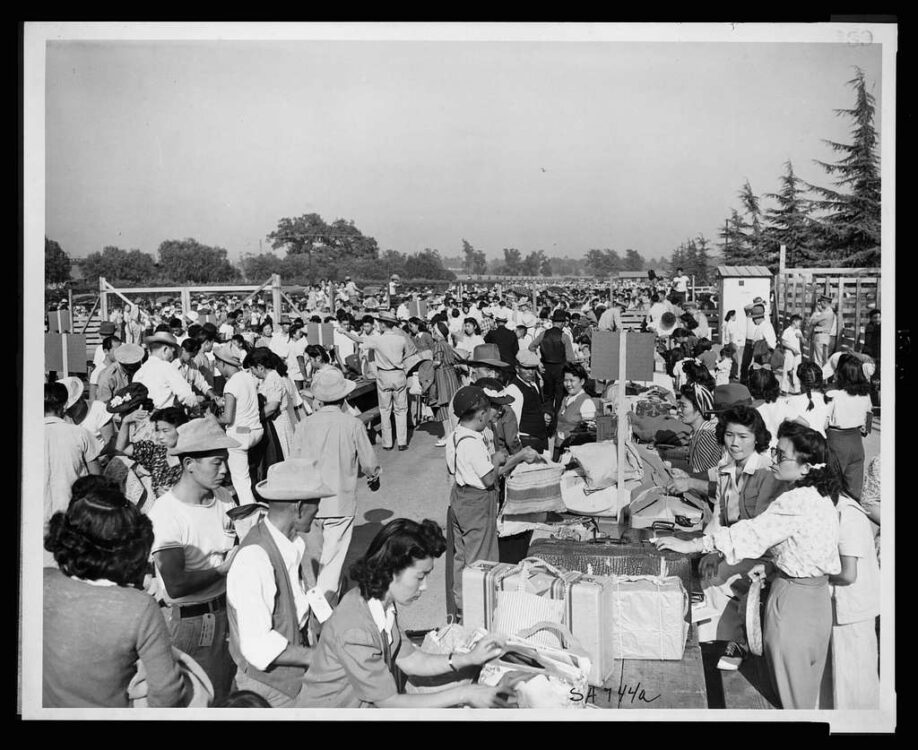

Following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, a wave of fear and distrust in all things Japanese encompassed the United States. This sentiment resulted in President Franklin Roosevelt’s issuing Executive Order 9066, which declared that all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the west coast be forcibly relocated to assembly centers and incarceration camps located in geographically isolated regions of the United States. Over 110,000 people — whether American-born or not — were handed a one-way ticket to one of 10 randomly assigned camps, allowed to bring only the possessions they could carry. They settled in outdoor camps consisting of tar and paper barracks surrounded by barbed wire and 24/7 armed patrol.

The camps had a plethora of health hazards that were intensified by harsh environmental conditions. Dust storms in the desert and disease-carrying insects in the wetlands caused a high incidence of respiratory and gastrointestinal illness. These illnesses were worsened by nutritional deficiencies from cheap government-supplied meals and contaminated water from systems built with reclaimed steel pipe from oil wells and gas lines. Passing on a communicable disease was also highly likely due to the tightly-packed living quarters.

When internees fell sick, they were sent to the scantily-built hospital found at each camp, staffed by the few white physicians and nurses who could be spared during the wartime effort, many of whom had little experience. At the Gila River camp located just south of Phoenix, Arizona, a hospital for some 10,000 internees had not been built until four months past the arrival of the first group. The medical facilities that did exist at other camps were short of proper supplies and ambulances, which meant that conditions that were typically treatable at external hospitals could quickly turn fatal in the camps.

As neglectful medical practices failed to meet the needs of the community, nurses and physicians of Japanese ancestry quickly stepped up to the plate to take control of the hospitals.

As neglectful medical practices failed to meet the needs of the community, nurses and physicians of Japanese ancestry quickly stepped up to the plate to take control of the hospitals. They built upon each other’s experience and specialized knowledge to create more effective systems to treat internee health conditions. Those with professional medical knowledge trained other internees to grow the hospital’s ability to serve the camp. Eventually, most hospitals became primarily internee-run. Dr. Benjamin Masayoshi Tanaka of the Santa Fe Camp recounts white supervisors walking in to sign the daily paperwork, then leaving for the day as Japanese staff kept everything organized.

Hospital staff took on creative measures to combat the lack of proper equipment, crafting tools with household goods and developing makeshift protocols. For example, Tanaka resorted to folding up aluminum foil to reflect back lights to see properly in the operating room. At the Tule Lake Camp in Northern California, Dr. Henry Iwao Sugiyama performed adult tonsillectomies using a tin can and a sponge. Also at Tule Lake, Dr. George Hashiba performed life-saving procedures thanks to his personal neurosurgical equipment and specialized expertise. Further stories of these courageous acts can be found in Naomi Hirahira and Gwenn Jensen’s book “Silent Scars of Healing Hands: Oral Histories of Japanese American Doctors in World War II Detention Camps.” Ultimately, the wit and ingenuity of the Japanese hospital staff saved countless internees from suffering from further illness and hardship over the following four years of incarceration.

Throughout the wartime relocation and incarceration, the Japanese community watched out for each other through spirit and health. It is the persistent strength and determination of Japanese nurses and physicians that preserved the health of the people. Friendly faces with genuine intent provided a glimpse of hope and purpose for patients in otherwise despairing situations. Their heroism has much to teach us about what it means to provide meaningful medical care and hope for the people we serve.

Journal of the National Medical Association (2011). DOI: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30317-5

Bulletin of the History of Medicine (1999). DOI: 10.1353/bhm.1999.0171