“Just relax your arm,” the nursing student from Northeastern University said calmly as she administered the vaccine into my arm. A million thoughts rushed through my mind as I sat in the chair. What if I have an allergic reaction? How sick will I become? Luckily, no major symptoms arose after the initial injection, and I finished the day attending online classes much like many other students during this pandemic.

Because I volunteer weekly at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to assist with patient care, I was eligible to get the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine from Northeastern as part of the movement to #VaxthePack. However, there is a lot of misinformation, and more importantly uncertainty, surrounding what the vaccines entail. One of the uncertainties is the differences between the newly-developed mRNA vaccine and the commonly used DNA vaccine.

The key objective of a successful vaccine is to create antibodies so that, if the infection enters the body, the body has an immune defense primed to attack the infection.

A million thoughts rushed through my mind as I sat in the chair. What if I have an allergic reaction? How sick will I become?

What is a DNA Vaccine?

The initialism, DNA, refers to deoxyribonucleic acid. On a molecular level, the prefix “deoxy” indicates only one hydroxyl group (OH–) on the pentose sugar of the molecule. DNA is the blueprint for life from which the body receives instructions to function. Moreover, DNA is very stable due to its double-stranded helical shape and contains genetic material that is essential for human survival.

DNA vaccines are the main type of vaccine used in the healthcare industry. Since DNA is the “blueprint for life,” these genetic instructions can be manipulated to protect the body from infectious diseases. The mechanism of the DNA vaccine is to inject a plasmid into the cell. A plasmid is a circular strand of DNA that exists in bacteria, but that is also used in laboratories to study genetics. This plasmid contains a DNA sequence that creates antigens, which prompt the body to fight the antigens by producing antibodies. Antigens act as foreign material in the body, which prompts the immune system to destroy these invaders. The body uses antibodies, also part of the lymphatic system, to fight the viral infection.

The key objective of a successful vaccine is to create antibodies so that, if the infection enters the body, the body has an immune defense primed to attack the infection.

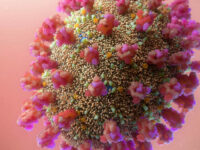

What is an mRNA Vaccine?

The initialism, RNA, refers to ribonucleic acid. On a molecular level, there are two hydroxyl groups (OH–) on the sugar of the molecule. RNA accelerates reactions by catalyzing enzymatic processes and is involved with the synthesis of important proteins. However, compared to DNA, RNA is single-stranded and therefore more unstable.

Though RNA vaccines are a new type of biotechnology, the logic of the vaccine mechanism is quite simple. In this case, mRNA, which refers to messenger RNA, transcribes genetic material into proteins. In the mRNA vaccine, the genetic material has information to create a COVID-19 “spike” protein. Once the spike protein is created, it becomes a foreign target of the immune system. The body forms antibodies to protect itself from the foreign spike protein. This method of preemptively creating antibodies requires a few more steps on a molecular level compared to the DNA vaccine, but still produces the same result.

Though the mechanisms and logic of RNA vaccines are increasingly evident to the scientific community and general population, an important aspect of scientific advancements is the comprehension of the constraints and limitations of results and products.

One of the limitations found with the vaccines concerns the question of how long the antibodies will last as experts are still unsure of the lifespan of the antibodies. This raises the question of whether or not people will need to get vaccinated more frequently for the sake of maintaining sufficient antibody levels. Although there is uncertainty, there are many checkpoints and regulations for vaccine development to ensure safe vaccine development. To trust scientific discoveries, and understand general molecular biology, is the key to pushing toward “herd immunity.”

Journal of Internal Medicine (2003). DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01140.x

Nature reviews. Drug discovery (2018). DOI: 10.1038/nrd.2017.243