There’s a reason why some are naturally gifted artists and others are born mathematicians, some are social butterflies while others recharge with solitude, and some study using repetition while others can take a mental photo. When it comes to brain structure, everyone is different. An individual’s traits have much to do with upbringing, context, and life experiences, but strengths and weaknesses in specific areas of the brain can play a major role.

When it comes to dyslexia, scientists have been able to point to particular lobes to be its root cause.

Many think of dyslexia as writing and reading letters backward (e.g. P/9, was/saw), but the term hosts several characteristics that fall under the umbrella of reading difficulties including spelling, reading, and listening. Dyslexia is neurobiological by nature, meaning that it is due to imbalances in the brain. While every brain is different, particular traits cause dyslexia.

Structurally, the brain can be divided into two hemispheres, the left being more analytical and the right being more creative. From here, the brain is further segmented into lobes with particular responsibilities. One of these lobes, known as the left parietotemporal lobe, is involved with word analysis. Studies have found that people with dyslexia often have less matter in this lobe, leading to problems processing language at a normal pace.

Other studies have shown activation differences in the brain when comparing dyslexic and unimpaired individuals. For example, children without reading difficulties had strong activation of the left occipitotemporal lobe, which is responsible for rapid access to language. In the same study, researchers found that children with dyslexia compensated less activation in this area with stronger right-side activity.

People often characterize themselves as left- or right-sided, left-sided being more logical and right-sided being more creative. When it comes to those with dyslexia, individuals have the potential to be symmetrical due to compensation. This can contribute to many strengths that can be used in careers and beyond.

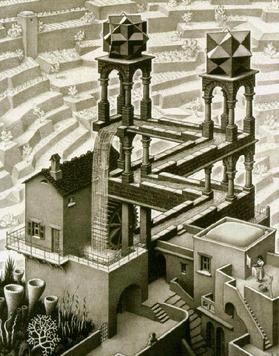

For example, have you ever seen an optical illusion that simply does not make sense? Take M.C. Escher’s Waterfall. The sketch depicts a waterfall running downhill along with the source. The artist also makes us look twice by playing games with levels, planes, and scales. Overall, the image goes against nearly every law of physics. These types of images are called “impossible figures,” and a study from the University of Wisconsin found that those with dyslexia were able to pick out impossible figures in seemingly normal pictures more often than those without reading disabilities.

It may seem puzzling that something thought of as a disability can contribute to major strengths, but these differences in brain activity may help explain why those like Thomas Edison, James Maxwell, Galileo Galilei, and Albert Einstein have been able to make incredible discoveries with lifelong reading challenges.

One benefit is that those impaired are more likely to see the bigger picture. Rather than zooming in on a tree, for example, they can see the whole forest. This can relate to the interconnectivity of anything from problem-solving to relationships; dyslexics can often see from multiple perspectives. As mentioned, finding the odd-one-out is another commonly enhanced skill, which can hugely benefit fields like science and astronomy. They can pick up on things that are out of place that may have gone unnoticed.

Individuals with dyslexia have a strong visual understanding, and some even have a photographic memory. Pattern recognition is another strength from identifying similarities across complex systems.

Spatial knowledge is an additional strength. Architect Richard Rogers and fashion designer Tommy Hilfiger both have had lifelong difficulties learning in a traditional environment but have gone on to be some of the best designers in their respective fields. This could even be extended to organic chemistry, engineering, and other fields where individuals need to think three-dimensionally.

Clearly, something seen as a disability can lead to many strengths that often go overlooked. Having dyslexia personally, I have had trouble with reading and spelling throughout my academic career.

This being said, my photographic memory has served me well; for example, I can travel somewhere once, go back five years later, and know my way around like a true local.

While brain structure may be atypical when compared to the average person, uniqueness can be used to make incredible discoveries, designs, and contributions to society. It begs the question of whether something should be considered a “disability” simply by going against the status quo.

Sources:

Sage Journals (2001). DOI: 10.2307/1511244

National Library of Medicine (2002). DOI: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01365-3

Brain and Language (2003). DOI: 10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00052-X