As Tokyo prepares to host the 2020 Summer Olympic Games, the city plans to spend $25 billion to accommodate 33 sports and an estimated nine million attendees. Arenas will be filled with national pride, traditional ceremonies, and lifelong achievements — but what happens to the fame and fortune once the Olympic flame is extinguished?

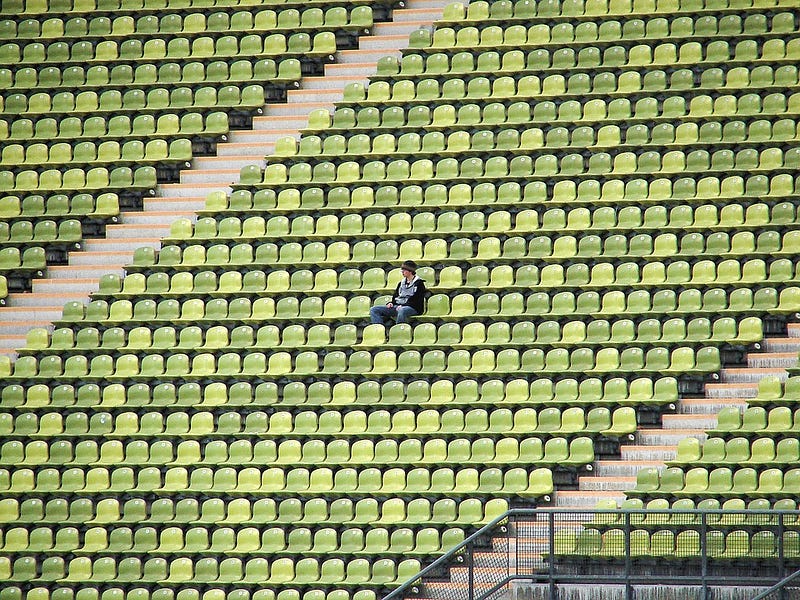

For many veteran host cities, the answer is nothing. Venues costing millions of dollars in design, construction, and maintenance are abandoned — being used just a handful of times. Economic risk, though, is only part of the problem. The process of building an Olympic city can be detrimental to the surrounding environment and community, leaving behind ravaged land and displaced citizens.

With miles upon miles of land to develop, Olympic cities take a huge toll on biodiversity. Habitats are destroyed, food sources decline, and animals are forced to find new homes; landslides and mudflows become more prevalent as well due to the absence of trees to secure soil.

The process of building an Olympic city can be detrimental to the surrounding environment and community, leaving behind ravaged land and displaced citizens.

The 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics are among the worst of Olympic past, despite their promise of a “zero waste” Games. Dr. Suren Gazaryan, a zoologist associated with the Environmental Watch of the North Caucasus (EWNC), cites incidents of illegal waste dumping, construction blocking animal migration routes, and limited drinking water access for locals.

Another Olympic tragedy occurred in Rio de Janeiro, where over 50,000 people from local communities were displaced to make room for luxurious venues. From “flash evictions” to withholding information, residents were neglected during construction and often not given proper compensation to make up for losing their homes. This caused many to move into low-income housing in suburbs with little infrastructure, “demonstrating that rather than benefit from urban improvements, those displaced suffer their impacts,” according to the Norwegian Refugee Council and International Displacement Monitoring Centre. Due to lack of funding from the Brazilian government, maintenance of the 2016 venue has been put on hold, leaving arenas to rot.

While many cities have dropped the ball on environmental and societal sustainability, some have taken proper care to avoid the downfalls of their counterparts. Cities like Sydney and London implemented green infrastructure during the games, employing free public transit and solar energy, while also planning ahead to ensure a sustainable future.

Sydney’s 2000s Olympics led to the creation of “Australia’s first large-scale urban water recycling system, which continues to save approximately 850 million litres of drinking water each year,” as reported by the Olympics website. In addition to this ongoing project, the city remodeled venues for commercial and residential use.

A little over a decade later, London’s Olympic Park was built on once-contaminated industrial land, repurposing an otherwise deteriorating landscape. What could be built as temporary was, and what could not was promised to be offset using other sustainability tactics. After the games, London has transformed its Olympic Park back to greenspace and revitalized the canals and rivers running through it.

As societies begin to value sustainability over flash, Japan is expected to act as a turning point in how the Olympics are run.

For many years, host cities were selected based on who could spend the most money to put on the most elaborate games (hence Sochi’s $51 billion bid). As societies begin to value sustainability over flash, Japan is expected to act as a turning point in how the Olympics are run. To eliminate a large portion of monetary and environmental costs, 25 preexisting structures will be utilized, leaving ten temporary and eight permanent venues to be built. Japan also promises to use native plant species in their landscaping and recycling rain and wastewater. In the coming months, it will become evident if Japan can uphold these commitments or if the Tokyo Olympic Park is destined to become yet another abandoned venue.

The Olympic Charter states “the goal of the Olympic movement is to contribute to building a peaceful and better world by educating youth through sport practiced without discrimination of any kind and in the Olympic spirit, which requires mutual understanding with a spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play.”

For the Olympics to not only speak with their words but with their actions, a conscious effort must be made to protect environments and communities across the world. This means respect and transparency with a host city’s citizens, affordable expectations for governments, and meticulous planning to guarantee minimum ecological impact before, during, and after the games. Over 100 years after the modern-day games’ conception, it is time the Olympics fully exhibit the ideals of peace and education they preach.