Marine scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have discovered the largest known deep-sea coral reef in the world. This cold-water reef located off the Atlantic coast of the United States spans from Florida to South Carolina. This totals to a length of around 310 miles and is equivalent to three times the size of Yellowstone National Park, according to the finished maps.

“[The cold-water reef] totals to a length of around 310 miles and is equivalent to three times the size of Yellowstone National Park.”

The scientists, led by Derek Sowers, Mapping Operations Manager for the Ocean Exploration Trust, located the reef after an effort to map more of the United States’ coastline and marine structures. They hoped that knowing what lies off the coast would help them better understand and protect deep-sea marine life, since few researchers have previously explored the ocean’s depths. They focused part of this mapping effort on gathering more information on the Blake Plateau, a flat, elevated area covering the deep-sea ocean floor from Florida to South Carolina, since many believed it to be full of previously unstudied reef systems. Once they began exploring, the scientists quickly realized that its sheer size was unique from any other previously documented cold-water reef.

“The scientists quickly realized that its sheer size was unique to any other previously documented cold-water reef.”

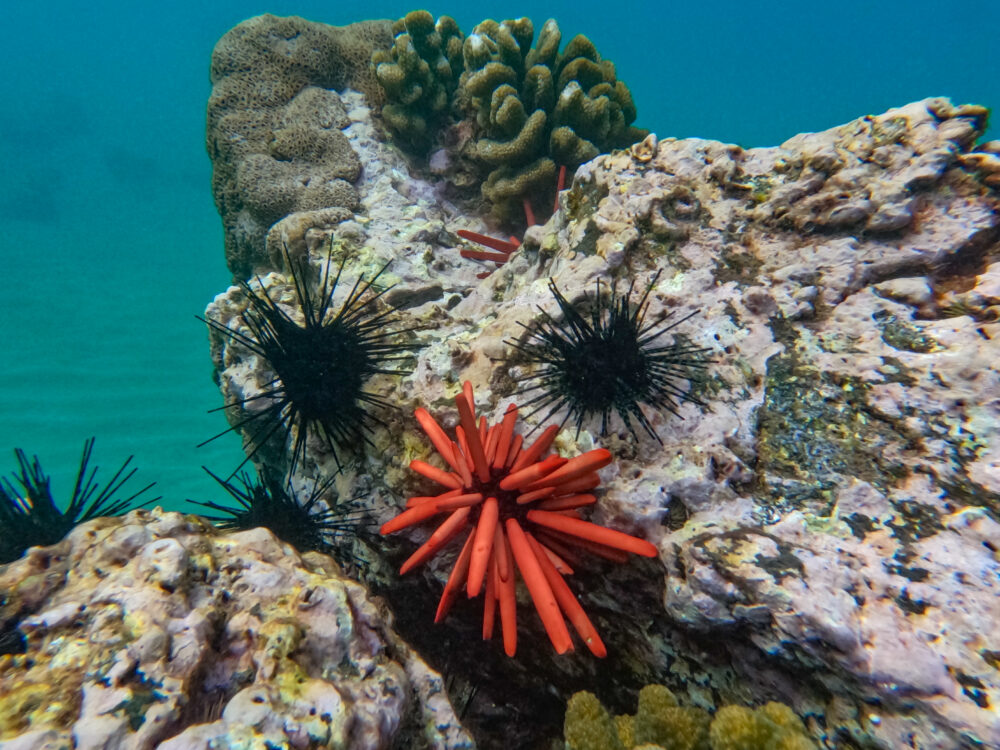

There are many similarities between the two known types of coral reefs (cold and warm-water reefs), with one of them being that the coral living within them largely determines their structures. Coral provides the foundation on which these ecosystems grow, since many different species depend on it for food, shelter, and general ecosystemic support.

However, cold-water corals (CWCs) differ in some ways from their warm-water counterparts. For example, deep-sea reefs rarely come into contact with sunlight due to their depth. Harsher conditions of the deep cannot support typical algae-reliant feeding as they do for warm-water corals, which forces deep-sea reefs to sustain themselves through filter-feeding particles. Due to the nature of their conditions, cold-water corals also tend to be more fragile and susceptible to breakage. However, they can support structures not seen in warm-water reefs, such as lengths of coral growing up instead of out. This unusual behavior might be attributed to the open space the deep sea offers in contrast to the more densely occupied shallow waters in which warm-water reefs thrive.

These initial findings in the cold-water reef in the Blake Plateau can support future endeavors by scientists trying to better understand cold-water environments and how to protect these reefs. Worldwide, coral reefs, especially warm-water reefs, are threatened by the changing climate, and scientists hope to understand more of the behavior of the CWCs in order to better conserve them. By understanding unique habits, like that of the upwards-growing coral in the Blake Plateau, scientists can plan ways to help them avoid threats of the human world.

The Blake Plateau CWC is only one example of the new discoveries scientists may make if scientists continue efforts to explore and research the depths of the oceans. Further mapping of the deep sea will uncover even more information about marine structures and wildlife and expand scientists’ knowledge of one of the most uncharted ecosystems on the planet, deepening our overall understanding of how the world works.