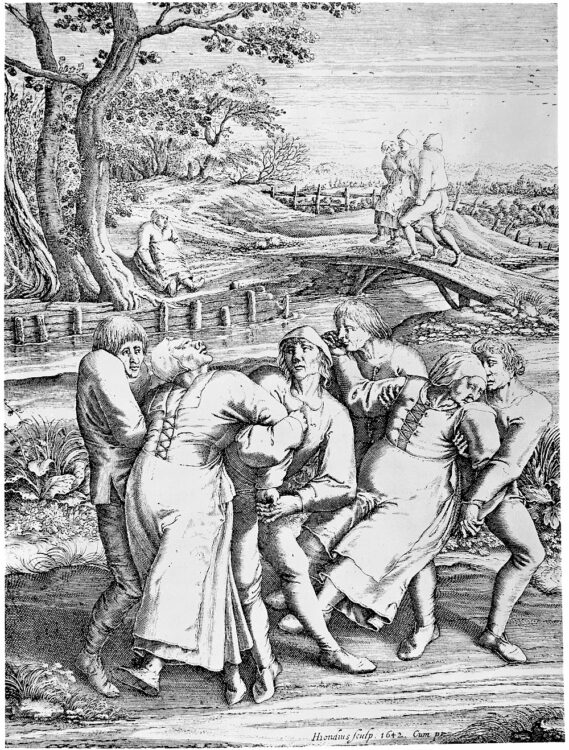

In the autumn of 1518, Strasbourg, a prominent trading city on the banks of the Rhine River, was alive with the sound of dancing. Musicians played day and night; a new stage was constructed across from the market; and over 400 people — all stricken by the dancing mania plaguing the city — whirled, twirled, and waltzed uncontrollably, some screaming in pain, pleading for help, or having terrible visions. At the height of the chaos, allegedly, up to 15 people died each day because of the compulsion to dance, making it the largest outbreak of the dancing plague in European history, with several smaller instances recorded in the 16th and 17th centuries but stopping around the turn of the 18th century.

…over 400 people — all stricken by the dancing mania plaguing the city — whirled, twirled, and waltzed uncontrollably … At the height of the chaos, allegedly, up to 15 people died each day because of the compulsion to dance…

Though it was the largest, the 1518 Strasbourg outbreak was far from the first. Numerous medieval sources corroborate a wave of dancing mania that ravaged western Europe in 1374 and smaller local outbreaks in 1247 and the early 15th century. The earliest purported outbreak was in Kölbigk (modern-day Saxony-Anhalt), where 18 people were cursed by a priest to dance for a year straight because of their impiety. However, there is still debate whether that story is a heavily embellished real event or simply folklore.

There are some similarities across the outbreaks. First, the dancers appeared to be in some kind of altered state, indicated by their inhuman levels of endurance, ignoring sore limbs and bloody feet, and crying about terrifying visions. Furthermore, all recorded outbreaks, save at Kölbigk, happened near the Moselle and Rhine, many times in places that had previous dance epidemics. Finally, the most common remedy was for the dancers to pray to saints associated with dancing, primarily Saint Vitus and Saint John, which for the most part worked; the Strasbourg outbreak ended after the ill were sent to pray at the shrine to Saint Vitus in the Vosges Mountains.

Most researchers say that the dancing plague was a mass sociogenic illness (a mass hysteria). Psychologically, a mass hysteria is defined by the rapid spread of the false perception of having an illness through a cohesive group where the belief stems from a nervous system disturbance with no underlying physical cause. Typically, mass sociogenic illnesses spread through social channels, with the affliction spreading to those who can see or hear those already infected; this spread is especially effective when people of lower status see those of higher status displaying symptoms.

Most researchers say that the dancing plague was a mass sociogenic illness (a mass hysteria).

The symptoms of any mass sociogenic illness outbreak follow the common expectations and fears of the affected community; the symptoms people display conform to cultural expectations. The citizens of Strasbourg had the recent cultural memory of past dancing outbreaks from nearby towns in the region, and with the widespread worship of Saint Vitus in the area, it explains the geographic distribution of the mania and why praying to the saints remedied the outbreaks. They believed that praying at his shrines could appease an angry Saint Vitus, who sent a dancing curse, and convince him to cure the afflicted. And for many psychosomatic illnesses, one only needs to believe a cure will work for it to do so.

Finally, to address the scale of some outbreaks, it’s important to consider some factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing psychogenic illnesses. Psychological stress, nutritional deficits in either macronutrients (calories) or micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), and seeing other people experiencing a psychogenic illness are all risk factors — all of which were common in the lives of medieval and early-modern peasants, increasing their susceptibility of experiencing a mass hysteria.

A myriad of circumstances at the time created the perfect storm for some of these outbreaks. Before 1374, a massive flood on the Rhine and Moselle ravaged whole fields of crops. Similarly, in 1517, the area around Strasbourg suffered from a massive famine, disease outbreak, and series of failed rebellions against landlords and clergy members. Furthermore, in all cases, as a psychogenic illness, when dancing mania outbreaks got bigger it made them more visible and more likely to grow. For example, the Strasbourg outbreak proliferated because, to combat the outbreak, city leaders originally prescribed more dancing, constructing a stage for the dancers, and hiring musicians to play day and night, only increasing the visibility of the dancers and thus the community spread.

Overall, with the stressors of such turbulent times, combined with the memories and sights of the dancing mania, it’s no wonder that some people slipped into a panicked state and experienced one of the strangest epidemics in recorded history.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons