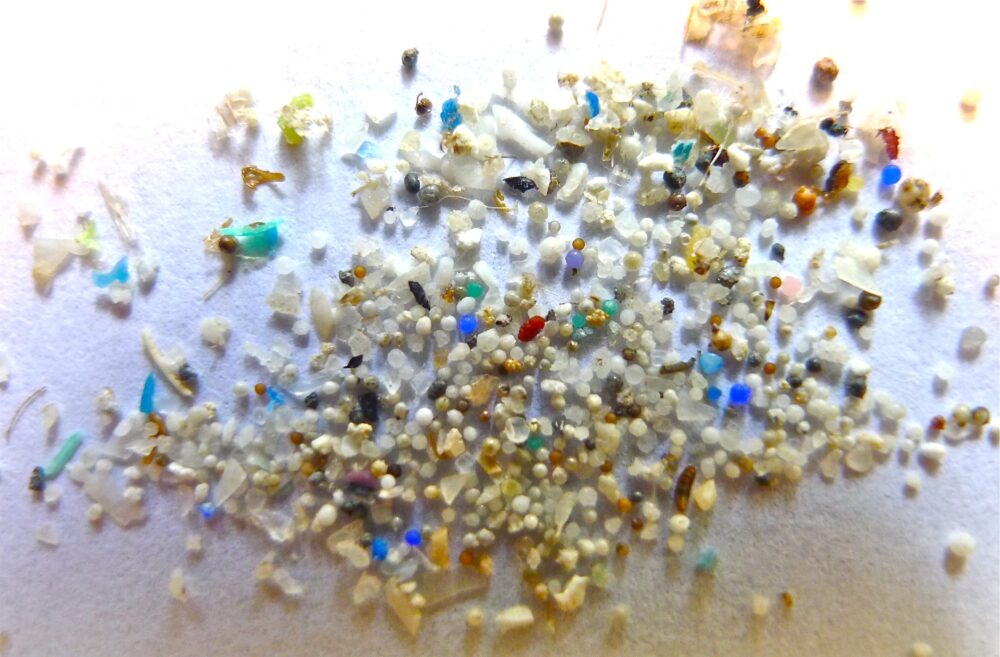

Resting in our polar ice, nanoplastics are a small force about the size of a virus silently contaminating our environment and creating potentially devastating consequences. A team of international scientists set out to measure the precise concentration of nanoplastics in polar ice cores. For the first time, there are figures on the extent to which nanoplastics have infiltrated the Earth’s southern and northernmost regions.

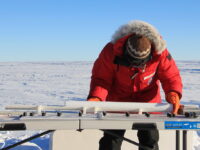

Prior to the team’s work, research showed that nanoplastics account for a large portion of plastic pollution created in the environment and displaced to remote locations. Due to a lack of technology for measuring concentrations of this minuscule plastic, it was unknown to what extent nanoplastics existed in polar regions. Thus, the scientists created a novel way to measure them using a version of mass spectrometry. They took melted ice samples, filtered them, and performed mass spectrometry. Each sample’s raw mass spectra were essentially an identifiable fingerprint. Thus, by comparison, they determined which nanoplastics were present in the ice.

Samples for this experiment were 14-meter-deep cores from two locations: a firn core from central Greenland and a sea ice core from Antarctica. The study determined that nanoplastic mass concentrations were 13.2 ng/mL in Greenland and 52.3 ng/mL in Antarctic sea ice. Polyethylene (PE), used in plastic packing film, grocery and garbage bags, wires, bottles, and toys, was a major component of the pollution, making up approximately 50 percent of the samples. Both locations, however, are highly remote. This begs the question: where did these nanoplastics come from?

Based on previous measurements of wind trajectories, it is likely that these plastics originated in North America and Asia.

In Greenland, PE made up 49 percent of the sample. Multiple modes of transportation likely moved plastic to this location. Firstly, nanoplastics travel via long-range atmospheric transport or within moving air. In addition, they may come from the sea surface, where UV radiation breaks them down. Certain acts that seem harmless, like washing clothes, can cause nanoplastic pollution in waterways. Contaminated water then reaches the sea surface surrounding the poles. This is supported by the high concentrations of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a plastic associated with the clothing industry, as well as bottle production and tire plastics. Based on previous measurements of wind trajectories, it is likely that these plastics originated in North America and Asia.

Similarly, PE contributed to more than 50 percent of the sample in Antarctica. Here, it is again likely that surface area sea water causes plastic pollutants to be incorporated into ice. In addition to PE, there were high levels of polypropylene (PP) plastics, which are used in chip bags, diapers, and food containers. Contrastingly, there was less PET and no tire plastics. In this sample, there was also a higher concentration of nanoplastics at the top and a lower concentration at the bottom. This is due to the way sea water freezes into polar ice. At the beginning of the season, surface water freezes to make columnar and granular ice. However, from July onward, ice gathers from supercooled water beneath the ice shelf, where it was protected from sea surface plastics. Thus, the concentration of nanoplastics drops deeper into the sample.

There is a mixture of ways in which nanoplastics reach polar regions. Some are transported via air, while others travel via sea water. Collectively, one thing is clear: the source of these pollutants is human-made products and habits. Whether it be overt, such as littering plastic bottles, or more hidden, such as washing highly synthetic clothes, humans are effectively starting the chain of pollution that ends with nanoplastics in our arctic poles.

Humans are effectively starting the chain of pollution that ends with nanoplastics in our arctic poles.

The team’s discovery of a method to measure nanoplastics in polar ice and the experimental determination of this concentration is highly significant in the context of our changing climate. Nanoplastics in these regions date back to the 1960s. This means that pollutants have impacted organisms that are not used to plastic in their environment for over half a century. Various studies show that nanoplastics harm organisms. For example, their toxicity to marine organisms causes impaired growth and development, larval malformation, and subcellular changes. These organisms are not the only species at risk from nanoplastics. Humans are also impacted by them, causing cell damage, inflammation, and producing reactive chemicals in the body.

This international scientist team urges further research into this subject. They believe finding the precise source of contamination is an urgent matter. It is an essential step in preserving the health of organisms that existed centuries before humans began walking — and polluting — the Earth.

Environmental Research (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112741