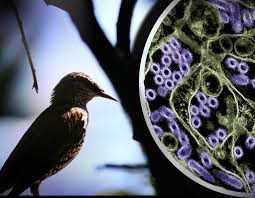

In recent years, bird flu cases have been skyrocketing. This highly infectious and deadly strain of avian influenza has not only infected thousands of poultry birds across Europe, North America, Africa and Asia, but has spread to wild birds too. The flu has even spread to mammals such as sea lions, foxes, skunks and cats.

Over 99 million wild aquatic birds, commercial poultry or backyard flocks have been affected, meaning they either died from the virus or they were culled (selectively slaughtered) to stop the virus from spreading further. A total of 400,000 wild birds were affected and 2,600 died, which is twice the reported number from the last outbreak in 2016, as written in Scientific American. Although there have only been nine reported cases of this flu in humans across the US, Ian Barr, deputy director of the World Health Organization (WHO) at the Doherty Institute in Melbourne, Australia says that these viruses are like “ticking time bombs.” Furthermore, he mentions that occasional infections do not pose a threat whereas a gradual increase in the functioning of these viruses is where the real danger lies.

The origin of bird flu is a highly pathogenic H5N1 strain that emerged in commercial geese in Asia in 1996, and spread via poultry throughout Europe and Africa in the early 2000s. By 2005, the strain had repeatedly infected wild birds in many parts of the world.. Through these spillovers, H5N1 seems to have adapted to wild birds. Bird flu has now become an “emerging wildlife disease,” according to Andy Ramey, a research wildlife geneticist at the US Geological Survey Alaska Science Center in Anchorage. In 2014, a new highly pathogenic H5 lineage called 2.3.4.4 emerged and started non-lethally infecting wild birds, creating opportunities for the virus to spread to North America. The lineage has since dominated outbreaks around the world, including current ones. According to NBC News, of the 900-plus cases of H5N1 strains in people reported globally since 1997, around half have been fatal. However, in the last two years, the global mortality rate has been lower — around 27%. Even so, those numbers largely just reflect the people who were sick enough to seek treatment. In fact, there have been more outbreaks reported in 2020 and 2021 than in the previous four years combined.

The avian flu infections are highly contagious. Infection often spreads first among wild water birds such as ducks, geese, gulls, and shore birds, such as plovers and sandpipers. The viruses are carried in their intestines and respiratory tract and shed in saliva, mucus and feces. Wild birds can easily infect domestic poultry such as chickens, turkeys, and ducks. However, not all avian flu viruses are equally harmful. For example, low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) may cause no signs of illness, or signs of mild illness like fewer eggs or ruffled feathers in domestic poultry, whereas, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) causes more severe illness and high rates of death in infected poultry. The current H5N1 virus is considered an HPAI.

Experts have found many ways to restrict the spread of bird flu. For example, monitoring of infected wild birds could help to alert poultry facilities to the risk of future outbreaks, especially in regions with large poultry and migratory bird populations that are at high risk. However, tracking diseases in wild birds is resource-intensive and challenging due to the sheer size of their populations, says Keith Hamilton, head of the department for Preparedness and Resilience at the World Organization for Animal Health. An effective vaccine for poultry could help to stem the spread, along with a decrease in the number of birds in production facilities, according to Michelle Wille, a wild-bird virologist at the University of Sydney in Australia. The poultry industry can also continue to improve biosecurity by restricting entry to facilities, protecting their water sources and decreasing contact between poultry and wild birds.

A question that arises amidst these issues is whether milk, beef, chicken and the rest of our food supply are safe. This concern is understandable as the outbreak has spread from birds to dairy cows for the first time. More alarming is that a study found fragments of bird flu DNA — which is not the same as live virus — in 20% of commercially available milk in the US. There has been no indication that bird flu found in pasteurized milk, beef, or other common foods can cause human illness. Even if live bird flu virus got into the milk supply, studies show that routine pasteurization would kill it. Initial tests did not find the virus in ground beef. Furthermore, on inquiry and tests on all dairy farms across Massachusetts, the farms are 100% free of bird flu now. On the other hand, at least 14 states across the country since March have tested positive for avian influenza, says the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture.

Another question relevant to the prevention of bird flu is, what can be done to stay safe? A simple strategy would be to maintain distance from sick or dead animals and keep pets away from them too. Avoiding animal feces is also a must. Raw or undercooked food should also not be prepared or consumed. Additionally, a question that may come to mind is, can humans get the bird flu? Yes, although it is unlikely. When flu viruses mutate, they may be able to move from their original hosts — birds in this case — to humans and other animals. This virus may be introduced into the body through the eyes, nose or mouth. For example, a person may inhale vital particles in the air (droplets, tiny, aerosolized particles, or possibly in dust) or they might touch a surface contaminated by viruses. Bird flu in humans typically causes symptoms like seasonal flu, such as fever, runny nose, and body aches.

Despite all the worrisome news about bird flu, this recent outbreak may wind up posing little threat to human health. Virus strains may mutate to spread less efficiently or to be less deadly. Efforts are underway to contain the spread of bird flu to humans. There is hope that a vaccine might be developed to protect cattle from the flu. Additionally, some birds are appearing to develop immunity against the virus, reducing the risk spreading between birds and other animals. In the rare case that human infections with bird flu did become more common, researchers are working on human vaccines against bird flu. We do not know much about this virus yet and a lot is to be discovered still, hence killing wild birds is not the right way to proceed to prevent this disease from spreading. Michelle Wille says, “the same way we shouldn’t be shooting bats because of coronavirus, the solution to this is not trying to kill wild birds.” Lastly, the ongoing threat to bird flu, particularly the H5N1 strain, underscored the need for vigilant monitoring and robust biosecurity measures. As we navigate these challenges, it is crucial to stay informed and prepared for any developments in the fight against avian influenza.