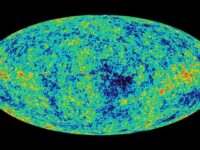

How did we get here? This question is not just an existential dilemma, but a driving force behind the life’s work of particle physicists. 13.8 billion years ago, the Big Bang occurred. In a matter of milliseconds, all the matter that would create our universe and life as we know it was formed. However, this matter did not come into existence alone. Its physical opposite, antimatter, was formed as well. If antimatter and matter existed in the same quantities, their opposing qualities, such as charge and spin, would cause the particles to annihilate each other, leaving us with what we started: nothing. Yet, here we are billions of years later — how?

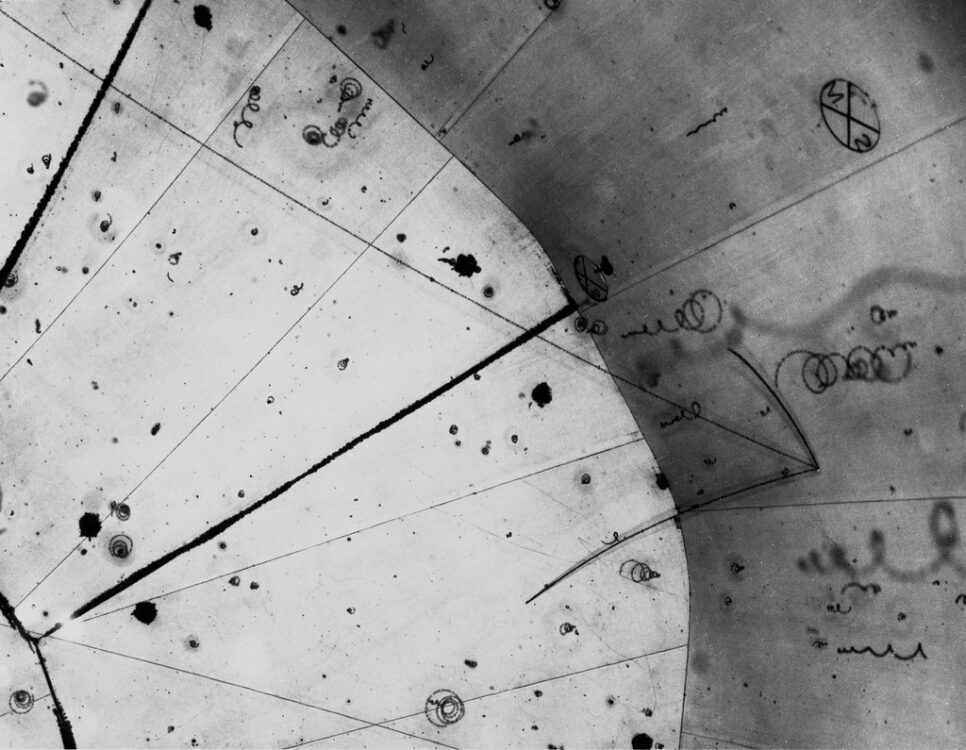

The answer to our existence might lie within a tiny, invisible, and extremely evasive particle called the neutrino. It was observed that when an atom split apart, the two resulting fragments moved apart at strange angles. In 1930, physicist Wolfgang Pauli proposed that the reason the data made no sense was because the split produced not two, but three fragments: two atomic particles with smaller nuclei than the original atom and a third, tinier particle that he called the neutrino. Decades later, the existence of neutrinos was confirmed, and it is known that billions of them pass through each cubic centimeter of this planet per second, yet they remain the least studied particle in physics. Not even their mass is known. Neutrinos are unique because, unlike all other forms of matter that have some unchangeable properties, observation has shown that neutrinos can easily shift between the three states they exist in.

“The answer to our existence might lie within a tiny, invisible, and extremely evasive particle called the neutrino.”

The shifty nature of these particles has been proposed as the reason behind the surplus of matter produced from the Big Bang. Most particles of matter interact with their antimatter counterparts in perfect symmetry, but shape-shifting neutrinos might not be perfectly symmetrical with antineutrinos; therefore, they might not be fully annihilated upon colliding.

The cosmic mystery of neutrinos and their role in the Big Bang currently remains unsolved, but recently, teams of physicists have been coming together around the world to build experiments that might finally return some answers. One experiment is the aptly named Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), which aims to study the behavior of neutrinos over long distances, located roughly one mile under the South Dakota Black Hills. The caverns, once excavated by miners searching for gold, are now home to the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), where they are constructing a multi-billion dollar neutrino receiver, scheduled to be completed in 2025.

The neutrinos themselves will begin their journey at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory near Chicago and travel across three states of bedrock to South Dakota, where they can interact with liquid argon atoms. Since neutrinos are so small and move at extremely high speeds, the chances of a collision are very rare, so an enormous amount — metric tons — of super-cooled argon is needed to collide with the neutrinos. The extremely rare collision will generate photons and electrical energy that would be detected by DUNE’s highly sensitive instruments, and the data would be analyzed to understand the movement of neutrinos. The project’s scale makes it the largest underground science-engineering project in America’s history.

The United States is not the only country seeking answers. Japan’s own neutrino experiment, Super-Kamioka Neutrino Detection Experiment (Super-K), is underway near the city of Hide, collecting neutrino data from supernova explosions across the galaxy. The latest iteration, Hyper-K, is set to start collecting data in 2027. Notably, this observatory in Japan was where researchers first discovered the shape-shifting behavior of neutrinos. In China, the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO) outside of Kaiping is scheduled to start collecting neutrino data from nearby nuclear power stations by the end of 2024.

Each team is diligently headed toward answers, but it will take years before enough data is gathered to learn anything conclusive about neutrinos. That fact has not discouraged researchers, and with rapidly advancing technology and an unwavering dedication to finding the truth, it is only a matter of time before we cross this frontier of particle physics. We have pondered the existence of humanity for hundreds of thousands of years. What is a few decades more for answers?

“We have pondered the existence of humanity for hundreds of thousands of years. What is a few decades more for answers?”