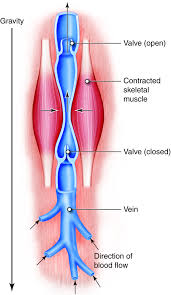

Just as roads allow for travel from point A to point B, blood vessels allow blood to travel throughout the human body, delivering the nutrients necessary to life. However, when they are blocked, they are no longer able to bring blood to all parts of the body, which is one of the leading causes of amputations. In the US alone, approximately 185,000 people in a year require amputations, with around half of those cases being due to disrupted blood vessels.

In trauma cases, disrupted blood vessels often lead to amputations, though this is avoided by utilizing blood vessel transplants. Traditionally, for patients in need of a transplant, healthy, unharmed blood vessels are sourced from another part of the body or synthetic vessels are used. Though both viable options, they have their drawbacks: it is not always possible to retrieve undamaged blood vessels from a patient, and synthetic materials carry the risk of being rejected by the body. However, in December 2024, the FDA approved a lab–grown blood vessel derived from human cells — the first of its kind to be approved for medical use.

“So, though it is initially grown from human cells, the final product is acellular, meaning the blood vessel is not alive.”

Dr. Laura Niklason and her team of researchers at her company, Humacyte, found a way to grow blood vessels from human cells, but strip the final product of any cells to make it universally accepted by patients. So, though it is initially grown from human cells, the final product is acellular, meaning the blood vessel is not alive. The idea may sound counterintuitive — growing blood vessels from human cells but making them acellular? The answer lies in extracellular matrix proteins. These proteins, which typically surround cells, are what the blood vessel is made of. Essentially, human cells are used to grow a protein blood vessel structure that lacks the actual live human cells.

Human vascular cells are used to start the process of growing the blood vessels. They are placed in controlled environments in polymer scaffolds, synthetic structures that allow the vascular cells to grow into the blood vessel shape but melt away before the final product is achieved. As the vascular cells grow around these scaffolds, they become live blood vessels, composed of the extracellular matrix proteins just like human cells. However, to make the blood vessels universally accepted by all blood types, the human cells are washed away from the final product, leaving only the matrix structure behind. When these blood vessels are transplanted into patients’ bodies, the patient’s own cells grow over the extracellular matrix protein structure, and over time, the transplanted blood vessel becomes fully integrated into the patient’s body, working as a fully functioning, live blood vessel.

Importantly, these blood vessels can be grown and stored in large quantities, making them ideal for emergency situations in which blood vessels are needed quickly to avoid amputation. These blood vessels can be stored in the refrigerator for up to 18 months and can be ready for transplant within minutes. When tested on both civilian and wartime patients, no negative effects were observed at the 30-day mark, and the durability of the transplanted blood vessels was comparable to the patient’s own blood vessels.

Though they have received FDA approval, these blood vessels are still only allowed for use in circumstances in which patients’ own blood vessels and synthetic blood vessels are not viable options for transplant. However, the phenomenon of creating a non–living structure that can become a live structure when transplanted could have broader applications in other transplant surgeries, potentially reducing the need for organ donors and providing an alternative to artificial organs.