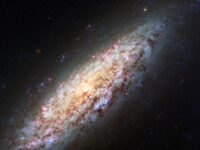

Imagine an entire city in space — a sprawling metropolis of hundreds or thousands of galaxies, each containing billions of stars, planets, and black holes. These cosmic cities are known as galaxy clusters, the largest gravitationally bound structures in the universe.

To help unravel the mysteries of these enormous entities, NU Sci spoke with Professor Jacqueline McCleary, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics at Northeastern University and an observational cosmologist who “uses galaxy clusters as a laboratory in which to explore the nature of dark matter and its interaction with galaxies.”

“A galaxy cluster is a gravitationally bound grouping of galaxies, some like the Milky Way and many that are smaller,” McCleary says.

The smallest galaxy clusters can contain hundreds of galaxies and weigh about 100 trillion times the mass of our Sun, while the largest weigh over a quadrillion solar masses and host thousands of galaxies. It would take three million years traveling at the speed of light to get from one end to the other of even the smallest cluster.

“First, protogalaxies form from the gas and star clumps of the very early universe, then these merge into galaxies. Gravity draws these galaxies into groups and then … merges into clusters. While new galaxies aren’t being created in the present-day universe, galaxy clusters continue to grow,” McCleary says.

While it’s tempting to think of galaxy clusters as giant collections of galaxies, McCleary emphasizes that galaxies make up only a fraction of a cluster’s total mass.

“Most, about 80%, of the luminous matter in galaxy clusters is actually incredibly hot gas that fills the space between the galaxies,” she notes.

This gas, known as the intracluster medium (ICM), consists primarily of ionized hydrogen and helium and is heated to over 10 million Kelvin, making it invisible to the human eye but detectable in X-ray wavelengths. Scientists rely on X-ray telescopes to reveal this hot, glowing gas in stunning detail.

Even more elusive than hot gas is dark matter, which dominates galaxy clusters.

“About 80–90% of a galaxy cluster’s mass is dark matter, which we can’t see directly… galaxy clusters were one of the first places where we got hints of dark matter’s existence,” McCleary says, referring to groundbreaking research from Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky, who in the early 20th century determined one galaxy cluster’s mass to be dominated by “dunkle Materie” or dark matter.

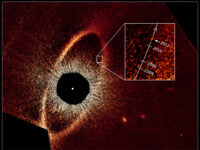

Without dark matter, galaxy clusters could not exist — the galaxies would fly apart. Observations of galaxy clusters continually inform models of dark matter today. Observing galaxy clusters requires a multi-wavelength approach, and McCleary specializes in gravitational lensing, a phenomenon where dark matter bends and distorts the light of galaxies behind it.

“Like placing a steel ball on a stretched-out rubber sheet, massive objects like galaxy clusters bend spacetime. When light from distant galaxies encounters these galaxy clusters, its path gets bent. Although the magnitude of this distortion is usually very small, by measuring light from many individual galaxies, the cluster’s projected shape and total mass can be reconstructed,” McCleary describes.

McCleary has developed software to measure galaxy shapes and colors using gravitational lensing. The end product of this research is an estimate of the total mass of a galaxy cluster and how that mass is distributed across the sky — a mass map.

“Seeing the first mass map of a galaxy cluster obtained from the stratosphere was pretty cool! It represented the fruition of years of efforts by a small and dedicated team of scientists worldwide,” recalls McCleary.

Over the next decade, McCleary anticipates significant advancements in our understanding of these galactic metropolises.

“A few big surveys coming online soon — Euclid, the Vera Rubin Observatory, and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope — will vastly increase the number of galaxy clusters we know about.” By studying the abundance and distribution of these clusters across the sky, astronomers can test their theories about the universe’s matter and how dark energy influences its expansion.

“By studying the abundance and distribution of these clusters across the sky, astronomers can test their theories about the universe’s matter and how dark energy influences its expansion.”

Galaxy clusters are not just the largest structures in the universe; they are also among the most fascinating. As our telescopes and technology improve, so too will our understanding of these cosmic cities, helping us unravel some of the universe’s deepest mysteries.