Debugging the gender gap in computer science: Women were the original programmers, so why aren’t they still doing it?

By Claire Bohlig, Mechanical Engineering, Computer Science Minor, 2023

Computer programming is stereotypically a male nerd field, much more than other scientific or engineering disciplines. When you picture a programmer, it is probably a geeky-looking man sitting at his computer typing away. This would be a funnier image if it wasn’t partially true. Women only hold 20 percent of jobs in computer science, and the percent of computer science degrees given to women was cut in half from 1984 to 2013, from 37 percent to 18 percent. But this disparity, and these stereotypes, weren’t always reality.

The percent of computer science degrees given to women was cut in half from 1984 to 2013, from 37 percent to 18 percent.

The very first programmer was a woman. Ada Lovelace, a British aristocrat and daughter of the famous poet Lord Byron, wrote programs for a machine named the “Analytical Engine” built for performing mathematical calculations. After studying just the schematics, Lovelace was able to write an algorithm for the engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers, a complex numerical series. Lovelace continued to write programs, papers, and notes about the Analytical Engine, and in one note she landed upon a fundamental of modern computer science. Note G explains that computers eventually should “act upon other things besides number.” Lovelace developed the concept that through abstract machine numbers, we can express powerful ideas, just as your laptop uses bits and bytes to supply you with cat memes. Sadly, the project was never funded and the Analytical Engine was never fully built.

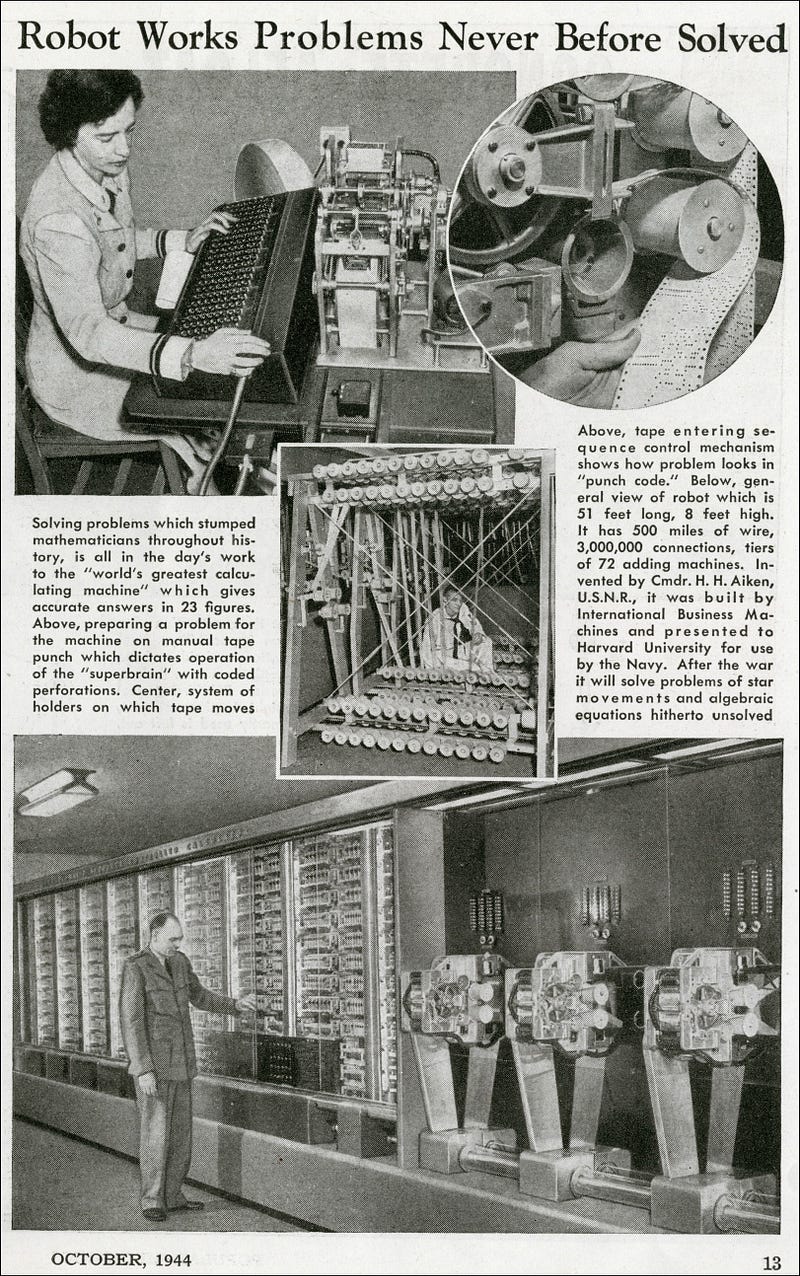

It wasn’t until the early 1940s that computing again had a focus and women were once again pivotal. During the World Wars, women were hired as workers to calculate ballistic trajectories. When done by hand, this took hours or even days, so governments across the world scrambled to find any way to calculate them quicker. Two American engineers were hired to build the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), and the female “computers” were hired to continue calculating trajectories, this time on a multi-room calculator.

These “computers” were the first modern programmers, punching holes into pieces of paper joined at the ends to create ‘loops’ that were fed into the ENIAC. “None of the girls were ever introduced [at conferences or to the press]; we were just programmers,” ENIAC programmer Kay McNulty described in the book Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computing. Men did not program the ENIAC, as they were the ones building and developing the computer, the ones doing the hard, flashy, and impressive labor.

“None of the girls were ever introduced [at conferences or to the press]; we were just programmers.”

So if the first programmer was a woman, and the idea of programming was introduced by a woman, and the original programming teams were women, what happened between then and now to cause such a disparity in the field?

Since programming was brand new, no one knew what the requirements were for being a programmer. Post World War II, businesses who wanted to use the new technology would hire anyone with a college degree and recruit for programming jobs on college campuses. But in the 1950s, only 24 percent of college graduates were women, blocking most that were interested from recruitment. Adding to that, women weren’t expected to continue in a career path. Of the programmers working on the ENIAC machine, the majority of women left the field voluntarily within two years to have children or to get married.

But the main reason for the conversion of female computers to the “bro-grammers” we see today is that programming underwent a major rebranding. A movement in the late 1960s began to market programming as “software engineering,” and since engineering was a male dominated career path, it could safely absorb the programming field under a single male associated blanket. Men became the default hire based on stereotypes alone, which was enough in a booming field to ensure the cycle of men hiring men would continue as the decades went on.

Men became the default hire based on stereotypes alone.

Today we know that men aren’t naturally better suited for engineering any more than women are naturally better suited for housework (on average the sexes perform the same on US standardized tests). And yet the number of female programmers in modern society continues to shrink.

Women were the original programmers, and had no issue developing brand new ways of thinking that are fundamentals of computer science today. With computers gaining more and more prevalence in our lives and cultures, programmers are needed more than ever. If Ada Lovelace could program a theoretical idea of a computer, women should be able to program on real computers today.