It is widely believed that one is completely disconnected from the outside world during sleep, unreactive to anything happening around them. New research, however, reveals that this may be far from the truth; in a recent study, researchers led by Delphine Oudiette, Isabelle Arnulf, and Lionel Naccache at the Paris Brain Institute found that during certain periods of sleep, people are able to process and accurately respond to external information at a high level of cognition.

Prior research has shown that there is active unconscious sensory processing during sleep, such as the learning of new information or processing of external stimuli, at least occasionally. Most research studying consciousness during sleep, however, does not account for variation among populations, which makes it difficult to generalize and confidently draw conclusions about findings when studying such a complex topic. Because of this, Oudiette, Arnulf, and Naccache’s team sought to obtain more subjective data by analyzing behavioral responses, which are often assumed to be impossible during sleep and therefore neglected in previous research.

In the past, the team showed that people could respond to questions sent while experiencing REM sleep, in which they are conscious of being asleep and dreaming. In this recent study, they wanted to study consciousness in almost all sleep stages and examine neural activity in addition to behavioral responses to stimuli during the trials. Researchers studied brain activity and eye and facial movements of 49 napping participants to determine whether communication is possible during REM sleep, in which sleepers are most responsive, and most other sleep stages. 27 of these participants had narcolepsy, a sleep disorder that causes excessive daytime sleepiness and uncontrollable sudden sleep attacks. Narcoleptic individuals tend to quickly and easily enter the lucid REM sleep stage, in which they are aware of being asleep. The higher likelihood of lucid dreaming made them the ideal candidate, as researchers predicted that participants would be most responsive during this stage due to their past work.

“Participants performed a lexical decision task while napping – they either smiled or frowned depending on whether a verbal stimulus, presented in one-minute periods alternating between off and on, spoke real or fake words, respectively.”

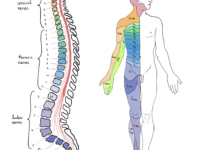

Participants performed a lexical decision task while napping – they either smiled or frowned depending on whether a verbal stimulus, presented in one-minute periods alternating between off and on, spoke real or fake words, respectively. Electromyogram (EMG) sensors, which detect muscles’ electrical activity, recorded contractions associated with frowning and smiling to generate behavioral data. Researchers also analyzed electrophysiological markers, such as specific brain signaling patterns, associated with higher and lower cognitive states, or states of increased and decreased brain activity, respectively, in order to determine whether a richer cognitive state during stimulation corresponded with higher response rates.

“Participants in both categories displayed a response accuracy of at least 70% across all sleep stages, although accuracy and response rates decreased with the depth of the sleep stage.”

Participants in both categories displayed a response accuracy of at least 70% across all sleep stages, although accuracy and response rates decreased with the depth of the sleep stage. Interestingly, those who entered lucid REM sleep could explicitly recall performing tasks, whereas those who did not lucid dream were unable to. Responsiveness is also correlated with brain activity during sleep, a more complex brain state with faster brainwave oscillations prior to the verbal stimulation corresponded with higher response rates, which suggests that higher cognitive levels correspond with a greater ability to produce behavioral responses to external stimuli during sleep.

These results reveal that there exist transient windows during sleep in which humans can respond to external stimuli. Naccache explains “Our research has taught us that wakefulness and sleep are not stable states: on the contrary, we can describe them as a mosaic of conscious and seemingly unconscious moments.” This discovery opens doors to a variety of clinical applications and further research investigations. According to Oudiette, this could lead to the development of new sleep communication protocols, advancing research investigating sleep disorders or how brain activity during sleep impacts consciousness. Communicative windows could potentially be used to better treat sleep disorders, facilitate learning during sleep, or, excitingly, communicate with sleeping individuals during various sleep stages. Maybe someday you will be able to learn the answers to questions you have been dying to ask your partner or friends without them even knowing! These cutting-edge findings serve as the foundation for an entirely new way of studying and defining sleep, and will lead to exciting possibilities in the future.