Can you imagine never sleeping again? We often underestimate the importance of sleep; by some estimates, college students in America get an average of 6 hours of sleep per night, as opposed to the suggested 8-10 hours. Getting enough sleep is extremely important — it gives the brain time to consolidate memories and new information, and leaves you well-rested in the morning. However, for the rare few suffering from fatal familial insomnia, the progressive loss of sleep can lead to a painful and tragic end.

According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), fatal familial insomnia is designated as an extremely rare genetic disorder, affecting approximately one in a million people each year. According to the NIH, after symptoms begin to show, fatal familial insomnia leads to death in about 6-36 months. As of right now, only 70 families are known to have the disorder.

According to the NIH, after symptoms begin to show, fatal familial insomnia leads to death in about 6-36 months.

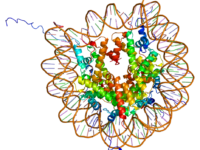

Fatal familial insomnia is a prion disease, meaning that its cause can be linked to an unusual variant of the prion-related protein gene, abbreviated as PRPN. The variant version of this protein makes the affected individual’s body produce misfolded versions of the human prion protein and accumulate in the brain over time. While it is possible for a spontaneous mutation in the PRPN gene to occur and cause fatal familial insomnia in an individual with no family history of the disorder, most cases are inherited from one’s own parents. Specifically, fatal familial insomnia follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning that only one parent needs to have the disorder for there to be a high likelihood that it will be passed down to their children. A diagnosis of this disorder can be verified by genetic testing for mutations in the PRPN gene, or through other clinical testing such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans, which can detect abnormalities in the brain related to the disorder’s presentation.

Misfolded prion proteins are known to be quite toxic, and as they accumulate — specifically, in the thalamus of the brain, a region whose main function in the relay of signals (sensory or motor) and the regulation of alertness and conscious thought — are accompanied by a plethora of detrimental symptoms. The condition has a long incubation period as the body makes these misfolded prions, but once levels of such prions hit a critical level, the clinical presentation of the disease is quite short. Fatal familial insomnia is a neurodegenerative disease, which as the name suggests, is characterized by progressive insomnia which worsens over time caused by damage to and the death of neurons in the brain.

The condition has a long incubation period as the body makes these misfolded prions, but once levels of such prions hit a critical level, the clinical presentation of the disease is quite short.

People affected by the disorder may initially have mild symptoms, such as issues with concentration, speech problems, confusion, or inattention. Some will also exhibit abnormal movement of the eyes, double vision, swallowing problems, muscle spasms or tremors, or other symptoms which are similar to Parkinson’s Disease. As time goes on, the autonomic nervous system may be affected as well, leading to varying symptoms including but not limited to hypertension, tachycardia, and fevers. These symptoms may also be accompanied by depression or anxiety. Ultimately, people affected by fatal familial insomnia fall into a coma and, as the name suggests, will eventually die.

As of right now, there is no cure for fatal familial insomnia. While this is certainly a grim outlook for the few affected by the disorder, some treatment options do exist. Treatment is currently aimed at managing the specific symptoms which vary in each patient, a comprehensive process which involves the joint-efforts of neurology and psychology teams. For example, if a patient begins having seizures, they may be prescribed anti-epileptic medications. Similarly, if they are exhibiting muscle spasms, known clinically as myoclonus, they may be treated with clonazepam, a sedative which relaxes the spasming muscles. Patients with fatal familial insomnia may also be advised to stop taking any medications with memory-related side effects, or those which unintendedly may worsen insomnia. Due to the heritable nature of the condition, family genetic counseling and the implementation of psychological support systems is recommended as well.

Image Source: Flickr