Across fields of academia and within everyday life, the origins of scientific knowledge are often credited to European scholars, philosophers, and schools of thought. Embryology, the study of embryonic development, has been no stranger to this pattern of Eurocentrism, with Aristotle being widely considered to have created the field of developmental biology during the fourth century BCE. Modern accounts of embryological history mention the influences of English, German, and ancient Greek thinkers, but rarely make note of the theories that emerged elsewhere, particularly within ancient communities in Mexico and Central America.

Many Mesoamerican societies held detailed knowledge of midwifery, obstetrics, and embryonic development. In Mexico, artwork created by the Olmecs showcases statues of people with 1-to-3 and 1-to-4 head-to-body proportions, which are appropriate for fetuses ranging from 12 to 30 gestational weeks. These statues display developmentally incomplete craniofacial and limb details of fetuses as well, further promoting the notion that these were intended to be interpreted as embryos.

Modern accounts of embryological history mention the influences of English, German, and ancient Greek thinkers, but rarely make note of the theories that emerged elsewhere, particularly within ancient communities in Mexico and Central America.

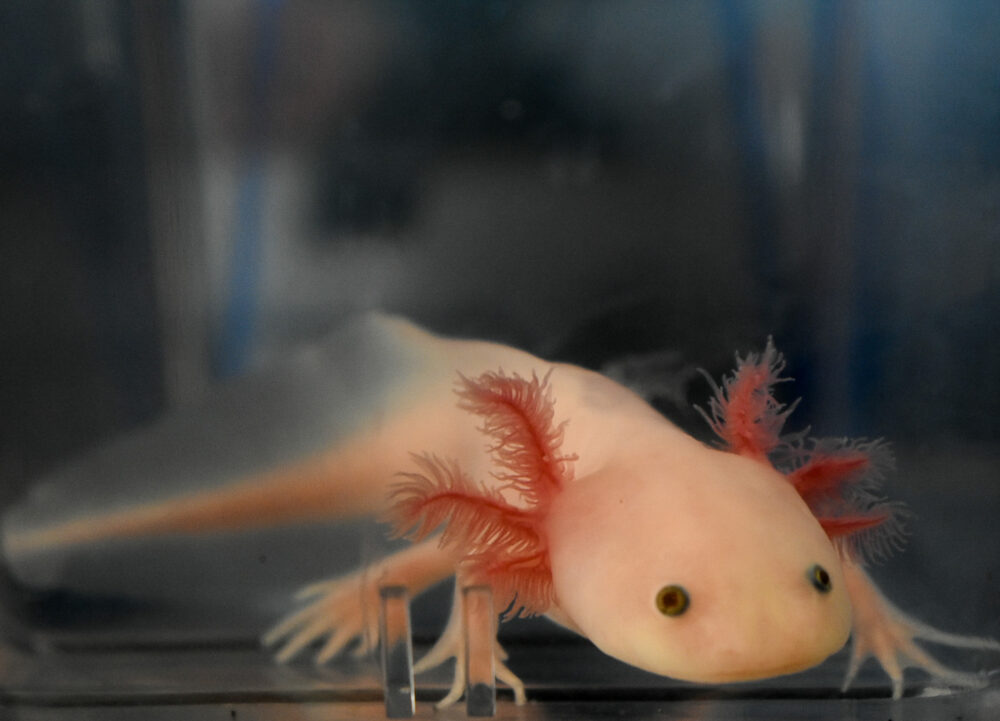

The ability of Olmec artists to create artwork following the pathway of fetal development is believed to be influenced by the presence of axolotls in Central America. Axolotls, a salamander that served as an important food source for the Olmecs, have large embryos that are easily visible throughout the period of embryonic development. Since many Olmec fetal sculptures resemble axolotl embryos with more humanoid faces, it is highly probable that these artists were able to observe the axolotls’ development and conjecture that humans followed a similar sequence. Visually tracking embryonic stages of an organism was an opportunity that many early European embryologists did not have. Consequently, the realization that humans are primarily similar to many other animals was another major facet of early Mesoamerican embryology that European branches lacked.

Since many Olmec fetal sculptures resemble axolotl embryos with more humanoid faces, it is highly probable that these artists were able to observe the axolotls’ development and conjecture that humans followed a similar sequence.

Early medical journals from Oaxaca recorded a case of human conjoined twins that occurred in 1741. These journals also contained previous research about conjoined calves and chickens that was compiled alongside the human case to determine how the children may have developed. Between 1775 and 1800, medical publications throughout Mexico and Guatemala documented more than 50 cases of birth abnormalities that were compared to similar cases in animals to better understand the patients’ conditions. Comparing newborns with congenital abnormalities to other natural beings stands in stark contrast to the mystique surrounding disability that was present in European “freak shows.” This allowed for research of these conditions with less stigma than in European embryological spheres.

Though European thought has dominated modern developmental biology and embryology, consideration of the research and mindsets of other cultures may result in a multi-dimensional perspective on how best to use knowledge of embryonic development across species to respond to human development.

Development (2021). DOI: 10.1242/dev.192062