A mosquito bites you — it’s annoying, but your skin doesn’t itch for long. You break your arm, but, in a few months, you’re fully recovered. These situations aren’t pleasant, but at least they are temporary. For some people with conditions like eczema and rheumatoid arthritis, pain and itch are a recurring part of their life. These symptoms can be debilitating, but scientists are working to find out more about the significance of pain and itching.

Associate professor of immunobiology Isaac Chiu and his lab members made an appearance at Trident Booksellers and Café on March 12 to discuss their research on itch and pain. This was one of Harvard’s Science by the Pint events, meant to improve the accessibility of scientific research for the local community, according to co-director Kaitlin Rhee.

“Associate professor of immunobiology Isaac Chiu and his lab members made an appearance at Trident Booksellers and Café on March 12 to discuss their research on itch and pain. “

Chiu opened by pointing out the function and importance of sensory neurons. They signal us to itch or experience pain, making us aware of sensations like pressure, heat, and chemical stimuli in order to ultimately protect us. Scientists believe that itch and pain have their roots as defense mechanisms, but there is still a lack of knowledge about their underlying mechanisms and pathways. Being closely related, pain relieves an itch while itch-reducers increase pain.

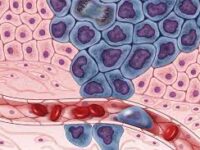

The Harvard immunologist explained that skin, or the dermis, is the body’s first line of defense against disease. As the protective layer that our body is coated in, any disruption to it warns people that something is amiss. It can be as simple as an insect bite or a symptom of a greater issue, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a type of neurodegenerative disease.

Immune and nervous system research often correlates to bigger issues, such as food allergies. Currently, there is no proven way to prevent the development of allergies, which affect 8% of children and 4% of adults.

“Neurons can make immune cells more inflammatory, inducing more inflammation and diseases, or they can dampen their effect. We want to figure out how the sensory neurons that Dr. Chiu mentioned [play a] role in food allergies,” said postdoctoral researcher Antonia Wallrapp, Chiu’s lab member.

Chiu and his lab also want to understand how the immune systems of those afflicted with disease can cause chronic pain. He pointed to the opioid epidemic as an example. “In terms of pain as a societal issue, there’s a huge need for better treatments for pain. The problem is that opioids are addictive … lots of side effects,” he said. “But can we find an analgesic that doesn’t have off-target effects?” In the future, the goal would be to make an impact on a disease or condition that affects the immune and nervous systems in Chiu’s perspective.

Nicole Almanzar, a PhD student at Chiu’s lab, brought up the social disparities that are seen with pain. “We know that diseases are not distributed equally. Looking at the impact of environmental exposures and [biology] helps us understand why specific groups of people present with more symptoms,” Almanzar said.

Even though itch and pain are closely related, itch is unique because, unlike pain, touching the irritated area provides relief. Adding to his statement, postdoctoral researcher, Liwen Deng, said “microbes that live on your skin can cause you to scratch. It impacts inflammation of the skin too.”

In response to a question asking whether stress could exacerbate itch and pain, Chiu posited that it is likely, but there may be many causes of itch that are not allergies. “There are still a lot of unknowns, scientifically, about what triggers itch and how to target it,” he said.

Still, he is hopeful for future advancements. His team has already discovered the complexities of neuro-immune crosstalk. In a study that tested on mice, they found using opioids to block pain signals resulted in less gray hair, meaning that itch and pain goes beyond the surface level.

Chiu ended the talk by saying his lab’s next big step would be to partner with a pharmaceutical company, which would allow their research to be reflected in the real world.

Robert Lamarre and his partner attended the event because of their curiosity on the topic and their love of science. With limited knowledge on itch and pain, he learned a lot from the event.

“There’s more to it than I thought,” said attendee Robert Lamarre.