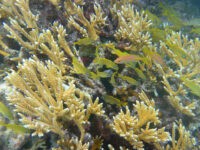

Since early expeditions to the farthest regions of the planet, scientists have been intrigued by the presence of visually similar creatures residing in both the Arctic and Antarctic. Hundreds of nearly identical worms, insects, and other small sea creatures have been discovered in both locations. These seemingly bipolar species, living at both the North and South Poles, puzzled researchers attempting to explain their similarities despite the great distance between them.

Early theories speculated that the animals had traveled across the globe thousands of years ago when global ocean temperatures were more similar to those of the polar regions. Before the early 2000s, a reliance on morphological observations, observations based on physical characteristics, prevented scientists from realizing that the bipolar species have incredibly similar DNA sequences. Separation over long periods of time typically leads to convergent evolution during which the organisms develop similar traits with different genetic sequences as a result of physical isolation. However, the lack of significant genetic differences provides evidence of continuous interaction between these animals in the modern era. In 2000, marine biologist Dr. Kate Darling identified 235 identical species between the Arctic and Antarctic, prompting marine researchers to seek new ideas about how these animals travel between poles.

Bipolar species, living at both the North and South Poles, puzzled researchers attempting to explain their similarities despite the great distance between them.

It is now widely accepted that these bipolar species move via a “conveyor belt” of currents found deep in the ocean. This process, called thermohaline circulation, is caused by high-density saltwater sinking beneath lower salinity water and results in global circulation of water as salinity changes. Due to the complexity of current patterns, it takes roughly 1,000 years to cross the globe using this system. However, this continuous travel explains how the genetic similarities between bipolar species overcome the expectation of convergent evolution since it is now known that the organisms did not experience physical separation and are able to reproduce with each other to allow their DNA to interact consistently.

This research opens the door to greater questions about the evolutionary history of species that are not confined to a particular region or land mass and whether or not more global networks of interaction are hiding within the depths of our oceans.

For further reading:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090215151619.htm

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_currents/05conveyor1.html

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090215151619.htm

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_currents/05conveyor1.html