After the revolutionary discovery of antibiotics in 1910, bacterial infections — once the leading cause of human mortality — became readily preventable, contributing to a 23-year rise in average lifespan. Although traditional antibiotics like amoxicillin and doxycycline continue to save millions, decades of overprescription are catalyzing the rise of deadly new pathogens. Prolonged exposure to these toxic drugs has placed immense stress on infectious bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, permitting only the most resilient individuals to survive and pass down their advantageous genes. Today, the evolved offspring of these pathogens, dubbed “superbugs,” have achieved a global presence and possess resistance to an increasing number of drugs. As a result, infections caused by them are exceptionally dangerous — particularly in developing nations where human–animal interactions occur at high frequency and advanced medical care is difficult to find. If no new treatments are found, yearly deaths due to superbugs are projected to rise with cases disproportionately affecting underdeveloped communities. In light of this, finding new antibiotics has become a major focus of current medical research.

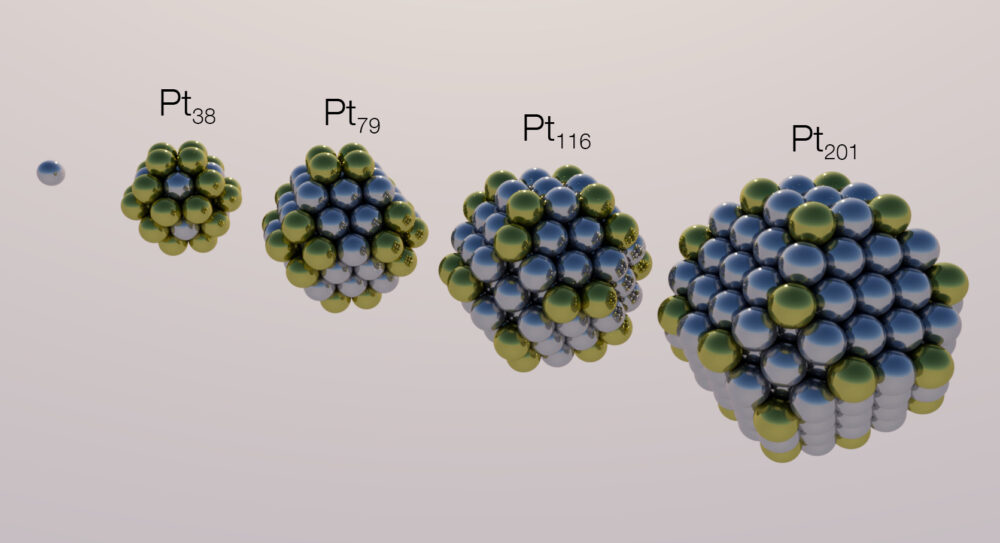

One new class of antimicrobials trending in recent studies is metal nanoparticles (MNPs). These nano-sized complexes of metal atoms are even smaller than viruses, effectively combining modern nanotechnology with the centuries–old knowledge that some metals naturally halt bacterial growth.

“If no new treatments are found, yearly deaths due to superbugs are projected to rise with cases disproportionately affecting underdeveloped communities.”

Current research demonstrates that MNPs are effective against many bacterial species, including dangerous superbugs. Today, few MNP-based products are FDA-approved, but proposals for MNP-based products span surface disinfectants and materials for infection-resistant implants and prosthetics. But how can such small pieces of metal fight the most dangerous pathogens? Microbiologists don’t fully understand the inner workings of their bactericidal activity yet, but the answer probably has to do with the fascinating, complex chemistry of metals.

Metal particles can facilitate a broad range of reactions dependent on numerous factors, such as elemental composition, surface area, and charge. As these factors vary greatly depending on the synthesis method, each unique MNP likely produces many reactions targeting different cell structures. The most widely researched reactions involve the ability of metals to form toxic, oxygen-rich chemicals called reactive oxygen species (ROS) after they enter cells. While ROS at high concentrations are dangerous to humans and pose neurodegenerative and carcinogenic effects, preliminary trials demonstrate that MNPs produce ROS on scales only toxic to bacteria, which lack many of the detoxification pathways human cells have. Primarily, this toxicity stems from an ROS molecule’s proficiency at “stealing” electrons from the bonds holding organic molecules together. Destruction of sensitive bonds in bacteria results in deadly effects such as blasting holes in cell walls, tearing apart membranes, and dismantling DNA.

