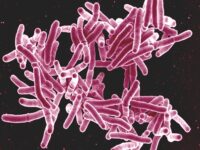

Extremophiles are microorganisms that survive — and thrive — in extreme conditions not considered suitable for other forms of life. This umbrella term encompasses bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi with unique adaptations allowing them to inhabit extreme temperature, radiation, salinity, pH, and other physical and geochemical conditions. Extremophiles can be found in deep-sea hydrothermal vents near underwater volcanoes, the sulfur springs of Yellowstone National Park, and the cold, arid landscape of Antarctica. These microbes have intrigued NASA scientists and cultural anthropologists, who are curious about what their ability to survive in unusual terrestrial habitats means for the study of alien life.

Extremophile bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi are categorized based on their adaptations to specific environmental conditions. Thermophiles, or microbes that thrive in high temperatures, have plasma membranes that contain unusual lipids that can tolerate high temperatures. Alkaliphiles, named for their adaptation to basic conditions, have cell membranes with particular mechanisms that ensure a homeostatic internal pH regardless of their environment’s unstable pH. Cold-loving psychrophiles utilize antifreeze proteins to carry out cellular activities despite the low thermal energy and high viscosity of their environmental solution. Just as the conditions of extreme environments vary, so do the adaptations of extremophiles.

Extremophiles are described by Massachusetts Institute of Technology cultural anthropologists “as analogs of early one-celled earthlings, ancestors of all life, and also as possible pointers to what life might look like on remote worlds

Extremophiles have taken center stage in the realm of astrobiology, which is defined by NASA geochemists as “the study of the origin and evolution of life in a cosmic context.” Astrobiology originated during the Cold War and the Space Age when NASA was concerned about the potential need to develop defenses against extraterrestrial contaminants. Though the “grand American frontiering narratives” from the 1960s have faded, research on extremophiles in subsequent decades has sparked new speculation about the definition of habitable environments. Extremophiles are described by Massachusetts Institute of Technology cultural anthropologists “as analogs of early one-celled earthlings, ancestors of all life, and also as possible pointers to what life might look like on remote worlds, perhaps in alien oceans on Jupiter’s moon Europa or on Saturn’s Enceladus.” The scientific conversations around extraterrestrial life have made a fascinating shift from discovering distant civilizations and cultures to the nature of microscopic organisms.

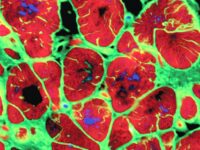

However, even the most extremophilic organisms can be limited by certain conditions. A more recent 2021 study of extremophiles and microbial habitability in Antarctic soil may have altered the research trajectory on alien microbes. Much to their surprise, geoscientists from the University of Colorado Boulder did not detect microbes in around 20 percent of 204 samples of ice-free soil. Their results suggest a combination of cold, dry, and salty conditions at the inland and high elevations of the Transantarctic Mountains is perhaps one too many extreme conditions to support microbial life, even by extremophile standards.

These scientists are also careful to note that although they were unable to detect life in their samples, this finding does not prove the soils were naturally sterile as there is always another experiment or method that may lead to different conclusions. This distinction highlights the challenge of proving a negative result – no measurement or method of data collection is perfectly sensitive, and even the best experiment may not detect the presence of microbial life.

The findings from Antarctic soil illuminate two challenges in studying potential alien life. First, extremophile microbes, once thought to be a more likely form of alien life, may not exist under some conditions. The limit to the adaptability and resiliency of extremophiles suggests thermoacidophiles and alkaliphiles may be more earthly than alien. Second, proving negative results is just as tricky as proving positive results. While confirming the existence of alien life has been a challenge, disproving alien life also remains ambiguous. Scientists are far from confirmation or denial of extraterrestrial life, and the complexities and nuances of astrobiology make their studies all the more intriguing.

Social Studies of Science (2013). DOI: 10.1177/2F0306312713505003

Grand Challenges in Biology and Biotechnology (2016). DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-13521-2_1

Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences (2021). DOI: 10.1029/2020JG006052