What if there was a way to track the entire record of Earth’s climate, from hundreds of thousands of years ago to the present day? Deep within the immense masses of ice comprising Earth’s most remote glaciers lie clues into the past and future of climate change. Similar to looking at the individual rings of a tree, the layers of ice that accumulated year after year capture the history of climate patterns and global events.

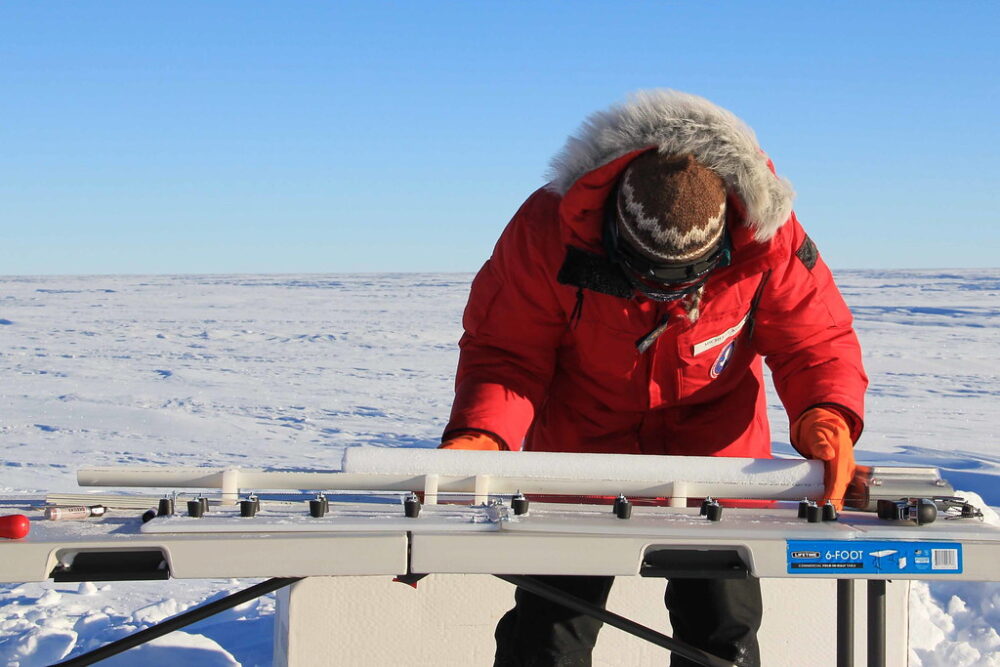

Paleontologists travel to the most remote, unexplored edges of the planet to drill deep into glaciers and collect ice cores. The process of extracting ice cores from glaciers may take up to eight weeks, drilling up to two miles in depth. To decide on an area in the glacier to drill, properties of the ice including thickness, layers, and level of flow are all tracked. This is certainly an impressive feat, as the paleontologists face Earth’s most extreme conditions with temperatures below freezing and wildlife to be wary of. Once the ice cores are successfully extracted and measured, they are packaged for transport to storage facilities. The US National Ice Core Laboratory, located in Lakewood, Colorado, is regarded as the “ice core library,” with archives from all around the world that can be sent to scientists to help them in their climate research.

Paleontologists travel to the most remote, unexplored edges of the planet to drill deep into glaciers and collect ice cores.

The characteristics of the ice cores give insight into the temperature, precipitation, wind, and atmospheric composition of a certain period of time. The layers of the ice core are distinct from one another, with the thickness and texture dependent on how much snow fell in the winter or the amount of sunlight in the summer. The snowfall of each season has different properties that are distinguished in the layers of the ice cores. The bubbles in the ice can also be analyzed to determine the relative gas concentration of the atmosphere in each layer. Additionally, by looking into the ratio of oxygen-16 and oxygen-18, the global temperature can be determined, since oxygen-16 requires colder temperatures to convert from water vapor to precipitation. The gas concentrations in the ice cores were what first revealed the link between the rising carbon dioxide levels and global temperature throughout Earth’s climate history. Within the layers of the ice cores, researchers have also found dust accumulation, which may signify the occurrence of a volcanic eruption. Samples of the ice core can also be melted down and run through different instruments to look for any traces of pollution, metal, sulfates, and aerosols. This can point to more clues about the state of the Earth at that time period and any global events that may have occurred.

The layers of the ice core are distinct from one another, with the thickness and texture dependent on how much snow fell in the winter or the amount of sunlight in the summer.

The entire process of analyzing the ice core samples requires special precautions to be taken to avoid any contamination. Paleontologists must wear special clean suits and work in an extremely sterile environment. Erich Osterberg, a professor of Earth Science at Dartmouth, emphasized the importance of this process, stating that “even just a fingerprint from a scientist holding the core can ruin the sample.”

Although the properties of each layer represent only a minuscule portion of time in the grand scheme of Earth’s history, the layers combined reveal patterns in climate change. By looking at ice cores, we now have a full history of greenhouse gases dating back to 800,000 years ago, which can be used to predict the direction that our climate may be headed. Moreover, we can narrow in on the specific conditions that may cause the climate system to change dramatically. Studying ice cores in different areas of the Earth also provides us insight into the variability of climate regionally and how that differs from the global climate. Simulating past climates based on the evidence from the ice cores can validate or invalidate the current climate models. In an age of significant climate change coinciding with the rise in greenhouse gases, studying ice cores will help us predict and, better yet, protect our future.