Bill Wilson co-founded Alcoholics Anonymous in the 1930s. He had struggled with alcoholism since his early twenties and depression even longer. But while AA helped Wilson recover from alcoholism, he remained frustrated with available mental health treatments. So, in the ‘50s, he began collaborating with psychologist Betty Eisner and discovered the power of LSD. In a letter to science writer and philosopher Gerald Heard, he wrote, “I am certain that the LSD experience has helped me very much. I find myself with a heightened color perception and an appreciation of beauty almost destroyed by my years of depression … The sensation that the partition between ‘here’ and ‘there’ has become very thin is constantly with me.”

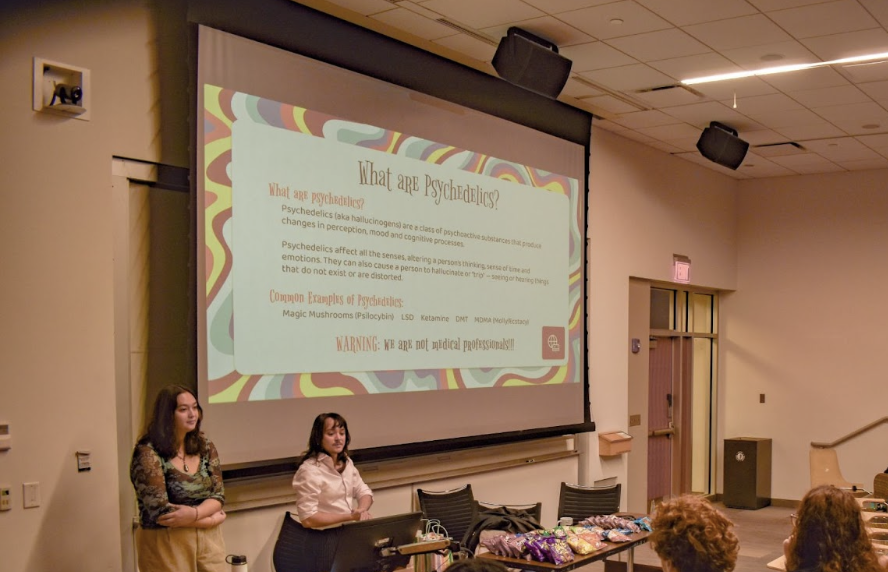

That era marked the beginning of the complicated modern history of psychedelics, mental health treatment in the U.S., and the science behind these substances. On Nov. 15, NU Sci and the Northeastern Psychedelics Club — NEU Psyches — hosted a meeting to explore this history. NEU Psyches e-board members, Camille Tosques and Indigo Zenobia, walked through an overview of psychedelics and their place in our healthcare system. NEU Psyches supports the spread of information, education, and research surrounding the history and practice of psychedelic substances, but does not suggest the use of drugs.

Popular psychedelics include psilocybin (magic mushrooms), LSD (acid), Ketamine, DMT, and MDMA (molly). Most psychedelic research is based on structure-activity relationship studies, which look at the chemical structure of the psychedelic and the biological response of compounds in the brain. While there is still a lot of research to be done, existing structure-activity studies have shown that psychedelics are agonists; they activate serotonin receptors in our brains. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter, a chemical that carries signals throughout the brain and body and encourages long-lasting happiness and well-being. By increasing serotonin reception, psychedelics promote neuroplasticity, a phenomenon that builds new connections between neurons.

Human beings tend to fall into patterns of behavior as a result of feedback loops. We form these loops throughout time as we react repeatedly to given stimuli. While some feedback loops can be incredibly beneficial to our health and wellness, such as the endorphin boost from exercising, others can become increasingly detrimental. For example, alcoholism is built from the feedback loop of drinking to alleviate the discomfort of a comedown or hangover from drinking initially. Many addictions are built off of these feedback loops, leading to habits that are overwhelming to our daily lives and challenging to break.

The use of psychedelics has had significant breakthroughs in the treatment of addiction via this ability to crack feedback loops. The boost of serotonin receptors directly targets the decreased serotonin levels typical of patients with substance use disorder, and therefore decreases the desire or need for the previously depended-upon substance. Studies have shown significant positive results for the use of psychedelics in the treatment of tramadol addiction in Central and South Africa, alcoholism, nicotine and tobacco addictions, and even gambling and sexual addictions. Instead of targeting symptoms and after-effects of substance abuse disorder, psychedelic treatments target the root cause, meaning that the results could be much more consistent and long-lasting.

Beyond addiction, there are a slew of mental health disorders that plague modern society. Anxiety, depression, PTSD, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, and OCD are all increasing in prevalence and our understanding and treatment of them are struggling to keep up. Official studies and testimonies from self-guided treatments report that the “change in perception” and the “conscious-altering” effects of psychedelics are incredibly effective at alleviating many symptoms and even the roots of these mental illnesses.

