While clouds rolling in on a sunny summer day may be a disappointing sight for many, clouds play a critical role in regulating Earth’s climate. A key gas produced by marine microalgae, known as dimethyl sulfide (DMS), is largely responsible for cloud formation. DMS is not widely known, but its characteristic “smell of the ocean” is unmistakable along beaches and coasts.

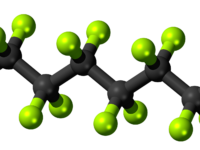

DMS is released through the breakdown of a compound known as dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), produced by phytoplankton. These tiny microalgae are equipped with enzymes called lyases that pull DMSP apart, emitting nearly 28 million tons of DMS each year. Upon entering the atmosphere, DMS is oxidized into sulfuric acid, generating aerosols that serve as cloud condensation nuclei. Sulfate aerosols provide a surface for water molecules to condense onto, allowing clouds to form. Clouds generally have a global cooling effect, reflecting shortwave radiation back into space.

As atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rise and the oceans subsequently grow more acidic, DMS production will be impacted. The enzyme system responsible for the breakdown of DMSP into DMS is extremely vulnerable to acidic conditions. Emiliania huxleyi, a microalgae species known as a coccolithophore, exhibited decreased DMS concentrations of 20% under elevated carbon dioxide conditions. Certain DMS-producing microalgae, such as coccolithophores, are also vulnerable to acidification, potentially changing the proportion of species in the phytoplankton community, and impacting total DMS production.

Junri Zhao and a team of researchers at the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Particle Pollution and Prevention have modeled potential changes in DMS in response to acidification on a global scale, and the subsequent impact on Earth’s radiative budget. From 2024 to 2099, the models project an average decrease of 13.3% in DMS concentration globally, and in response, an average decrease of 16.4% in direct radiative forcing. This highlights the role of DMS in regulating Earth’s energy balance by influencing the reflection of radiation back into space. Reduced cloud formation increases solar radiation which will accelerate summer melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet, and decreased precipitation could heighten the risk of droughts in some regions.

“Many climate models do not account for projected changes in DMS from acidification, but including DMS as a factor in climate change is critical to accurately predict future warming.”

Beyond its global atmospheric climate impact, reductions in DMS emissions will disrupt marine ecosystems. DMS is released as a chemical defense when zooplankton are grazing on phytoplankton. Larger predators including whales and penguins sense this release of DMS and utilize it to locate prey-rich areas when foraging. Decreased DMS could impair foraging efficiency and alter marine food webs.

Given the significance of DMS in climate regulation, iron fertilization has been explored as a potential geoengineering solution to climate change. Artificially adding iron to the ocean stimulates phytoplankton growth and has been shown to increase DMS emissions over a short-term scale, promoting cloud formation and cooling. However, iron fertilization could cause unintended ecological and biogeochemical disruptions, and the long-term impact on DMS is still unclear.

Many climate models do not account for projected changes in DMS from acidification, but including DMS as a factor in climate change is critical to accurately predict future warming. Ocean acidification may bring more blue skies and sunny days in the future, but clouds are essential in keeping temperatures balanced.