Furthermore, MNPs likely release metal ions (charged atoms) as they naturally degrade. These cause further damage to harmful pathogens by seeping into enzymes vital to development and jamming them like paper stuck in a printer. While these proposed mechanisms are diverse, they are all nonspecific — meaning they target many different classes of molecules simultaneously. This nonspecific activity may be the reason behind the success of MNPs against superbugs in recent studies. Think of it like vacuuming a carpet containing dust balls of many shapes and sizes. There’s a high chance you’ll “miss a spot” and leave a clump of particularly stubborn dust behind if you do a simple once–over. But if you vacuum the carpet multiple times, each time at separate angles, the chances of randomly missing one become minimal. This multidirectional approach is incredibly important, as it resolves a key flaw of traditional drugs contributing to antibiotic resistance: their inability to address variety in rapidly evolving bacterial populations.

Recently, an international collaboration demonstrated this multidirectional approach by showing MNPs were highly effective against resistant Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus — pathogens infamous for causing foodborne illness and open wound infections. Moreover, dosages containing combinations of MNP types (i.e., different metals capable of facilitating different reactions) increased effectiveness in killing superbugs by over 90%. Findings like these have encouraged researchers to investigate as many metals as possible for antibiotic activity, with the hope of expanding their arsenal to remain on top in the arms race against superbug evolution.

In the past few years, several metals have become strong contenders for future nanoparticle drugs. Silver nanoparticles are the most popular among them, having demonstrated antibiotic activity against an extensive list of pathogens. They appear to be more lethal against superbugs than most other known MNPs, likely due to their high efficiency in generating ROS and inhibiting enzymes. However, silver ions are also toxic to human cells at moderate to high concentrations, and particle synthesis is expensive and often produces hazardous byproducts. Yet, some researchers argue these downsides are negligible. Due to their efficiency, silver nanoparticles likely require small, nontoxic doses, and research on environmentally friendly synthesis methods is an active area of study showing great promise.

Second to silver, gold nanoparticles have also been widely covered. They demonstrate effectiveness against superbugs and have low human toxicity while using similar mechanisms as silver. However, they are costly to manufacture and are often less proficient than silver. Nevertheless, they remain promising in cases requiring non-potent dosages. For example, silver MNPs alloyed with gold can maintain high efficiency while reducing overall toxicity.

Two other contenders include copper and zinc. Although copper and zinc particles can be toxic when synthesized inorganically, organically synthesized particles show potential. Some microbes naturally break down raw copper and zinc into small, bio-modified nanoparticles within the effective size range for antibiotics. Preliminary research on these particles demonstrates they may be safer and more effective than their inorganic counterparts, rivaling silver. While other MNPs (including gold and silver) can also be organically produced, copper and zinc are cost–effective to source in bulk. This makes them promising for underdeveloped communities that desperately need new, low–cost antimicrobials.

Overall, MNPs offer potential new tools in the battle against superbugs. Although safe concentrations have yet to be consistently reported and studies on animal models remain underrepresented, few traditional drugs compare to MNPs in their effectiveness against resistant bacteria. Researchers across the globe are working to address these lingering questions and deliver life-saving antimicrobials in the face of a crisis. Thanks to their efforts, a new antibiotic revolution may be on the horizon — one where unconventional metals may become frontrunners.

“Thanks to their efforts, a new antibiotic revolution may be on the horizon — one where unconventional metals may become frontrunners.”

- Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s00253-024-13050-4

- Biomedical Microdevices (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s10544-023-00686-8

- BMC Research Notes (2024). DOI: 10.1186/s13104-023-06402-2

- Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-53782-x

- ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acsami.3c00144

- British Journal of Biomedical Science (2023). DOI: 10.3389/bjbs.2023.11387

- International Journal of Molecular Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.3390/ijms24129998

- Nature Microbiology (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-022-01124-w

- Nanomaterials (2020). DOI: 10.3390/nano10020292

- Frontiers in Physiology (2018). DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00477

- Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews (2010). DOI: 10.1128/mmbr.00016-10