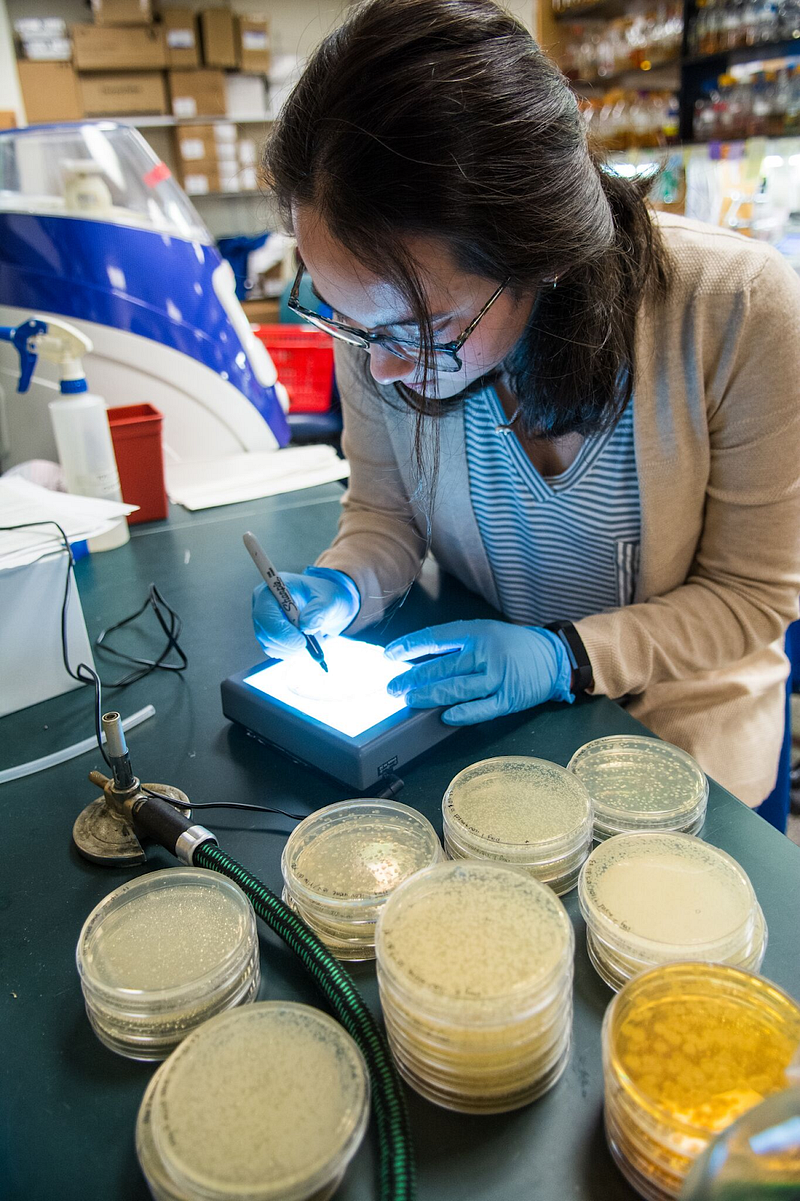

Hong and the Lewis Lab are the subjects of the second in a series of NU Sci articles on undergraduates in labs around Northeastern’s campus in many different fields. Since her freshman year, Hong has worked in the Lewis Lab and rose from dishwasher, plate pourer, and media melter all the way up to experiment designer as a key member of the team. I met Hong for a tour of the lab and spoke with her about her experience working there.

Since her freshman year, Hong has worked in the Lewis Lab and rose from dishwasher, plate pourer, and media melter all the way up to experiment designer as a key member of the team.

The Lewis Lab has many projects running concurrently, but Hong has focused her attention on one of the biggest topics in biology research today, the microbiome. The gut microbiome is the community of bacteria that live symbiotically within the small and large intestines. Hundreds of different bacterial species call the human gut home. Over time, the gut’s bacterial population can change due to alterations in the environment; shifts in diet, stress, and overall health can impact the composition of the microbiome for better or worse. Hong looks at changes for the worse.

