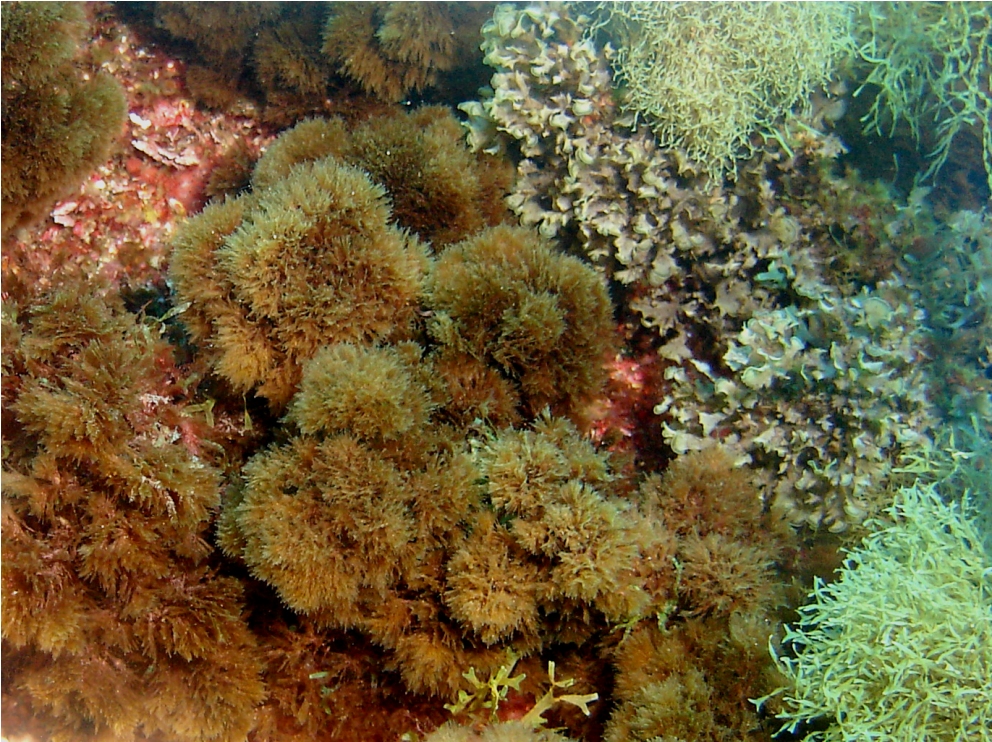

Often dismissed as slimy plants lurking beneath lakes and rivers, macrophytes may actually hold the key to the looming agricultural fertilizer crisis. Excess nutrients in water bodies, known as eutrophication, allow macrophytes to thrive. When aquatic plants die and eventually decompose, oxygen is consumed, creating anoxic conditions that can kill fish and other organisms. Eutrophication is extremely destructive to the environment, costing the US economy nearly $2.2 billion annually due to reduced property value, damaged fisheries, and loss of recreational activity. However, a new use for these slimy plants has deviated from this bleak impression. Recently, an innovative way to transform macrophytes from a mucky mess into a synthetic fertilizer alternative has emerged.

Human activity and agriculture lead to frequent loss of nutrients from soils, scattering them throughout the environment. Maintaining a closed-loop system of nutrient use is crucial, as mineral deposits are finite resources. In particular, phosphorus resources are estimated to be depleted in the next 50 to 100 years.

Macrophytes act as a nutrient sink, absorbing and storing nutrients from runoff into lakes, and could serve as a significant target for returning nutrients to the soil. When harvested, macrophyte biomass can be utilized in agriculture as an alternative to synthetic fertilizers. Further treatment prior to application is essential to eliminate the risk of pathogens and weed propagation, especially for fields where crops are grown for human consumption. This generates a product that slowly releases nutrients into the soil, reducing the risk of further nutrient loss through runoff. In addition to treatment methods, there are numerous harvesting techniques available, such as hand pulling and mechanical cutting. While macrophyte harvesting can be costly, the use of aquatic plant biomass in agriculture reduces overall harvesting costs.

“When harvested, macrophyte biomass can be utilized in agriculture as an alternative to synthetic fertilizers.”

Nutrient concentrations vary depending on when aquatic plants are harvested, nutrient concentrations vary, which impacts biomass efficiency. Michiel Verhofstad and a team of researchers at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology conducted one of the first field studies to determine suitable macrophyte harvesting frequency. In the species studied, Myriophyllum spicatum, an optimal harvesting frequency of twice per growing season was identified to maximize nutrient removal from the shallow study ponds. While researchers found that more frequent harvesting was effective for controlling eutrophication, it yielded lower nutrient loads within aquatic plant biomass, making this less effective for fertilizer production.

While macrophyte harvesting offers a sustainable alternative to synthetic fertilizer, there are several associated environmental risks. Hand pulling aquatic plants can reintroduce nutrients into the water column through sediment disturbance and lead to habitat degradation. Macrophytes play a key role in ecosystems, supporting high levels of biodiversity, so disrupting the population of these plants could have cascading effects on other organisms. Cutting macrophytes can also spread invasive plants, not only within the harvested waterbody but also on agricultural fields where treated macrophytes are spread.

Before macrophyte harvesting can be implemented on a global scale as an agricultural fertilizer, further field research is needed to determine the long-term impacts of harvesting on lake and river ecosystems. Suitable harvesting methods and frequencies depend on plant species and location, which are widely understudied. However, when facing such pressing environmental issues, it is key to remain optimistic. Looking towards nature and building a more sustainable relationship between humans and the environment can reveal solutions to some of our most urgent issues, as evidenced by the immense potential of macrophytes.

- Ecological Engineering (2017). DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.06.012

- Journal of Environmental Management (2015). DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.01.046

- Engineering in Life Sciences (2012). DOI: 10.1002/elsc.201100085

- Global Environmental Change (2009). DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.009

- Environmental Science and Technology (2008). DOI: 10.1021/es801217q