The logical basis of all computers can be traced back to the ingeniousness of one man: Alan Turing. Turing, born on June 23, 1912, grew up with a keen interest in using mathematics and logic to explain the world around him. He went on to study mathematics at King’s College and eventually joined the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. This would mark the beginning of Turing’s most notable achievement in world history and computer science.

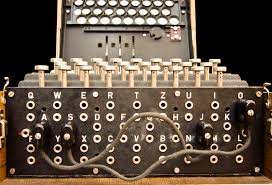

Around the time of the Second World War, the use of radio communication increased and allowed for efficient two-way transmission. To avoid interception and exposure, the German military encrypted these messages using a machine called the Enigma machine.

The machine had many components that contributed to the complex nature of the encryption process. The wires were mixed and matched by rotors so that a letter would enter as itself but leave as another letter. A single Enigma machine could also have multiple rotors connected side-by-side. This meant that letters could change multiple times. The machine also contained a plugboard, which swapped the letters in a reciprocal way. Each day, the Germans would be given a predetermined setting that told them how to orient the rotors and the plugboard so that they could decode the messages using an Enigma machine. However, without knowing these settings, it was almost impossible to figure out which combination out of the 158 trillion possibilities was the correct one.

In response to the perplexing conundrum, British Intelligence created a group of the top minds at Bletchley Park, among them Turing, to decode the signals.

Turing, rather than finding the correct code, deduced that it would be easier to eliminate the ones that were surely wrong. This would leave an increasingly smaller number of possible solutions, bettering the odds. He knew two things: a letter could not be coded as itself and two letters code for each other. He then used this knowledge and common German phrases (cribs) sent every day to crack the code. The cribs were usually German greetings or weather reports, so it was almost certain that they were in the message. The phrases were lined up with the encrypted message so that each letter aligned. Turing checked all of these pairs, and if there was a pair of letters that were the same, he knew that this orientation was incorrect. He would then shift the word one letter over so there would be new pairings, repeating this process. In the end, there would be many possible correct alignments, and Turing would have to test each alignment to find the correct one. Although logically sound, this method required meticulous work, so Turing created a machine, the Bombe, to do it for him.

However, without knowing these settings, it was almost impossible to figure out which combination out of the 158 trillion was the correct one.

In order for the machine to crack the code, it needed a template code: the crib message. Turing would create maps, or menus, that would show the connection between the letters in the given message.

By wiring the back of the Bombe to resemble the menu, a circuit could be formed to test which rotor settings produced a continuous electric signal. A comparator would essentially check for a complete circuit with that specific setting. If not, one of the rotors would click one notch, and the next setting would be checked. This continued until the comparator unit detected a complete circuit. At this point, the machine would stop, and the operator would read which settings the rotors were at to produce a successful circuit. Additionally, because the machine had a total of 36 sets of rotors, multiple settings could be checked simultaneously. This allowed the team at Bletchley Park to crack the daily Enigma code in under 20 minutes. Much of the code decrypted revealed integral information that saved thousands of lives and shortened the war by nearly two years.

Turing, rather than finding the correct code, deduced that it would be easier to eliminate the ones that were surely wrong.

While Turing contributed greatly to the final demise of the Axis powers and the greater world of computer science, his work remained unrecognized for many years. Even more unfortunate was the mistreatment he received by the law for being gay. Turing was forced to succumb to hormone treatment that was believed to change his sexuality. However, he still continued with his work, producing many more papers and theories in the field of mathematics and science. His work at Bletchley Park along with his many foundational theories prove his undoubted role as the catalyst for what is known as the odyssey of computer science.

Sources:

Cryptologia (1999). DOI: 10.1080/0161-119991887793