Enterobacteriaceae is a family of bacteria that includes Escherichia coli, Yersinia pestis, shigella, salmonella, and many other pathogenic and nonpathogenic species. Hong works with other researchers in the Lewis Lab on E. coli. As the microbiome changes, it can “enter a state of dysbiosis,” and E. coli, along with other pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae “may bloom and result in harmful inflammation.” Bacterial bloom describes rapid population growth, and Hong’s work revolves around preventing E. coli bloom in the microbiome.

To do that, Hong had to be able to pick E. coli out of a sample containing many microbiome species mixed together. Enter iLOV, a gene sequence that causes fluorescence in anaerobic conditions, the environment of the gut. Hong transformed E. coli to express iLOV, which allowed her to pick out and measure E. coli growth from a mixed culture. During the course of these experiments, Hong’s work took a more independent turn. “We started running all these assays and they just weren’t panning out very well,” Hong said. Her principal investigator (PI) took a step back from Hong’s project during that time to focus on other areas of the lab and left it up to Hong to figure out what was going wrong.

Hong discovered that their assays were running into problems because of the microbiome sample their cultures were made from. Once a new sample had been obtained, Hong’s assays began showing what she expected. During that time, Hong’s PI was out of the lab, and the task of establishing and testing the new microbiome sample fell completely on Hong’s shoulders. That meant coming into the lab every day to make sure things were running smoothly. While that level of commitment wasn’t what Hong has originally anticipated, her involvement in the project has dramatically changed her career goals and outlook on research.

“I learn so much more in the lab than I do in classes. You pick up on the things that are very relevant to your work, and because they are relevant you pay attention to them and you internalize them a lot more.”

Hong, a Connecticut native, knew she wanted to go to medical school and that research was a box to be checked off on that journey. After our tour of the Lewis Lab, we met for dinner at a nearby cafe to talk about how she got to her position and how her work has changed her. “I wanted to do an MD, I didn’t think I wanted to do research, I saw it as an avenue to get to med school.” Hong said between bites of a sandwich. Since then, working in the Lewis Lab has changed her outlook, and she has set her sights on continuing research. “I learn so much more in the lab than I do in classes,” Hong said. “You pick up on the things that are very relevant to your work, and because they are relevant you pay attention to them and you internalize them a lot more.”

Taking a step into independent research from a guided experience can be a big, scary leap for a lot of people, and that transition took a lot of work on Hong’s part. “I was extremely nervous freshman year,” said Hong about the beginning of her time at the Lewis Lab. “They would be like ‘streak out a plate’ and I would freak out and think ‘I can’t do it, I can’t do it!’” It took her some time away from the Lewis Lab, at a summer internship at Mass General Hospital, for Hong to pick up the skills that helped her the most, independence and confidence in the lab.

While it took some time and experience in different labs, Hong has become more used to working in a lab and has enjoyed the experience enough to reconsider her overall goals. For those just starting out on their path, Hong has some advice.

First, find out what’s happening on campus. Look around, search online, talk to people. Find a lab that’s doing something that you’re interested in. Second, be selective. Don’t mass email. Once you find the lab you’re interested in, learn as much as you can about what they’re doing so that you can talk about it with the people that work there. Third, once you are in a lab that you like, don’t hop around. Stay in on the team for awhile, get to know everyone and what they’re doing. The longer you’re with them, the more opportunities you’ll get to be independent. And lastly, “If it’s not something you like, then maybe it’s not for you. Don’t torture yourself,” Hong said, shrugging as we finished eating.

Hong’s ongoing journey through the Lewis Lab is informative. The dedication and passion it takes to keep going back over a year and half despite the homework, despite the weather, despite whatever else might be bogging her down shows when Hong speaks about her project. Even if you don’t start with that passion, if you just need a check in off pre-med box, Hong’s story shows how and experience can shape and change you, and help you discover something about yourself that you didn’t know of before.