Claiming the lives of famous senators such as Ted Kennedy and John McCain, amongst many others, glioblastoma is one of the most aggressive and fast-growing brain tumors. With a median survival rate of just 14 months after diagnosis, glioblastoma is known to be extremely treatment-resistant and highly malignant.

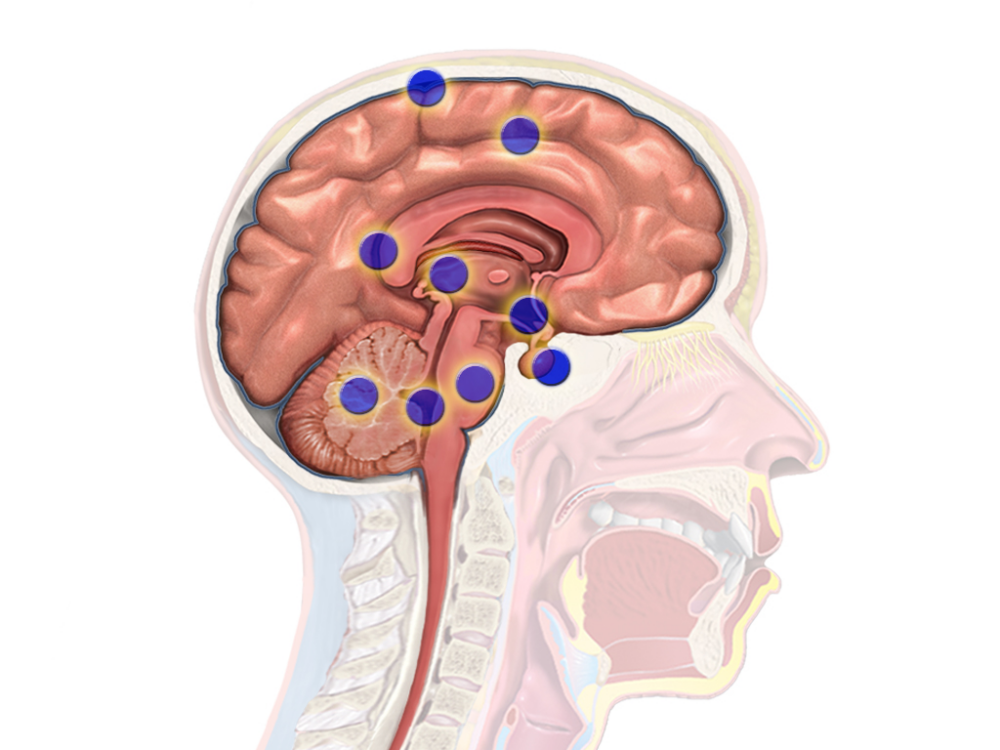

Glioblastoma begins from glial cells, which surround neurons to support and protect them. These cancerous cells are then able to access deeper portions of the brain by following blood vessels and white matter tracts, limiting options for surgical resection. Additionally, glioblastomas model a positive feedback loop during which cancerous cells secrete their own neurotransmitters, increasing hyperactivity in the area surrounding the tumor and further progressing cancer growth.

Dr. Shawn Hervey-Jumper, a notable neurosurgeon at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), has studied the hyperactive positive feedback loop within gliomas. His research team at UCSF conducted a study with patients suffering from glioblastoma in speech-associated regions of the brain. When asked to name a series of pictures, patients with glioblastoma showed activation in more regions of their brain, compared to control groups. This suggests that the brain may recruit broader neural networks to compensate for tumor-related damages to speech areas while remodeling the brain.

Hervey-Jumper equates this interaction to an orchestra: “If you lose the cellos and the woodwinds, the remaining players just can’t carry the piece the way they could otherwise.”

“The idea that there’s conversation between cancer cells and healthy brain cells is something of a paradigm shift.”

Likewise, when glioblastoma damages parts of the brain or renders them unable to carry out their functions, the brain must adapt by using other localized parts of the brain. However, as in the orchestral analogy, it is still difficult to restore the original functions.

As the tumor cells begin to invade neighboring areas of the brain, the cells begin secreting thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), which is related to tumor development and has been correlated to increased grades of glioma. TSP-1 is a protein found in the extracellular matrix of the cell environment and regulates functions such as cell–cell adhesion and migration. Saritha Krishna, a professor at UCSF, conducted a study assessing the effects of pharmacological inhibition of TSP-1 through the use of gabapentin, a common anti-seizure drug. After treating affected mice with patient-derived xenografts with gabapentin, Krishna discovered that treated mice exhibited a decrease in tumor proliferation compared to vehicle-treated controls. In high-grade gliomas, tumor cells show interactions with nearby neurons, driving glioma growth and neuronal excitability. With gabapentin, this excitability that led to growth was suppressed, therefore suppressing tumor growth rate. This trial is still in the early stages, and Hervey-Jumper suggests that “the idea that there’s conversation between cancer cells and healthy brain cells is something of a paradigm shift.”

UT Southwestern Medical Center predicts that globally 300,000 cases of glioblastoma will be diagnosed this year, and many patients will be part of clinical trials, contributing to the next breakthroughs in treatments. Due to the aggressive nature of glioblastoma, some may not live to see the full impact of the research they have contributed to. Yet each patient brings us closer to finding a cure and creates a future where glioblastoma is no longer a deadly, incurable disease. To honor them is to remember their bravery and carry their fight forward — by funding the research, supporting science, and pushing the boundaries of medicine.