What comes to mind when you imagine an appetizing spread? Vivid colors, thoughtful plating, perhaps some steam rising off the table. Zoom out and think of some other components. Deep aromas fill the room, perhaps with some ambient music and light chatter. Are you enjoying this meal with family and friends? Or are you eating alone and reflecting after a long day? Through curation of a carefully-tuned combination of all of these stimuli, plus the story and characters that experience them, director Hayao Miyazaki manages to imbue meaning into every meal depicted in his movies.

Miyazaki’s most famous work has come out of Studio Ghibli, an internationally-recognized, Japanese animation giant. Miyazaki, along with co founders Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki, founded Studio Ghibli in 1985 and have continued to crank out legendary films ever since. The first Ghibli film that I can recall watching was “Ponyo,” a 2008 movie about the friendship shared between a magical goldfish and a human boy. After the movie’s heartwarming storyline, stunning imagery, and lovable characters, what impacted me most were its renderings of food. After watching a handful of other Miyazaki works, coming to college, and comparing notes with other fans, I’ve found that his culinary eye and ear make for scientifically-optimal cinema.

Animation’s inherent malleability when it comes to imagery and sound lends itself to psychological satisfaction.

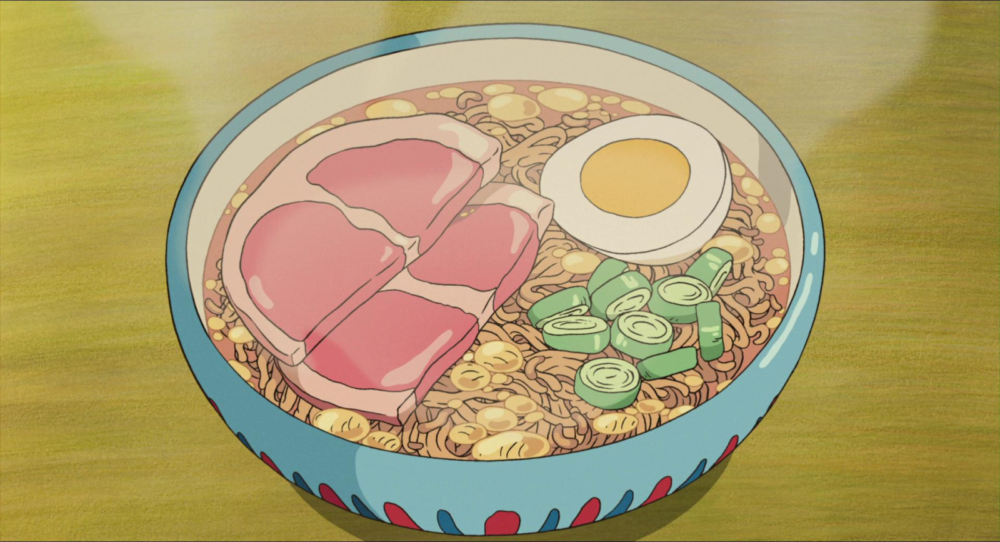

Animation’s inherent malleability when it comes to imagery and sound lends itself to psychological satisfaction. In a 2016 study geared toward comparing the modern human’s preferences when visually evaluating food, participants were shown a variety of food and non-food images, then asked to rate how appetizing they found each image. The results demonstrated a positive correlation between an increase in red-brightness and appetite, and a negative correlation between increasing green tones and interest. Subsequently, Studio Ghibli artists play into human evolutionary desires by tailoring their color palette toward warm tones and away from greens and cooler colors. This preference can be traced back to our roots as a hunter-gatherer society, and even further back to our living and extinct primate relatives who depended on trichromatic vision to detect the ripest and most nutritious fruits, which are usually more red-tinted and vivid than their unripened counterparts. The arrangement and plating of Ghibli meals is also conducive to a pleasant reception. The two-dimensional nature of this kind of animation requires food to be arrayed in a horizontal plane, which a 2018 study on food presentation confirmed to positively influence consumer interest, willingness-to-pay, and perception of portion size.

Encompassed within the food-centric scenes Miyazaki purposefully includes in many of his films is the preparation of the meal. Miyazaki enhances this otherwise mundane process through the fluid movement of the home cook, and most effectively, the sounds that come along with the act of cooking. This is especially evident in a scene from “Ponyo” where the mother of one of the protagonists prepares a hearty bowl of ramen. A storm is raging outside, yet tones of soothing music layered over bok choy being pushed into a boiling pot of broth make it seem like everything is as it should be. A study conducted in 2010 concerning the effects of ambient restaurant noise and music affirms the therapeutic effect that this scene has on viewers. The increase in noisy, crowded establishments pushed researchers to ask participants to sample salty and sweet foods when placed in loud environments (upwards of 70 decibels) and quiet environments (under 60 dB) and report back the “sensory-discriminative qualities of the gustatory stimuli” in each scenario. Subjects reported back that the loud background noise dampened the sweetness and saltiness of biscuits and potato chips respectively, demonstrating the influence that one’s surroundings has on taste experience, and explaining the positive effect that light music and calming sounds have on filmgoers.

The characters’ satiated verbal and nonverbal responses to enjoying the meal and being with loved ones are the proverbial cherry on top of Miyazaki’s multisensory experience.

The last component that Miyazaki includes seals the deal: the people that the food is enjoyed with! Many of the scenes highlighting a meal have a unifying or comforting purpose, with family and friendship being heavily emphasized during that moment. The characters’ satiated verbal and nonverbal responses to enjoying the meal and being with loved ones are the proverbial cherry on top of Miyazaki’s multisensory experience. While only being able to reach viewers through sight and sound, his work manages to warm all five senses, plus, if you believe in it, the soul.

Scientific Reports (2016) DOI: 10.1038/srep37034

Appetite (2018) DOI: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.06.005

Flavour (2014) DOI: 10.1186/2044-7248-3-9