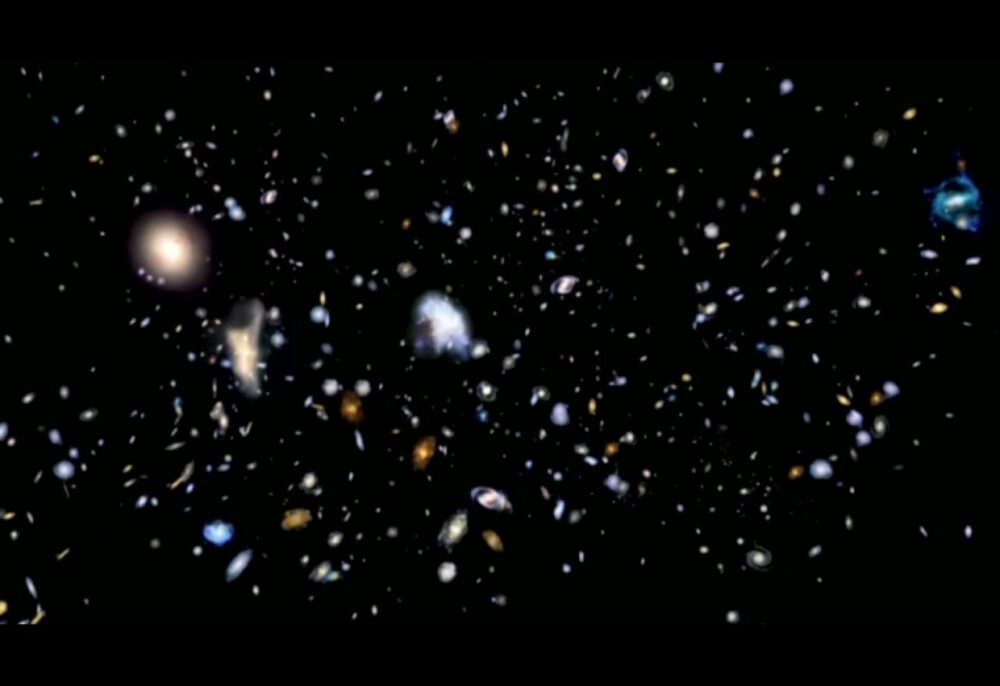

The universe’s expansion is one of the most profound and mysterious phenomena in the realm of cosmology, physics, and mathematics. Since roughly a century ago, scientists have been questioning the rate of expansion, its underlying causes, and the ultimate fate. Recent findings from the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope have proven useful, but still leave room for debate.

Astronomers have established that the universe is not only expanding, but also doing so at an accelerating pace. This is driven by a mysterious force known as dark energy, which raises key questions about the possible end state of the universe. Unlike normal or dark matter which have gravitational attraction, dark energy exerts a repulsive force that pushes galaxies apart. One theory known as the “Big Freeze” suggests that if the acceleration continues indefinitely, the galaxies will drift apart, stars will die, and the cosmos will become cold and dark. Given Occam’s razor (a rule stating the simplest explanation is most likely to be true), this theory is more widely accepted based on current observations of the universe’s expansion.

The “Big Rip” is an alternative theory where dark energy’s strength increases over time, which eventually tears apart galaxies, stars, and planets. Recently, a theoretical physicist named Paul Steinhardt suggested that dark energy might weaken over time, halting or reversing the expansion and leading to the “Big Crunch,” in which the universe collapses back into a dense state. The “Big Rip” and the “Big Crunch” are predicted to occur in a few billion years, whereas the “Big Freeze” would occur in a few trillion.

“Astronomers have established that the universe is not only expanding, but also doing so at an accelerating pace.”

A major challenge in understanding the universe’s expansion is the Hubble tension, a discrepancy between two measurements of the universe’s expansion rate (the Hubble constant). Observations of the early universe reveal a slower rate whereas measurements from the modern universe yield a faster rate. The early universe is based on studying the cosmic microwave background, or the residual radiation from the Big Bang, using the Hubble in 1929. Modern measurements with the Webb Telescope starting in 1998 have observed the standard stars (Cepheid variables) to measure distances in space aligned with Hubble’s empirical measurements that yield different theoretical calculations. The discrepancy between these two models despite the consistency of precision may just indicate gaps in the understanding of the universe’s physics, as 96% of the universe consists of dark energy and dark matter with unknown components and nature.

The early universe observations and modern measurements are based on different methods and provide equally valid but conflicting results. Scientists continue to attempt to calculate the Hubble constant by various methods, such as using gravitational waves, to establish a definite rate of universe expansion. The truth remains elusive, from the mysteries of dark energy or from flaws in current cosmological models. The lack of certainty drives science forward, and the ultimate end state of the universe and the resolution of the Hubble tension continues exploration and creative theorization.