As you may have heard from loved ones who have experienced it, morning sickness is common for many women during the early stages of pregnancy, affecting approximately 70% of the pregnant population. However, a small percentage of people in early pregnancy experience a rare form of extreme morning sickness: hyperemesis gravidarum. As explained by University of Exeter’s health scientists Alice Hughes and Rachel Freathy, hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) has been found to cause dehydration, nutrient deficiencies, and weight loss in up to 3% of pregnancies. In fact, its symptoms can be so severe that the condition can escalate to hospitalization, and in some instances, maternal death.

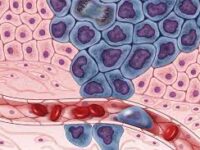

Recently, a research team at Cambridge University discovered that women with severe nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal changes had increased rates of protein GDF15 in their blood. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) protein functions in insulin secretion and regulation of cell growth and metabolism. It’s also involved in regulating the body’s response to stress, which can sometimes mean the onset of nausea and heightened sickness. While everybody is exposed to some level of GDF15 protein, it is mostly secreted by the fetus and placenta during pregnancy.

Marlena Fejzo, PhD and genetics researcher at USC, and her colleagues performed their own research on the GDF15 protein. They found a significant discovery — people with a mutated version of the Gdf15 gene have a higher risk of developing hyperemesis gravidarum than those without the variant. And, those with the GDF15 variant produce less of the protein before their pregnancy. Consequently, when exposed to the heightened amount of GDF15 during early stages of pregnancy from the fetus, the mothers bodies’ are overwhelmed and react more sensitively, causing severe nausea, dizziness, and abdominal pain.

As endocrinologist Stephen O’Rahilly put it, “the baby growing in the womb is producing a hormone at levels the mother is not used to. The more sensitive she is to this hormone, the sicker she will become.”

“‘The more sensitive she is to this hormone, the sicker she will become.’”

In attempts to further understand the role of GDF15 and how to manipulate the hormone’s effects, Fejzo and her team conducted a series of experiments on mice. They induced one set of rodents with a large dose of the protein, and the other with a smaller dose of longer acting protein. Their findings portrayed that rodents with the larger dose instantly cut back on eating, suggesting they were feeling nauseous while the long acting form of the GDF15 rodent group was not bothered as much. Their conclusion was that smaller amounts of the GDF15 protein can hinder the effect of a large dose later, as in during pregnancy.

Previous research on HG and its symptoms had been mostly attested to hormonal changes in the body such as surges in estrogen and human chorionic gonadotropin. Some even claimed morning sickness to be a “psychological cause,” misconstruing the true genetic basis of the illness even further. However, we now know that this is very far from the truth.

At the moment, researchers are studying various methods of treatment for HG — one suggests to block the Gdf15 gene and thus its hormone production to mediate the symptoms in early pregnancy. However, without discovering a safe method through extensive animal studies, determining a treatment method for HG could prove catastrophic as the effects on fetal development and conception aren’t well known at this time. Following a different direction, Fezjo and her team are currently investigating if an oral diabetes drug called metformin could be a potential treatment option. Their theory is that using the drug (which increases GDF15 in the body) prior to potential pregnancy will prepare them for the upcoming hormone surge, mediating the extreme symptoms.

In the meantime, as new gene therapies surrounding GDF15 are underway, doctors have been implementing more anti-nausea medications and intravenous fluids to aid in the “morning sickness” symptoms.