For an animal missing both a heart and a brain, jellyfish are beautifully mystifying to watch as they glide through the water. As very simple creatures and extremely slow swimmers, jellyfish have been overlooked by many researchers when in fact the way in which they pulsate their bell to move is quite complex and efficient.

It was not until 2013 when Dr. Brad J. Gemmell and his research team at the Marine Biological Laboratory investigated the mechanics behind jellyfish propulsion through a unique form of passive energy recapture. For their study, Aurelia aurita, or moon jellyfish, known for their translucent, moon-shaped bell and short tentacles, were observed using computational fluid dynamics and pressure estimations through velocity measurements.

When the jellyfish contract their bell, they form two vortices. A high pressure vortex forms underneath while a low pressure vortex forms on the outer edges. As the bell bends, the high pressure vortex propels the jellyfish forward. This causes the low pressure vortex to roll beneath the bell, after which the water floods into this low pressure area, resulting in a secondary push, again propelling the jellyfish forward. This second boost requires zero extra energy since no muscle contraction is required, allowing the jellyfish to move 80 percent farther without any energy expense.

However, jellyfish are about 90 percent water and swim at a much slower rate compared to their fish counterparts. In order to accurately compare the energy expenditure between other aquatic creatures, Gemmell used the cost of transport analysis rather than the currently accepted calculation in order to account for net metabolic energy demand. Using this analysis method, moon jellyfish are calculated as 3.5 times more efficient than salmon, which was previously thought to have been the most powerful and efficient aquatic animal.

Using this analysis method, moon jellyfish are calculated as 3.5 times more efficient than salmon, which was previously thought to have been the most powerful and efficient aquatic animal.

The unique method of passive energy recapture used by jellyfish could further be studied and eventually implemented into biomimicry applications, including the design of ocean machines like autonomous underwater vehicles. By applying this jellyfish trick, the length of a possible deep sea expedition could increase by reducing energy consumption.

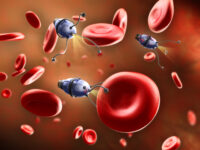

But more so, researchers at the California Institute of Technology and Stanford University used microelectronics to even further the efficiency of jellyfish. In a paper published at the beginning of 2020, moon jellyfish were given eight pacemakers placed along the nerve clusters on their bell in order to increase the frequency of bell contractions, which would hypothetically correlate to an increase in the swimming speed of the jellyfish.

They found that at a frequency of around 0.5 to 0.62 hertz, the swimming speed of the jellyfish was about 2.8 times greater than without the microelectronic attachment. Not only were the jellyfish able to swim faster but they were also more efficient than their usual swimming pace, becoming nearly three times faster after consuming only twice the energy. The goal of this study was to evaluate the possible energy savings for using jellyfish as a mode to discover more about the ocean. Current robots being deployed into the ocean for research purposes use up to 1,000 times more power than the jellyfish with the microelectronic attached. Natural jellyfish live in a wide variety of environments with a range of temperatures, salinity and oxygen levels, and other conditions that could be mapped out with the help of bionic ones.

With no harm coming to the jellyfish through the attachment of the microelectronics, the most efficient creatures in the ocean can be further powered for even higher efficiency. Although there still remains further developmental improvements and ethical questions in using and controlling jellyfish for research purposes, the possible implications could allow humans to explore the 90 percent of the ocean that still remains a mystery to this day. All in all, jellyfish are some of the coolest creatures in the ocean, and that’s a no brainer.

Science Advances (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz3194

PNAS (2013). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1306983110