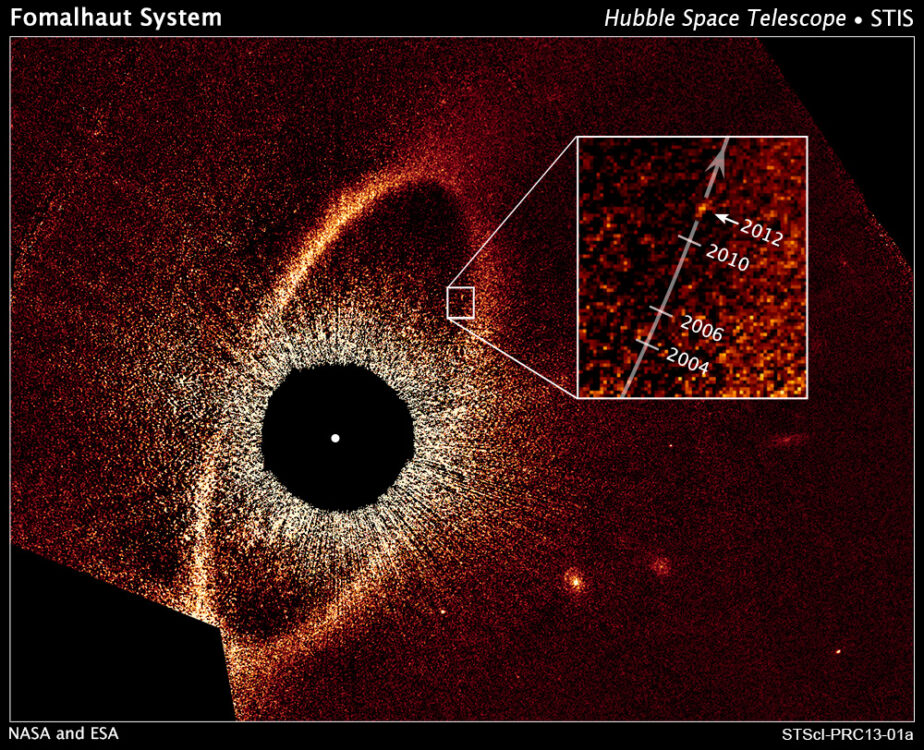

In 2008, Hubble Telescope Observations detected Fomalhaut b, an exoplanet 25 light-years away from Earth. It was one of the first directly imaged exoplanets, and was considered a benchmark in search for exoplanets. Latest research published in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) concludes that Fomalhaut is not an exoplanet at all but a cloud of dispersing dust. This explains its reducing brightness, increasing size, and failure to be detected by infrared telescopes.

NU Sci reached out to George Rieke, the co-author of the PNAS study, to understand how events unfolded with Fomalhaut b, how common such instances are in astronomy, and what it means for science in general. With Rieke’s permission, his answers are published here in full.

What is the normal procedure for detections to be confirmed as exoplanets? Was this carried out in Fomalhaut’s case back in 2008?

The risk in exoplanet imaging is that a background star projects to appear near the star you are searching for exoplanets. So you are not allowed to call the newspapers just because you found a faint object near a bright star — you have to wait patiently for a year or two. Nearby stars appear to move [in] the sky relative to distant ones because all stars are zipping through space and in different directions. Fomalhaut moves about 0.4 [arcseconds] per year, which is a lot compared with astronomical position measurements that typically have accuracy of 0.1 arcsec or better.

The discovery of Fomalhaut b was not announced until its motion in common with Fomalhaut was measured. Interestingly, the motion was not quite the same as the star, [and] was interpreted correctly as due to [the planet’s] orbital motion around the star. It should be emphasized that the discovery work was of high quality and was completely correct so far as could be told at the time.

It should be emphasized that the discovery work was of high quality and was completely correct so far as could be told at the time.

Can you think of any other instance where dust was mistaken to be an exoplanet?

No, so far as we know there is no other instance of a similar dust cloud being detected by imaging. We do know of a number of much more distant stars where we see evidence of big collisions creating massive clouds of dust similar to what we now believe happened with Fomalhaut b — these appear as an increase in the infrared brightness of the system because the new dust absorbs starlight and warms up to glow in the infrared. However these systems are some 50 times farther away than Fomalhaut, so actually imaging these events is far, far out of reach.

In your paper, you mention that Fomalhaut’s discovery was considered a benchmark in the exploration of exoplanets. Now that the exoplanet has turned out not to be so, in what way does it impact the search for exoplanets?

Fomalhaut b and the massive planets around HR 8799 were announced at the same time. The HR 8799 ones have held up very well, and an additional one beyond the three initially announced has been discovered. We have images now of exoplanets around perhaps 20 other stars, so Fomalhaut b being taken off that list does not have a big impact on the overall situation. Instead, Fomalhaut b represents a phase in planetary system evolution that we had never imaged before, so it is now a benchmark in a new direction.

Fomalhaut b represents a phase in planetary system evolution that we had never imaged before, so it is now a benchmark in a new direction.

Is it common in astronomy, in general, for discoveries to be overridden/changed by new knowledge?

Hmmm. That last question is a zinger. Of course, at some level science is all about improving and changing the interpretation of discoveries, sometimes by deeper understanding and sometimes by new observations, and often by both together. In most cases, this is a more evolutionary process — new knowledge adds to what was known before and modifies an interpretation but does not change it drastically. This is because science is actually a very conservative enterprise. There are high standards of proof for any new discovery, enforced by refereeing scientific papers to be sure that they are persuasive to other scientists.

As a result it is not common to have a discovery shown to be flat out wrong, assuming it went through this vetting process. But if we did not evolve in our understanding and change our interpretations, science would be a very boring enterprise. So I do not consider the story of Fomalhaut b to be wildly out of the ordinary, other than it deals with a change on a topic that is very high on the interest scale, both among scientists and the public.

Image source: NASA.