Stress is an inevitable part of life, but when it becomes chronic, its effects can persist far beyond mere psychological discomfort. Chronic stress is characterized by prolonged exposure to physical, emotional, or environmental stressors. Unlike acute stress, which is the body’s natural response to a threat, chronic stress persists over an extended period of time and can have profound health implications. Research has shown that chronic stress can lead to a variety of ailments, ranging from neurological disorders to cardiac problems. In fact, it is theorized that up to 90% of human diseases are related to the activation of the stress system.

There are a variety of chronic stress sources in today’s world; however, Yale Medicine’s Interdisciplinary Stress Center finds that almost all stressors cause people to feel stuck in their difficult situations. Some examples of this include poverty, a dysfunctional marriage or family, chronic illness, trauma, and more. When one encounters a stressful situation, the body initiates a cascade of physiological responses known as the stress response. The release of stress hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline, activates the sympathetic nervous system and prepares the body to confront or flee from the perceived threat. This response is crucial for survival in the short term but can cause problems when continually activated by ongoing stress. Specifically, chronic stress can lead to the complete suppression of the immune system, leaving the body especially susceptible to illness and harm.

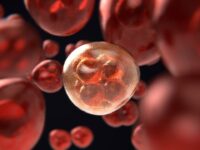

This vulnerability to the immune system, a complex network of specialized cells, tissues, and organs, acting as the body’s primary defense mechanism against pathogens, can cause humans to be continually infected with bacteria and viruses, leading to constant illness. Research on the effects of chronic stress on the immune system has grown substantially in recent decades, along with the growth of the field of “psychoneuroimmunology” founded in 1975.

Chronic stress can also contribute to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. This is due to the continual release of stress hormones such as cortisol, that stimulate immune cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are small proteins involved in cell signaling that increase inflammation throughout the body. Inflammation is necessary for fighting off bacteria and foreign invaders, but without them present, inflammation can affect healthy tissue and lead to a variety of conditions like arthritis, asthma, diabetes, and more.

A 2018 systemic review from the University of Canberra in Australia analyzed nine studies examining pro-inflammatory cytokines in participants with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The review found that all but one demonstrated a statistically significant difference in at least one pro-inflammatory marker in the PTSD group compared to the control group, with the former displaying an elevated level of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

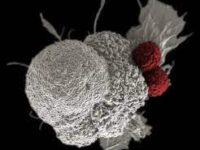

Beyond the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, stress hormones can also suppress the activity of immune cells, such as T-cells and natural killer cells, which are crucial for targeting and eliminating infected or abnormal cells. Essentially, cortisol can bind to receptors on T cells, inhibiting the production of crucial cytokines that promote T cell proliferation and activation. Similarly, cortisol binds to the same receptors on B cells, which are responsible for the production of antibodies. Antibodies are a crucial aspect of the immune system that identify harmful substances in the body.

With the inhibition of B-cell proliferation and thus antibody production, it becomes almost impossible for the immune system to identify and neutralize pathogens. This can lead to the overall suppression of the immune system, making it a lot harder to combat illnesses and stay healthy.

“With the inhibition of B-cell proliferation and thus antibody production, it becomes almost impossible for the immune system to identify and neutralize pathogens.”

In a 2016 study from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, Dr. Bonnie McGregor and her team of researchers led multiple longitudinal studies analyzing the amount of B-cells in stressed graduate students. These graduate students displayed a statistically significant reduced B-cell count compared to the control populations.

“The relationship between chronic stress and the immune system is intricate and multifaceted and as our understanding of this connection grows, so does the importance of adopting strategies to manage and alleviate chronic stress.”

Inflammation and immune cell suppression are only two effects of chronic stress on the immune system, yet their results can be detrimental to an individual’s overall health. The relationship between chronic stress and the immune system is intricate and multifaceted, and as our understanding of this connection grows, so does the importance of adopting strategies to manage and alleviate chronic stress. By addressing stressors and incorporating positive lifestyle choices, such as meditation, movement, and adequate sleep, individuals can support their immune system, fostering overall well-being and resilience in the face of life’s challenges.