Caught in the dreary cold of winter, many find themselves yearning for the long, hot days of summer, where spending time outside doesn’t come at the cost of wind-bitten cheeks and runny noses. And yet, the heat that some crave may come at a hidden price of its own. According to several studies published in 2024, prolonged exposure to high temperatures can accelerate molecular aging, and as a result, lead to a slew of adverse health effects.

Typically, aging is thought of as being an observable process, one that follows a series of changes as a person gets older — for example, wrinkles and grey hair, or a progressive loss of motor function. Molecular aging, on the other hand, is hidden and caused by a multitude of factors, the most prominent of which may be DNA damage. Though cells are typically able to repair or remove any accumulated damage, their ability to do so decreases over time, especially as an individual gets older. Consequently, cells that accumulate high levels of damage may then undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death) or cellular senescence (when cells can no longer divide but aren’t properly removed and broken down). Both processes are associated with certain types of cancers, as well as age-related disorders, making older adults particularly vulnerable to any significant changes in the molecular aging process.

Dr. Eunyong Choi, who co-authored a study that analyzed the DNA markers of over 3000 American adults above the age of 50, voiced similar concerns in an interview with Nature. Her work focused primarily on age-related changes at the epigenetic level to understand how exposure to high temperatures and heat-index values could impact an individual’s molecular age. The results suggested that people living in areas that experienced more hot-weather days were significantly older at the molecular level, aging up to 0.6% faster than those who resided in areas that experienced more cold-weather days.

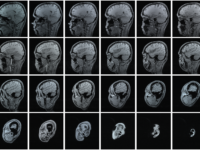

Other researchers worldwide have reported similar findings. A team of scientists from Taiwan examined DNA methylation in adults between 30 and 70 years old, comparing it to their actual age in years. Like Dr. Choi’s study, their findings indicated that age acceleration had a positive correlation with high temperature and humidity values. University of California-Irvine researchers also utilized mice models to look for genes in the brain and liver affected by heat-stress. They noted considerable liver damage in the heat-exposed elderly mice population they observed.

In all three studies, the authors emphasized that the link between heat exposure and molecular aging had predominantly negative effects. This is particularly concerning as global temperatures continue to rise, with a recent report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) indicating that 2015 through 2024 have been the “ten warmest years on record.”

Yet, efforts are already underway to address the issue. Besides working to raise awareness around the dangers of climate change, scientists are also hoping to find ways to protect or even “reverse” the negative effects of molecular aging through heat shock proteins (HSPs). These proteins serve as “molecular chaperones” as they protect severely damaged proteins from degradation. While HSPs may decline in efficiency over time, especially with higher and longer sustained heat exposure, pharmaceutical interventions can stimulate the production of these proteins to counteract the accelerated aging effects of rising global temperatures. Future research also seeks to identify, and utilize, similar proteins and other macromolecules that could mitigate heat-induced molecular damage.