The most powerful tool of psychedelic treatment is ego dissolution, or the near physical separation of consciousness from the perception of a “self.” Subjects under the influence of psychedelics report the ability to objectively view their mental health struggles from the outside. Since many mental health disorders are overwhelmingly self-consuming, there is often an associated distortion of reality. Removing this distortion for individuals with mental health issues to view themselves as they truly are can have a profound impact on how they face mental health challenges. Individuals suffering from anxiety, particularly social anxiety, use ego dissolution to view themselves less critically and accept themselves as they accept those around them.

During the club discussion, Tosques and Zenobia spoke about the use of psychedelics to allow patients with depression to “realize that life is beautiful and worth living,” patients with OCD to “relinquish control” after tripping, and patients with PTSD to separate pain from traumatic emotional processing, allowing them to move forward with a better sense of closure. A slightly more niche use of psychedelics has been documented in terminal illness cases, allowing patients to remove the intense fear of death and accept the end of their lives with peace. In general, psychedelics “enable you to look at yourself with compassion,” Tosques said, which is a skill that many people, particularly young people in today’s world, really struggle with.

With so many studies and testimonies as to the effects of psychedelics, research into the physical effects is still emerging. The near-spiritual experiences of many frequent trippers (or psychonauts, as they call themselves) are often described as a heightened sense of consciousness and the ability to access new areas of their brains. We typically use the visual cortex, a section near the back of our brains, to perceive our environment. Recent scans of brains on various psychedelics revealed much more of the brain lit up, reflecting heightened and much less predictable brain activity. This explanation of increased variance in brain networking supports claims that psychedelics encourage neuroplasticity and habit-breaking.

“Psychedelics ‘enable you to look at yourself with compassion,’ Tosques said, which is a skill that many people, particularly young people in today’s world, really struggle with.”

University of Sussex professor Anil Seth describes the difference in consciousness levels as sleep states, waking states, and trip states. Brain imaging shows the absence of consciousness and brain activity during deep sleep, with almost no visible activity. Extensive imaging on sober waking states gives a solid baseline — around 30% of the brain — for how the majority of people typically operate.

Theories of consciousness indicate that human beings naturally limit our brain capacity to just below a critical level, allowing us to operate at what is known as secondary consciousness. This behavior is an evolutionary trait that limits our perception to focus on self-awareness, reality, organization, and careful decision-making. In doing so, we keep ourselves safe and reduce potentially dangerous fantasies or ideologies.

Primary consciousness, achieved under the influence of psychedelics, expands activity to typically dark areas of the brain, allowing trippers to come to out-of-the-box conclusions that are not influenced by the regular evidence-based feedback loops. Unpredictable conclusions are a result of a scrambling or disorganization of typical brain linkages and network patterns. Whereas normally our brain is grouped into functional groups that communicate very well within themselves, on psychedelics, sections of our brain are much more capable of breaking out of their groups and talking to each other.

This theory supports the explanations for the psychedelic treatment of mental health disorders. Take depression for example: Cognition in patients with depression is continually altered by an unyielding sense of pessimism. By scrambling these learned network connections linking pessimism to an individual’s predicted reality, suddenly pessimism affects a variable amount of their thoughts and decisions. The brain is then able to flex its secondary consciousness to reflect the experience during primary consciousness and reduce the impact of pessimism.

Despite all of the studies, testimonies, and groundbreaking research surrounding psychedelics and their incredible impacts on our cognition and health, there is still a great deal of stigma surrounding their use, decriminalization, and legalization. Many of society’s stigmas come from an association of substances with minority groups, similar to the association of marijuana with Black people in America. In the United States, the association of psychedelics with the hippie and counterculture movement of the 1960s followed by the War on Drugs movement in the early ‘70s has resulted in the negative connotation of psychedelics. This likely results from a misrepresentation of the counterculture movement, with much of today’s youth citing drugs as a main tenet of the hippie movement — when in reality the political demonstrations were of much more importance — and those who partook in drugs often getting called “freaks.”

“Despite all of the studies, testimonies, and groundbreaking research surrounding psychedelics and their incredible impacts on our cognition and health, there is still a great deal of stigma surrounding their use, decriminalization, and legalization.”

As with the slow decriminalization and legalization of marijuana, there is hope for the future of psychedelics in medicine and treatment plans. With continued education and research, we can come closer to reliable solutions for the countless members of society who suffer from mental health disorders. Interest groups like NEU Psyches, which is supported by Northeastern University, are making the topic less taboo and more accepted by the general public. If Bill Wilson was around to see this resurgence in psychedelic research, hopefully he would be excited and inspired by the potential for the widespread use of psychedelics in medicine.

- Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs (2017). DOI: 10.1007/7854_2017_475

- ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science (2021). DOI: 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00071

- Current Drug Abuse Reviews (2014). DOI: 10.2174/1874473708666150107120011

- Frontiers in Human Neuroscience (2014). DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

- Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy & Rehabilitation (2014). DOI: 10.4172/2324-9005.1000106