In 2023 alone, the United States experienced 56,580 wildfires, 90% of which originated from human actions such as cigarette use and campfires. Due to the rate at which wildfires occur, a great emphasis has been noted on the environmental and physical harm imposed on humans. Skin damage and cardiovascular diseases associated with wildfires have been important topics for decades. However, in recent years, researchers have been considering the impact of wildfires on mental illness.

Mental illness affects 1 in 5 adults annually. In 2022, 59.3 million U.S. adults suffered from mental disorders. Wildfires are contributing to these trends since the particles in the air resulting from the fires are small enough to diffuse across the blood-brain barrier. This damages the neural tissue found in the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. Harm to neural tissue impairs communication between neurons which can alter behavior, thus leading to immediate or future risk of mental illnesses.

A considerable amount of research investigates the association between wildfires and mental illness in adulthood. According to the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study led by researchers at the University of Colorado, Boulder, on days in which wildfires were reported, researchers saw an increase in hospital admissions for psychiatric issues including depression, suicide, and psychiatric episodes.

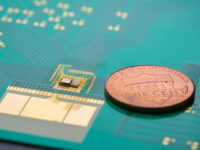

“Wildfires are contributing to these trends since the particles in the air resulting from the fires are small enough to diffuse across the blood-brain barrier. This damages the neural tissue found in the brain, spinal cord, and nerves.”

Pregnant women exposed to harmful wildfire particulate matter were studied for prenatal exposure. Years after birth, the grown subjects showed changes in brain structure, motor deficiencies, and cognitive impairments. Additionally, rodents were exposed to environments like wildfires and a neurodevelopment vital for adulthood was found to be disrupted. With the rodents and prenatal subjects, researchers focused on effects later in life; however, researchers at the University of Colorado, Boulder were interested in the influence of harmful particles on childhood mental illness.

In 2016, researchers from CU Boulder conducted a study on 10,000 youth. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers fine particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 nanometers (PM2.5) or less unsafe. The researchers tracked youth aged 9 to 11 for exposure to varying levels of PM2.5. Mental status was measured using the Child Behavioral Checklist, filled out by the subjects’ parents. Results of the study revealed a positive correlation between the number of days with PM2.5 levels exceeding the U.S. EPA standard and reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. Repeated exposure to PM2.5 showed more extreme consequences to childhood mental illness than exposure to the 2016 annual average and maximum level of 24-h PM2.5. Researchers concluded that for each day of exposure, the risk of mental illness in children increased by 0.1 on average on a scale from 1 to 50.

Continuation of research on the influence of wildfires on mental health is necessary for the development of potential solutions. Knowledge of wildfires’ indirect consequences to individual well-being may inspire the public to work harder to prevent them, leading to a healthier planet with healthier people.