One thing science does very well is teach us how little control we have over the universe — this includes our own thoughts and behaviors. We might be the masters of our fates, but we cannot change the machinery in our bodies that has been meticulously designed over thousands of generations of Homo sapiens. When it comes to nature versus nurture, one behavior that has always been totally attributed to nurture — the environment one is raised in — is our first language. This long-held belief is what makes a study published in May 2020 so remarkable: it has provided evidence to support that the language one speaks is linked to their genetic code.

Understanding the biological basis of language presents a “Which came first: the chicken or the egg?” conundrum. A Hindi speaker’s neurons might fire a little differently than those of an Arabic speaker, but is that because of biological differences that have existed since birth? Or, have their life experiences shaped their neural connections differently?

“They tried to connect the dots between the specific genes, the people who expressed them, and the languages they spoke.”

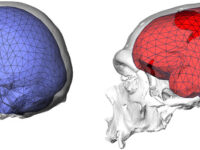

When it comes to genetics, however, things are more straightforward because life experiences cannot change the code itself. In 2007, two scientists from the University of Edinburgh did a statistical analysis on 983 genes from the genomes of people from 49 different populations around the world. They tried to connect the dots between the specific genes, the people who expressed them, and the languages they spoke. Ultimately, they found significant correlations between people who spoke tone languages and had particular versions (alleles) of the genes Aspm and Mcph.

A tone language is one that uses pitch to elucidate a word’s meaning. English speakers use tone to indicate the meaning of sentences (like raising the pitch of one’s voice at the end of a sentence to indicate a question) but not individual words, so it is not a tone language. Tone languages make up about half of the world’s 7,111 languages and are most spoken in Central Africa and Asia. The specific alleles of Aspm and Mcph that the 2007 study homed in on happen to be most concentrated in people from these areas.

Excited by this finding, the researchers proposed the genetic-biasing hypothesis of language evolution: certain alleles of genes can affect language evolution by predisposing its carriers to use certain linguistic features (e.g. proportion of vowels to consonants, subject-verb order, or tone) in their speech. The idea is that these features are first used in speech inadvertently, then shared among members of the same community and through generations, eventually getting preserved in the modern version of the ethnic group’s language. Now, 13 years later, we have the first direct evidence to support this fascinating hypothesis.

Professor Patrick Chun Man Wong and his colleagues from the Chinese University of Hong Kong came together from six different departments to design and perform an experiment to test the link between nine alleles from three different genes and speakers of Cantonese (a tone language). The researchers genotyped 426 native Cantonese speakers, surveyed them about their life experiences and measured their lexical tone perception. This test involved playing the same syllable for the participant in three pitches. In a series of 204 trials, the participant had to identify whether the third syllable had the same pitch as either the first, the second, or neither prior syllable.

The researchers found that, on average, people with the TT allele of the Aspm gene performed 3.69 percent better on the lexical tone perception test than those who did not (a statistically significant difference). In the statistical analyses they performed to isolate the influence of genetics, the researchers removed the possible influence of confounding variables, so this increase in lexical tone perception is purely due to the allele. Interestingly, using survey data, the scientists also found that people without the TT allele can match the performance of those with it on the lexical tone perception test if they have had musical training. So not only is this study important for the scientific community, but it points to musical training as a possible early intervention for children who have communication disorders and speak tone languages.

Considering current globalization and immigration trends, many fewer people today speak the same language as their ancestors. But even if we don’t share any experiences with our ancestors, we know we share their DNA. Those enigmatic strands of molecules know us best — perhaps even the secrets to our inner universes.

National Academy of Sciences (2007). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0610848104

American Association for the Advancement of Science (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aba5090