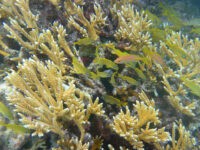

In the summer of 2021, a group of snorkelers accidentally discovered one of the oldest and largest coral colonies in the world. Located off of the coast of Golboodi, one of many Palm Islands in Queensland, Australia, this coral was named Muga dhambi, which means “big coral” in the language of the indigenous Manbarra people. This carousel-sized coral stands over seventeen feet tall and thirty-four feet wide, making it the sixth-tallest known coral in the Great Barrier Reef system. According to Australian biologists, this coral colony is estimated to be 421 to 438 years old, making it older than the United States. This age indicates that the colony was able to survive centuries of coral bleaching events, natural disasters, invasive species, and erosion.

This coral colony is estimated to be 421 to 438 years old, making it older than the United States.

Coral belongs to the kingdom Animalia and the phylum Cnidaria, meaning that they are closely related to jellyfish and sea anemones. They are colonial animals that connect themselves by building a calcium carbonate skeleton made from elements in surrounding seawater. Coral polyps are small, soft-bodied parts of the animal and bring in ion-rich seawater. They absorb the calcium ions in the seawater and then apply them to the surface of their existing skeletons. The corals then pump hydrogen ions from the water out of the calcifying space between their cells, which produce more carbonate ions that bond with the calcium ions to form calcium carbonate. This process continuously repeats itself as long as the coral is healthy enough to survive. Massive coral colonies, such as Muga dhambi, tend to prioritize width over height to sustain greater stability in the water.

Given that Muga dhambi isn’t even the largest known porite (a coral genus) in the world, there is a possibility that even larger porite colonies can exist elsewhere on the Great Barrier Reef. This discovery gives us hope for the future of our marine ecosystems. If our oceans are still able to sustain coral colonies of this size, that means that the planet has not hit the tipping point of extinction and still has time to make a recovery. However, coral are some of the most vulnerable species to the effects of climate change, as the chemical reactions that take place in the calcium carbonate building blocks of the skeleton partially depend on the acidity of ocean water. The average pH of seawater is 8.1, but as atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide continue to increase, more carbon is sequestered into oceans in the form of carbonic acid, thus lowering the pH level. For every one pH unit decrease, there is a ten-fold increase in acidity. This carbon absorption causes chemical reactions in the water that produce more bicarbonate ions and less essential carbonate ions for corals. This change in pH prevents the coral colony from building and repairing its skeleton, leaving it vulnerable to erosion and natural disasters.

If our oceans are still able to sustain coral colonies of this size, that means that the planet has not hit the tipping point of extinction and still has time to make a recovery.

The rise in ocean temperatures is another impact of climate change that threatens the health of coral and their associated ecosystems. The average global ocean temperature has increased by about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit since 1901 and has been consistently higher during the last thirty years than at any other recorded time period. To obtain energy, corals have formed a symbiotic relationship with a species of photosynthetic algae called Zooxanthellae. This alga grows in the tissues of the coral, but once the water temperature gets too warm, it gets expelled, causing the coral to turn white. The bleached coral is not dead — it is just under more stress and is more susceptible to death, which usually comes about if conditions do not return to equilibrium. Furthermore, Nathan Cook, a marine scientist at Reef Ecologic, reports “a decline of 50 percent of coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef over the past 30 years” in a post on The Australian Institute of Marine Science’s website. This change is proceeding at an alarming rate, but there are still resilient coral colonies — such as the Muga dhambi — that could survive in the future. There is still time to turn things around for the rest of the corals, given that there is sometimes a twenty-year recovery period after initial bleaching. Human sustainability and conservation efforts must continue to be enforced and employed for years to come, and, hopefully, we can foster a world filled with countless massive coral colonies.

For further reading:

- https://www.sciencetimes.com/articles/32982/20210821/largest-coral-muga-dhambi-discovered-goolboodi-great-barrier-reef.htm

- https://www.livescience.com/massive-400-year-old-coral-great-barrier-reef.html

- https://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/how-do-corals-build-their-skeletons/

- https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coral_bleach.html

- https://www.neefusa.org/nature/water/warming-ocean